San Francisco’s Haymarket: A Redemptive Tale of Class Struggle

Historical Essay

by Richard Walker

| San Francisco had its own Haymarket Affair, the Preparedness Day bombing and trials of 1916-17, to compare with Chicago’s notorious events of thirty years earlier. But the circumstances leading up to and following after the convictions of Tom Mooney and Warren Billings were markedly different from those in Chicago in the 1880s and 90s. San Francisco’s working class fought pitched battles with employers several times, holding the bourgeoisie at bay again and again. Unions succeeded in creating a Closed Shop town in the years before the First World War and again in the aftermath of the General Strike of 1934. They also gained a measure of political power through the Union Labor Party between 1900 and 1910, and forced their way back to a place at the table in city government in the 1930s and beyond. All in all, the Preparedness Day bombings did not lead to the same class lynching as it did in Chicago, nor the same degree of bourgeois revanchism. |

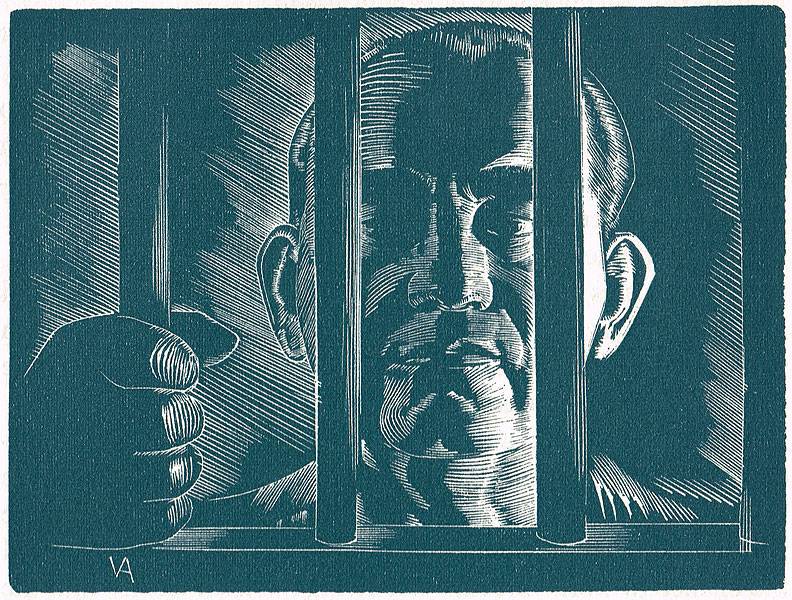

Tom Mooney behind bars.

Lithograph by Victor Arnautoff

Depression-era marchers demanding a 30-hour week and that Tom Mooney be freed.

Photo: Provenance Unknown

The Haymarket affair of 1886-87 is a dark chapter in Chicago’s history. Reading up again on the Haymarket massacre and the judicial lynchings that followed, I was struck by how brutal things were for the working class in Chicago in the 1880s, and it didn’t get any better with the suppression of the Pullman strike of 1894 (Green, 2006). The politics of class conflict at the time were thoroughly repressive, with continual provocation by the capitalists and lots of police thuggery. Remembering Haymarket takes the gloss off Chicago’s brilliant achievements of that era, such as the revolutionary skyscrapers of the 1880s, the World’s Fair of 1893, and the Burnham plan of 1908.

Chicago at the time of Haymarket was a pivotal American city in many ways. In Chicago, the dynamic relations of local, national and global scales were made manifest. Nineteenth-century Chicago rocketed to the forefront of American industrialization, sucking in hundreds of thousands of European immigrants , and was widely considered the “shock city” of the age (Miller, 1996). Chicago’s place at the apex of the resource empire of the Midwest is legend (Cronon, 1991), as is its role as the hub of the U.S. railroad network (Stover, 1997). So is its place at the vanguard of modern building, architectural design, and city planning (Hines, 1979; Bluestone, 1991).

Unfortunately, the city’s violent reaction after Haymarket was equally a beacon for the national bourgeoisie, as in the case of Andrew Carnegie’s brutal assault on the steel workers of Homestead, Pennsylvania in 1892. Conversely, the Haymarket affair burned bright in popular memory — even though it is little marked in Chicago itself (a nice bit of collective amnesia on the part of the city fathers) – and Haymarket became a rallying cry for workers and the Left around the world for the next half-century.

