Roots of ''Rolling Stone'' Magazine

Historical Essay

by Jessica Hyman, 2019

| One of the most successful underground publications that resulted from 1960s and 1970s counterculture was Rolling Stone magazine. Founded by Jann Wenner and Ralph J. Gleason in 1967, Rolling Stone quickly gained popularity amongst readers and advertisers. Despite being founded in the counterculture center of the United States, the magazine failed to embrace many of the norms of that community, which is precisely what allowed it to become so successful. Its superficial political coverage, critical music reviews, and experienced writers and editors propelled the magazine to the level of success unknown by other underground publications. |

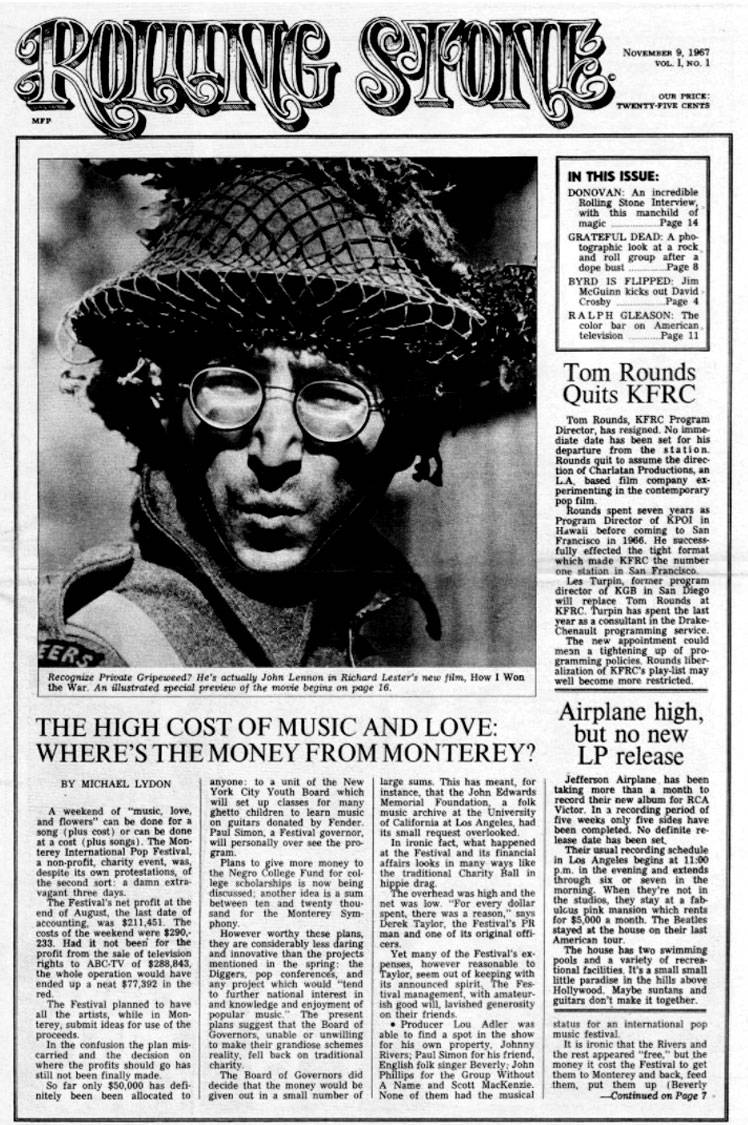

Cover of the first print of Rolling Stone magazine (1967)

In November of 1967, from a small print shop in the Haight-Ashbury, Jann Wenner, a twenty-one year old English-major Berkeley drop out, and Ralph J. Gleason, a jazz critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, ran the first prints of their magazine titled Rolling Stone. Both determined writers and fans of rock and roll, Wenner and Gleason used their combined experience to create a publication that documented and later influenced the music industry. The success of the magazine was rooted in Wenner’s experience as an editor, as well as the rise of counterculture in San Francisco.

Rolling Stone was inspired by the surge in underground writing and print in San Francisco during the 1960s and 1970s. Wenner experienced this throughout his time spent as an editor for a branch of the popular, San Francisco-based, muckraking magazine Ramparts. (1) As a political publication, Ramparts was known for its criticisms and attacks of national policies and figures, which caused advertisers to be wary of sponsorship due to the risk of negative association. (2) This meant that its predominant source of revenue was from subscribers rather than advertisers. Gleason also served as an editor for Ramparts, although he wrote for the main publication rather than Sunday Ramparts like Wenner. Both men spent much of their time at the magazine attempting to emphasize the importance of rock and roll, only to be contested by editor Warren Hinckle. Hinckle’s dismissive attitude towards the genre eventually caused Gleason to leave Ramparts in early 1967. Wenner, however, stayed with the publication until it folded in early May of the same year because his position gave him access to various musical artists. (3) That summer, the Summer of Love in San Francisco, served as a catalyst for the start of Rolling Stone. With both Gleason and Wenner out of a job at the end of summer, the two began gathering funds to start a publication that would give a serious voice to musicians and document the culture surrounding rock and roll.

Wenner’s time at Ramparts critically influenced the direction that he chose for his own magazine. With $7500 to the magazine’s name, Rolling Stone did not have the financial capacity to rely solely on readership like Ramparts. (4) As a result, Wenner encouraged and directed his writing staff to stay clear of radical political topics and statements in order to bring in advertisers and, as a result, money. (5) The first few prints of Rolling Stone featured articles that covered political topics like “Joanie Goes to Jail Again,” which promoted anti-war sentiments, and a pro-marijuana cover story regarding the arrest of several members of San Francisco band, The Grateful Dead. (6) While these articles gave the illusion of being political, they did not truly critique the political system or give readers impetus or resources to change or act. Instead, they simply reported. By repeating back to the public the same countercultural sentiments that were popular amongst San Franciscan youth, Wenner was able to create an easily digestible publication that was both entertaining and commercial.

The superficial political coverage made the magazine popular and allowed it to root itself in San Francisco counterculture without taking on the dangers of being a countercultural magazine. Its music reviews made it popular among San Franciscans because of its coverage of local bands like The Grateful Dead, Jefferson’s Airplane, Country Joe and the Fish, and many more. The magazine provided just enough coverage of life in San Francisco to make it appear that it was local. But, from the beginning, Wenner had described wanting the magazine to be larger than just San Francisco. (7) As a result, Rolling Stone was never really meant to be a part of the city, but Wenner used its people and its culture as a starting point.

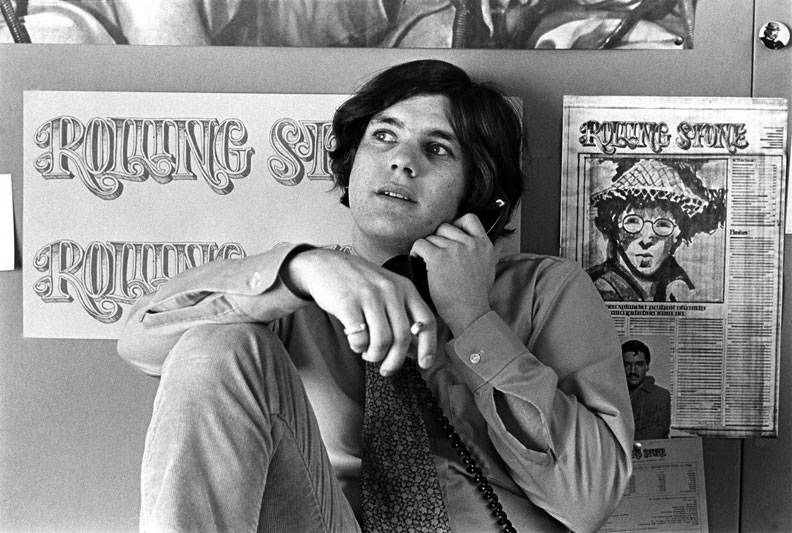

Jann Wenner with the cover concept for the first print of Rolling Stone (1967).