The reverberations of Haymarket across the landscape of industrial capitalism must seem to labor geographers to be redolent of the kinds of far- reaching connections forged among activists in the present era of globalism (Herod, 2001; Waterman & Wills, 2001). It should remind us, as well, of what one can expect in the way of containment of and control over the working class, union organizing, and radical dissent in the rapid industrialization now taking place in the rest of the world, from Turkey to China. There ought not be any naiveté about leaps to liberal democracy and respect for human rights with the transitions to capitalism going on across the globe (Walker & Buck 2007).

Chicago’s vanguard role in capitalist development does not mean that its labor history was simply repeated elsewhere; place matters in the trajectory of class struggle, as in all human affairs (cf. Massey, 2005). The simple admonition to pay attention to geographical difference is not terribly earth-shaking, of course. The problem for geographers and urban historians is to show why places have gone separate ways, despite strong commonalities within national formations like the

United States or across capitalist economies. Place matters, but how, and how much? To answer that we need more than just good local histories and geographies, or sweeping national surveys; we need comparative approaches that seek to tease out the sources of variation among cities. There are too few of those. For all its analytic power, David Harvey’s Urbanization of Capital (1985), for example, tends to flatten the urban system into units competing for capital investment (Harvey, 2003, does not commit the same mistake). For all his devotion to spatiality in Post-Modern Geographies, Ed Soja goes on to treat Los Angeles as the prototype of a new urbanism, rather than as the peculiar place that it is (cf. Davis, 1990). Students of urban landscape have been more careful about the specificities of cities, as in the works of Mona Domosh (1997) and Paul Groth (1994). We need the same kind of close reading of labor, class and political history of cities.

For that reason, I think it worthwhile to use this opportunity to reflect on the labor history of my city, San Francisco, in comparison to that of Chicago. The trajectory of class struggle in the two places played out rather differently over the late 19th and early 20th centuries. San Francisco’s working class was considerably more successful in resisting the onslaught of the American bourgeoisie from the Gilded Age to the McCarthy Era. This is not only interesting as labor history, but had ongoing significance for city politics, which veered well to the left of Chicago and the American mainstream — where it remains to this day (DeLeon, 1992; Walker, 1998). Moreover, this local history holds some useful lessons that still resonate across geographies: the role of class militancy and solidarity (on both sides); the place of labor politics beyond the unions; the significance of racism and whiteness in class formation; and the impact of cumulative victories for popular struggle. In all these regards, San Francisco’s workers followed much the opposite course of American labor nationwide and its long postwar decline, as outlined so disconsolately by Mike Davis (1986).

Of course, San Francisco was a different kind of city than Chicago in many regards – smaller, less industrial, more isolated, facing the Pacific. But, as another of the United States’ pivotal cities of the 19th and early 20th centuries, it shared many of the same scalar characteristics of Chicago: mercantile hub, heart of a huge resource empire, center of finance and capital accumulation, and major immigrant receiving area (Issel and Cherney, 1986). Still, the outcome of class struggle in the two cities is different enough to merit a closer look at local circumstances and the course of events as they unfolded. One event, in particular, can help to crystallize the divergent trajectory of the city by the bay.

A victim of the Preparedness Day bombing at Steuart and Market, July 22, 1916.

Photo: Shaping San Francisco

In 1916, San Francisco suffered an incident, known as the Preparedness Day bombing, that was remarkably similar to what transpired in Chicago thirty years earlier: a mobilized working class, a capitalist counter-offensive, anarchist agitators, pitched battles with police, a mystery bomber, falsely accused perpetrators, and a notorious court case that became an international cause célèbre. But workers had greater political power in the city, the legal outcomes were less draconian for the accused, and San Francisco’s working class suffered less of setback – from which it later rebounded more aggressively. As in Chicago after Haymarket, however, San Francisco’s bourgeoisie sought atonement for the sins of class struggle through urban monumentalism, tweaking the city’s landscape – a key point of entry for the urban geographer.

Workingmen’s City

San Francisco was, from the start, a more wide-open place even than frontier Chicago. The Gold Rush of 1848-55 ushered in a kind of republican moment not seen since the days of the American Revolution, at a time when Chicago was already settling into bourgeois order under William Ogden and his ilk. San Francisco politics came under the sway of David Broderick and his Tammany- trained Democrats – the first freely elected Irish government in the world. It took the Vigilantes of 1855 – led by the merchant class – to put down such popular pretensions and the Comstock Silver boom to set off another round of capital accumulation in the 1860s (Senkewicz, 1985).

While the burghers of Gilded Age San Francisco erased much of that legacy to build a proper Victorian city after the Civil War, a newly-mustered working class asserted itself quickly. A branch of Karl Marx’s first international was established under the name of the Workingmen’s Party, which exploded in size and influence after the silver crash of 1875. Soon it was in the hands of a flamboyant Irish orator, Denis Kearney, and pretty much terrorized the city’s bourgeoisie in the late 1870’s. The Workingmen’s Party effectively controlled San Francisco city government from 1878 to 1882, and sent elected representatives to the legislature from around the state. It won the fight to call a second constitutional convention for California, which rewrote the state constitution in 1882 (Ethington, 1994).

The Workingmen’s Party had a radical critique of the railroads, land grabbers, and industrialists, but had its dark side, as well. Kearney’s gang were brutal in their attacks on the Chinese, who made up almost 10% of the city’s population, engaging in racist demagoguery, boycotts of Chinese-made goods, and mob assaults on innocents. Their one great success in the Constitutional Convention was to ban Chinese immigration – which led to a national interdiction in 1882, the first step to the total closure of 1924. Most of their planks against the capitalists were nullified by an alliance of Republicans and Democrats, so on balance the ledger is negative (Saxton, 1971).

The Workingmen’s Party died out after that, and things quieted down with the economic revival of the 1880’s. San Francisco got its own branch of the Knights of Labor in that decade, although they were not as militant as the Knights in the east. Prosperity and exhaustion from the politics of the 1870s meant that things were a good deal calmer than in Chicago during the years of the Haymarket Affair. Nonetheless, class struggle would soon return in spades, as trade union organizing got underway.

Given the attack on the Chinese, one might think that San Francisco was less a city of immigrants than Chicago, or other eastern cities. Yet San Francisco had the highest percentage of foreign born and their children in the 1880s. These were mostly Irish and German, as in Chicago, along with a growing group of Italians and Scandinavians, plus the usual base of English, Scots and Welsh. What is amazing, however, is how rapidly they assimilated into a single white working class, using the Chinese as a foil for their white identity (Issel and Cherny, 1986).

In the early 1890’s, the bourgeoisie organized to quell union uprisings and to bring San Francisco into the post-Victorian era. In the process, they created one of the first employers’ associations in the United States (McWilliams, 1949). With the fall into recession in 1893-96, the bosses were able to seize the initiative and break the first longshoremen’s and sailors’ unions. The capitalists found their political voice in the person James Phelan, son of a 49er turned businessman. Phelan was one of the new generation of college-educated sons of the Gilded Age coming out of the recently-founded University of California at Berkeley and Stanford University (Wollenberg, 1985).

Phelan served three terms as Democratic Mayor, from 1896-1902, and he succeeded in the first order of business for the Progressives, city charter reform. This introduced civil service requirements and streamlined government, and, it was thought, would reduce corruption and working class electoral influence. Phelan then invited Chicago’s Daniel Burnham to come to San Francisco in 1901 prepare a city plan (Kahn, 1979). That came years before the city plan of Chicago, but its baroque vision of radial avenues and classical monuments was never adopted. The main reason it was not put into action was resistance by downtown landowners to changing the street grid and taking some land out of the private market (Brechin, 1999).

Union Labor Power

The failure of Phelan to muster his class behind the plan also had a great deal to do with class struggle in the streets. In 1901, the Teamsters, sailors and dock workers made a crucial tactical alliance, the City Front Federation, that fought with the shippers association to accept union wages. A strike was called in July and lasted until October, including an open gun battle, several worker deaths, and a city on the verge of a General Strike; intervention by the Governor settled the conflict in favor of the workers (Camp, 1947). San Francisco became a Closed Shop city after that, and stayed that way until the First World War. The workers used the county-wide San Francisco (Central) Labor Council and Building Trades Council as instruments for collective action against employers to a degree unparalleled in other US cities, with the surprising effect of welding together the craft-unions of the American Federation of Labor into a united front unheard of before the age of the industrial unions of the 1930s (Kazin, 1987).

Not only did the workers come out of this battle better organized, but they were unified politically against Mayor Phelan, who had openly supported the employers and given them police support. So some of the unions cobbled together the Union Labor Party and managed to throw Phelan out of office, electing Union Labor Party candidate, Eugene Schmitz, in late 1901 (with a good deal of middle class support). In 1905, with official sanction from the two big labor councils, the ULP gained a majority on the Board of Supervisors (San Francisco’s City Council), defeating a Republican-Democratic fusion ticket. Not that this expression of class consciousness and solidarity led to anything terribly radical once the ULP was in office -- this was still America, after all – but it did stop the Progressive movement in its tracks, kept the police on the sidelines, and allowed the unions to solidify their hold on one-third of the city’s labor force. As with so many city machines of the time, however, Abe Ruef, the party’s political boss, and the ULP leaders were playing business for monetary favors and largely neglecting the interests of the class that had put them in office (Bean, 1952).