Photo: Andy Greene

This sentiment is seen in the evolution of advertisements in the magazine. In the beginning, its ads centered around local shows, shops, and businesses. But as the magazine grew, its ads began to shift towards large record companies like ABC and other corporations. (8) These initial supporters gave the magazine enough funding to run the first few issues. They, however, were eventually outpriced by larger corporations hoping to find space in the magazine. (9) With increased interest, the length of the magazine increased from around thirty pages to upwards of seventy pages by the mid-seventies. Within these pages, more space per page was dedicated to ads and, because of the increase in length, more companies were able to buy full pages to promote their products or services. (10) Initially, a majority of pages were dedicated purely to content. The prints towards the end of the decade hardly had any spreads without at least one ad. Rolling Stone was well on its way to total commercialization.

This departure from its initial advertising strategy signified a shift away from the aspects of the magazine that first drove its popularity. In the beginning, the publication’s success can be documented through its “Correspondences” section, which contained reviews, critiques, and responses sent in by readers. Out of state readers wrote in to praise or vehemently disagree with the articles written. (11) These readers appeared to look to Rolling Stone and other underground publications in the Bay Area for musical guidance. Locals, on the other hand, explained specifically that it was Rolling Stone’s minimal ads, carefully thought out critiques, and clear standards of writing, that made it preferable to other publications at the time like The Beat. (12) They read the magazine for coverage of hometown bands and to get updates on the local scene. Historians and journalists like Robert Draper, author of Rolling Stone Magazine: The Uncensored History, agree that the support of the local community was vital in the early success of the magazine and that the music focus and attention to detail took away some of the grit that made other publications controversial, but allowed it to thrive when much of the era’s musical journalism was dedicated to short, superficial pieces. (13) However, as the magazine grew, it lost much of the local charm that made it popular from the start.

As a result, in 1977, Rolling Stone moved to New York, which symbolized the publication’s final departure from its origins. This decision came two years after the death of Gleason, who had used his column called “Perspectives” to provide insight into the San Francisco’s problems and provide criticisms and reviews of city life. His role at the magazine centered around keeping the magazine rooted in San Francisco and lending his expertise and name, which was a significant part of initially drawing in investors. (14) In the two years between his death and the magazine’s move, Wenner worked to nationalize the magazine by decreasing the number of articles that covered local topics like the Haight Ashbury free clinics and incorporating bands that were making waves in rock and roll culture, but were not started in San Francisco. (15) It left the city without really leaving a mark other than its name; having used the culture from which it was born for profit, Wenner achieved his goal of making a magazine as large as his ambition.

Notes

1. Draper, Robert. Rolling Stone Magazine: the Uncensored History. Doubleday, 1990, p 50.

2. Ibid., 51.

3. Ibid.

4. Greene, Andy. “Rolling Stone at 50: Making the First Issue.” Rolling Stone Magazine, 25 June 2018.

5. Richardson, Peter. “The Magazine That Inspired Rolling Stone.” The Conversation, 16 May 2019.

6. Wenner, Jann, and Ralph J Gleason. “Rolling Stone Magazine.” Rolling Stone Magazine, Nov. 1968, 8-16.

7. Nocera, Joseph. “Rolling Stone Magazine: The Uncensored History.” EW.com, Entertainment Magazine, 8 June 1990.

8. Wenner, Jan. 1970 – May 1975.

9. Nocera, “Rollnig Stone Magazine”.

10. Wenner, Jan. 1970 – May 1975.

11. Wenner, Nov. 1967 – May 1977.

12. Wenner, Jann, editor. “‘Correspondences.’” Rolling Stone Magazine, 24 Feb. 1968, p. 2.

13. Rolling Stone. “'Rolling Stone: Stories From the Edge': 10 Things We Learned.” Rolling Stone, 25 June 2018.

14. Draper, Rolling Stone Magazine, p.75.

15. Wenner, Jan. 1970 – May 1975.