In the wake of three electoral defeats, Phelan and the city’s Progressives, led by Rudolph Spreckels, would get their revenge, with ‘rid the city of graft’ as their rallying call. They hired the Burns Detective Agency to shadow Ruef. The great earthquake of April 1906 intervened, but by October the Merchants’ Association and leading businessmen called a mass meeting to chase out the ULP. Schmitz and Ruef were soon indicted and convicted in the Graft Trials of 1907, a tremendous show-trial blazoned across the daily papers and interrupted by the attempted assassination of the prosecutor (shades of Dallas 1963, the shooter turned up dead in his cell the next day). In the end, the corruptible Supervisors all got immunity for testifying against Mayor Schmitz and Abe Ruef, the political boss behind the Union Labor Party, who were convicted of bribery (Schmitz’s conviction was overturned on appeal, and only Ruef went to jail)

Nonetheless, San Francisco’s burghers failed to restore bourgeois hegemony, because the Graft Trials revealed the corruption of business as much as the politicians – since the phone companies, water company, trolley companies and land developers were paying Ruef for political services. Of course, none of the businessmen were ever convicted of giving bribes. But the city’s leading lights were badly split, denouncing and turning state’s evidence against one another (Issel, 1989). This is quite at odds with experience in other cities, such as the cohesion of the Commercial Club of Chicago adopting the Burnham plan of 1908 or of the Merchants and Manufacturers’ Association of Los Angeles, which faced down that city’s incipient unions with a united front in the early 1900s.

Despite the graft convictions (which drove Mayor Schmitz from office), the earthquake and fire that destroyed San Francisco ended up helping labor. The whole city’s attention turned to the job of rebuilding and, in rebuilding quickly, business needed workers by the bushel basket. Labor demand was so strong that the unions, especially the Building Trades, were able to lock in high wages and the requirement of a union card to gain employment. Strikes were frequent and the metal workers won the first 8-hour day contract in a U.S. city in 1908. On the other hand, a car-men’s (trolley drivers’) strike against notorious capitalist (and bribe-giver) Patrick Calhoun, owner of the United Railways, failed in the face of a fractured labor movement. The street railway strike of 1907 was a violent affair that saw scores of people killed and hundreds wounded. The business mayor who replaced the disgraced Schmitz sent in the cops on the side of the scabs.

The working class political power that had been shattered by the graft trials had to be rebuilt along with the city. It was, to a large degree. Patrick McCarthy, head of the Building Trades Council, was elected mayor for a term in 1909, rounding out a decade of remarkable labor politics on the Union Labor Party ticket. As one labor historian has said, San Francisco’s labor movement exercised "more power and influence than labor in any other major American metropolitan area" in the first decade of the century – possibly more than any working class in the world at the time (Knight, 1960, p 371).

Civic Improvement

Naturally, the bourgeoisie were quite irritated by this breech of class protocol, and they were not about to relent in securing political power again and in whittling the unions down to size. In the 1910s, the capitalists reorganized with the merger of the Merchants’ Association, Downtown Association and Board of Trade into the Chamber of Commerce. In 1914 a new Merchants’ and Manufacturers’ Association (a name no doubt borrowed from LA’s successful business alliance) was established to confront the unions, but the anticipated offensive against labor was held off until after the forthcoming Panama-Pacific Exposition of 1915. In June 1916, in the midst of a deadly strike on the waterfront, the Chamber of Commerce declared war on the Open Shop and, in a mass meeting of the city's capitalists, created a Law and Order Committee -- echoes of the Vigilantes (Marine 1967).

In the election of 1911, the city burghers recovered the mayor’s office for one of their own, merchant James Rolph, and kept him in office for the next twenty years (including a brief stint as governor of California). ‘Sunny Jim’ Rolph was one those classic characters in American politics, a Bill Clinton or Arnold Schwarzenegger of his age: an Irishman and self-made businessman who could glad-hand everyone, drink like a sailor, and charm working class voters – and who had the good sense to oppose the Open Shop and the Law and Order Committee. The Progressive wing of the Republicans also took power statewide in 1911, behind Hiram Johnson, and instituted a wide-ranging series of reforms, such as the institution of the referendum, initiative and recall, and women’s suffrage. Johnson had, not coincidentally, been a prosecutor in the Graft Trials (Issel, 1989).

The city fathers not only got organized, they decided in 1910 to create a world’s fair to mark the return of San Francisco from the dead, the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915. The great exposition was the kind of temporary monumentalism the modern bourgeoisie love, because after the show is over the false front city of lights could be torn down and converted into a new money- making proposition, the Marina District (Brechin, 1999). That same year they inaugurated a monumental new City Hall, one that rivals any civic building in America, then or since. Modeled on the U.S. Capitol, it manages to be both enormous and elegant, with its symmetric colonnaded exterior, vast dome, and gold-plated cupola. Around a vast, ceremonial plaza in front of City Hall, they placed a Beaux Arts Civic Center, filled out over the next decade with an array of public buildings: city library, state courts, civic auditorium, opera house, and the like (Kahn, 1979).

Although these examples of civic monumentalism are usually interpreted as celebrations of San Francisco’s rebirth and rivalry with upstart cities such as Oakland and Los Angeles, or of the city’s pretensions to imperial power across the Pacific, one cannot forget the bitter taste the class struggles of the 1900s in the mouth of the city burghers. Like Paris in the wake of the 1870 Commune, San Francisco got its own Sacre Coeur, a great white edifice of atonement (Harvey, 2003). Like Chicago in the aftermath of Haymarket, San Francisco erased the memory of working class sins by means of a glorious White City – once in the Panama-Pacific International Exposition and again in the Civic Center.

By 1916, in the run-up to the First World War, there would be more than just a return of bourgeois hegemony. Along with it came the re-ascendance of the right-wing of American politics: blue noses and militarists. One flank of this was the assault on the notorious Barbary Coast, San Francisco’s sin district near the waterfront and Chinatown. San Francisco was by no means unique in this, given the national campaigns for temperance and morality during that decade. Yet San Francisco actually resisted it better than some cities: the Barbary Coast was officially closed in 1917, but the red lights, while dimmed, stayed on until the 1930s and moved to new parts o the city, such as the Tenderloin (Asbury, 1933; Shumsky 1980). And on the religious front, Catholic Archbishops Riordan and Hanna were vocal in support of the dignity of labor throughout the first four decades of the century (Issel and Cherny, 1986).

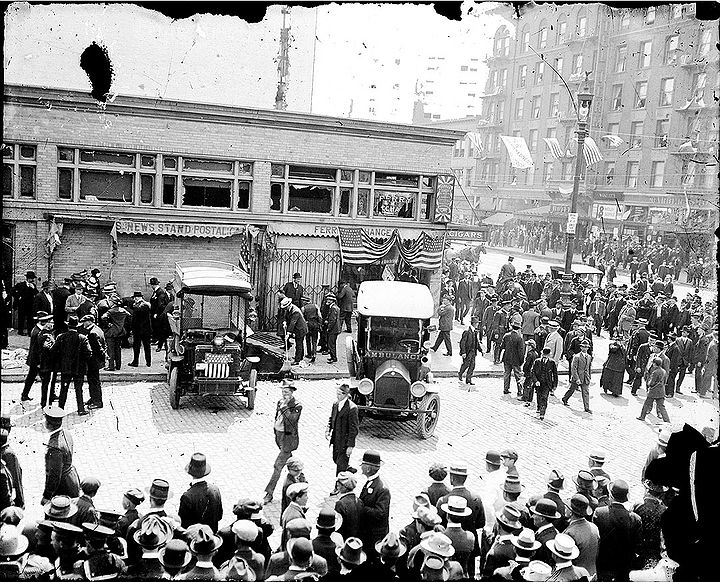

An hour or so after the bloody Preparedness Day bombing, July 22, 1916, at the intersection of Steuart and Market in San Francisco.

Photo: courtesy Emiliano Echeverria collection, with thanks to the Western Neighborhood Project

The militarist wing of the city elite supported a national movement to get the United States into the European war. San Francisco’s weapons-makers, like the Scott Brothers, were enthusiastic about this, as they had been about U.S. conquest of the Philippines in the early 1900s. James Phelan, elected to the United States Senate from California in 1913, became a notorious drum-beater against the Japanese, both at home and across the Pacific (Brechin, 1999). He was San Francisco’s answer to Joseph Chamberlain, with his transit from reforming mayor of Birmingham to Colonial Secretary of Great Britain.

Free Tom Mooney!

This brings us, at last, to San Francisco’s Haymarket Affair. The war- mongers had organized a big parade, as they did elsewhere around the country, for the so-called “Preparedness Day”, July 22nd. They were joined by more than 2,000 organizations and 25,000 marchers. Marching against the drumbeat was a large and vibrant pacifist movement in San Francisco, led by anarchists, syndicalists and trade unionists, part of a national opposition from below and the left – for which many radicals would pay dearly before the decade was over. Coincidentally, the anarchists Emma Goldman, and her lover of the time, Alexander Berkman, were both in the city that year – no doubt making the local capitalists nervous. Berkman was putting out his paper, The Blast!, from San Francisco and had a considerable following on the west coast in that age of peak IWW (Industrial Workers of the World, or Wobblies) activity (Frost, 1968).

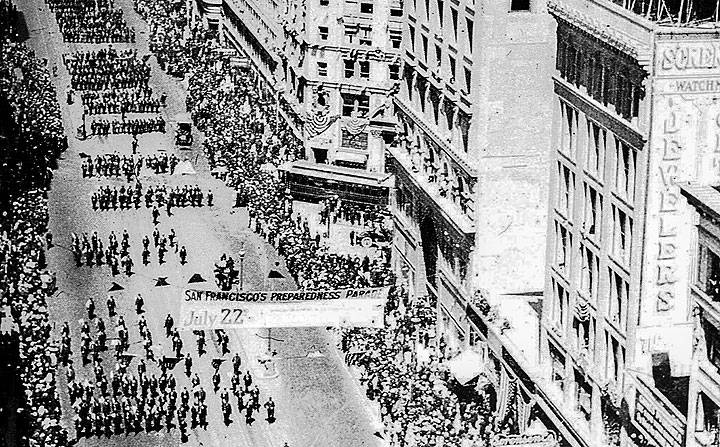

The Preparedness Day parade on July 22, 1916, at apx. Market and 3rd Streets.

Photo: courtesy Tim Drescher

Leading up to Preparedness Day, there were threats of trouble and organizing of counter-demonstrations; the atmosphere was tense. Soon after the march began, a suitcase bomb exploded near the foot of Market Street (across from the Ferry Building), killing ten people and wounding forty. It was a good deal more deadly than the bomb thrown at Haymarket in 1886, though not up to the carnage done on Wall Street by Mario Buda’s wagon-bomb in 1920 (Davis, 2007). San Francisco’s elite were horrified. Without further ado, the police rounded up all the usual suspects, including Goldman and Berkman.

There was little evidence as to who had done the evil deed, and no one ever found out. But, as at Haymarket, there had to be retribution. William Randolph Hearst, himself a San Francisco product, financed the making of one of the earliest propaganda film documentaries in order to fire up public opinion against the wicked anarchists. And, as in Chicago, the D.A. was able to convict on a weak case built around false testimony by police informers (later rescinded) (Gentry, 1967).

Sheriff Tom Finn taking Tom Mooney to San Quentin Prison.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Tom Mooney and Warren Billings, a couple of sometime anarchists, Wobblies, and labor radicals, became San Francisco’s Albert Parsons and Alfred Spies – martyrs to ruling class revanchism. Unlike Chicago, the forces of order were only able to convict two men – far short of the eight Haymarket defendants – and no one was hung. As in Chicago, the left, the unions and their allies organized to defend the accused, who became popular heroes among the local working class and across the country. Goldman and Berkman organized an international defense committee for Mooney and Billings, and protests rolled in from around the world.

Mooney and Billings were, by and large, less impressive characters than Parsons and Spies, and certainly less central to the working class opposition in their city. They were, instead, chiefly street fighters happy for a scrape with the cops. Being often on the front lines of trouble, they were easy targets for the police and prosecutors. One thing we know for sure, however, is that they did not set off the bomb (Frost, 1968). Nonetheless, they were convicted in 1917 on evidence later shown to have been entirely fabricated. So great was the uproar, a commission of inquiry was set up by President Woodrow Wilson and Mooney’s sentence commuted to life imprisonment, like that of Billings, in 1918.

1931 demonstration demanding release of Tom Mooney and Warren Billings.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Therefore, unlike the Haymarket Affair, the Mooney-Billings case did not register as a decisive defeat for the working class. On the contrary, Mooney and Billings became heroes of the left and martyrs to a cause that was far from lost. This was a far cry, as well, from the circumstances in Los Angeles in 1911, when the bombing of the L.A. Times building by the McCarthy brothers led to a disastrous electoral defeat of Job Harriman for mayor and a moral implosion of the Southern California left (Davis, 1990).

Southern Pacific Building, 1918, built over site of Preparedness Day bombing.

Photo: photographer and provenance unknown

Pyrrhic Victory of the Bourgeoisie

In the short run, San Francisco’s burghers appeared to gain the upper hand in their long war with labor and the Left. Nationally, the war-makers would use the Alien and Sedition Act against their opponents, jailing socialist Eugene Debs and Wobbly Bill Haywood and deporting Goldman and Berkman for opposing the war. The Red Scare of 1919 was another hard blow by the forces of repression, with the police break-ins at union, socialist and Wobbly offices across the country and jailing of thousands of activists. AFL unions were busted right and left until almost none remained across the country, and the American Plan and the Open Shop reigned supreme. The doldrums of the Twenties were upon the nation. The only bright spot on the political canvas of the decade was the hasty death of President Warren Harding (every bit as corrupt as the Eugene Schmitz) in 1923—where else, but in San Francisco?

In California, too, the employers’ offensive drove back the unions. The key maritime unions were broken in 1919, followed by the crushing of the IWW organizing effort in San Pedro in 1923. The San Francisco Building Trades Council was still a force to be reckoned with, but its closed shop reign ended in 1921 (Issel, 1989). All was not quiet, however. The Carpenters Union fought a spirited battle against the open shop in 1926, which briefly gained the support of the Board of Supervisors and the Mayor, holding the police at bay; but they, too, went down to defeat.

If the working class of San Francisco was down, it was not out. When the Great Depression and the beginning of the New Deal began to weaken the power of capital, organized labor returned to the city with a vengeance. The longshoremen were again first out of the gate, pushing for higher wages and an end to the ‘shape-up’ system of daily hires. A conference of all West Coast dockers in San Francisco in early 1934 was followed by a break with the company union and then with the leadership of the East Coast-based International Longshoremen’s Union. A strike was called, and tensions ran high. The police killing of two strikers triggered a huge funeral march up Market Street – vastly exceeding the notorious Preparedness Day march in size and enthusiasm – and then to a General Strike of all the city’s unions. The city was shut down for three days (Selvin, 1996).

San Francisco’s General Strike was the first big outbreak of labor militancy across the United States in the 1930s, a decisive decade for the rebuilding of American union power. Furthermore, San Francisco’s labor leadership was far to the left. Two key leaders were Harry Bridges, an Australian, who took charge of the new International Longshoremen and Warehousemen’s Union, and Sam Darcy, the key organizer of the General Strike; both were communists. Darcy was an ex- New Yorker who had been exiled by the national CP as a troublemaker; the hoary Stalinists of New York figured that San Francisco was the next best thing to Siberia. Ironically, New York never had a General Strike in the 1930s (Eliel, 1934).

So San Francisco’s working class came back into its own in the 1930s. The city became, once again, virtually a Closed Shop town. Politically, labor inched back to the table, even though the business class still held the cards. The successor to Sunny Jim Rolph as mayor was Angelo Rossi, who served from 1931 to 1944. Rossi was publicly anti-labor and anti-communist, and called down the police and the National Guard on the strikers in 1934. But even he came up short of opening the port by force or declaring martial law, as the employers wanted, and ultimately he made an accommodation to the reality of labor’s renewed power in the city (Issel, 2000). Finally, the first Democratic Governor to be elected in California in over half a century, Culbert Olson, pardoned Tom Mooney and Warren Billings in 1939. A huge parade in their honor filed up Market Street, as the working class celebrated the return of its martyrs and flexed its collective muscles to show that San Francisco was more than an imperial city of capital. It was their town, too.

Tom Mooney receiving his pardon from Culbert Olson, Jan. 7, 1939.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco, CA

Governor Olson signing papers to release Warren Billings, months after Mooney's pardon, in October 1939.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco, CA

Tom Mooney parades triumphantly up Market Street, after being released from San Quentin Prison, January 1939, after 22 and a half years imprisonment.

Photos: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco, CA

Tom Mooney and crowd on Market Street, January 1939.

Photo: Labor Archives and Research Center, J. Paul Leonard Library, San Francisco State University

Tom Mooney turns onto McAllister from Market during his return parade, January 1939.

Photo: Labor Archives and Research Center, J. Paul Leonard Library, San Francisco State University

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/tom-mooney-returns-1939-llsf-2016-20-mbps-1" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Footage of Tom Mooney on his long-awaited return to San Francisco after 22.5 years in jail for a bombing in 1916 he had nothing to do with. He was pardoned by new governor Culbert Olson and made his way back to SF's Ferry Building where he was greeted by 10,000 people. The city accompanied him on his walk up Market to the Civic Center and this footage was shot near the end of the parade.

Video: from "Lost Landscapes 11, 2016" edited by Rick Prelinger, courtesy Prelinger Archives

Notes

Asbury, Herbert. 1933. The Barbary Coast: An Informal History of The San Francisco Underworld. New York: Alfred Knopf.

Bean, Walton. 1952. Boss Ruef’s San Francisco. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bluestone, Daniel. 1991. Constructing Chicago. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Brechin, Gray. 1999. Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Camp, William. 1947. San Francisco: Port of Gold. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Cronon, William. 1991. Nature's Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. Chicago: WW Norton.

Davis, Mike. 1986. Prisoners of the American Dream. London: Verso.

Davis, Mike. 1990. City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. London: Verso.

Davis, Mike. 2007. Buda’s Wagon: A Brief History of the Car Bomb. London: Verso.

DeLeon, Richard. 1992. Left Coast City: Progressive Politics in San Francisco, 1975-1991. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

Domosh, Mona. 1996. Invented Cities: The Creation of Landscape in Nineteenth-Century New York and Boston. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Eliel, Paul. 1934. The Waterfront and General Strike: San Francisco, 1934. San Francisco: Hooper Printing Company.

Ethington, Philip. 1994. The Public City: The Political Construction of Urban Life in San Francisco, 1850-1900. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Frost, Richard. 1968. The Mooney Case. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Gentry, Curt. 1967. Frame-Up: The Incredible Case Of Tom Mooney And Warren Billings. New York: Norton.

Green, James. 2006. Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, The First Labor Movement, and the Bombing that Divided Gilded Age America. New York: Pantheon.

Groth, Paul. 1994. Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Herod, Andrew. 2001. Labor Geographies: Workers and Landscapes of Capitalism. New York: Guilford Press.

Harvey, David. 1985. The Urbanization of Capital. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Harvey, David. 2003. Paris: The Capital of Modernity. London: Routledge.

Hines, Thomas. 1979. Burnham of Chicago: Architect and Planner. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Issel, William. 1989. “Business power and political culture in San Francisco, 1900-1940.” Journal of Urban History. 16(1): 52-77.

Issel, William and Robert Cherny. 1986. San Francisco, 1865-1932: Politics, Power, and Urban Development. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Issel, William. 2000. “New Deal and wartime origins of San Francisco's postwar political culture.” In, Roger Lotchin (ed.), The Way We Really Were: The Golden State in the Second Great War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 68-92

Kahn, Judd. 1979. Imperial San Francisco: Politics and Planning in an American City, 1897-1906. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Kazin, Michael. 1987. Barons of Labor: The San Francisco Building Trades and Union Power in the Progressive Era. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Knight, Robert. 1960. Industrial Relations in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1900- 1918. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Massey, Doreen. 2005. For Space. London: Sage Publications.

McWilliams, Carey. 1949. California: The Great Exception. New York: AA Wyn.

Miller, Donald. 1996. City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Saxton, Alexander. 1971. The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Shumsky, Neil. 1980. “Vice responds to reform: San Francisco, 1910-1914.” Journal of Urban History. 7: 31-47.

Selvin, David. 1996. A Terrible Anger: The 1934 Waterfront and General Strikes in San Francisco. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Senkewicz, Robert. 1985. Vigilantes in Gold Rush San Francisco. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Soja, Edward. 1989. Post-Modern Geographies. London: Verso.

Stover, John. 1997 (1961). American Railroads. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Walker, Richard. 1998. “An appetite for the city.” In, James Brook, Chris Carlsson and Nancy Peters (eds), Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics and Culture. San Francisco: City Lights Books. pp. 1-20.

Walker, Richard and Daniel Buck. 2007. “The China road: the transition to capitalism in China’s cities.” New Left Review. 46: 1-27.

Waterman, Peter and Jane Wills (eds.). 2001. Space, Place and the New Labour Internationalisms. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Wollenberg, Charles. 1985. Golden Gate Metropolis. Berkeley: Institute of Governmental Studies.