Pacific Renaissance Plaza Anti-Eviction Coalition

Historical Essay

by Karen Rodriguez-Ponciano, 2015

Pacific Renaissance Plaza in Oakland between Franklin and Webster

Photo: Karen Rodriguez-Ponciano

| In April 2003, residents of 50 units of affordable housing received eviction notices in Oakland’s Chinatown Pacific Renaissance Plaza, a product of urban redevelopment spanning two decades. These residents came together with community activists to fight the evictions, to allow residents to remain in their units, and to preserve the community's right to affordable housing. This became a five-year battle, and in 2015, construction of 50 replacement affordable housing units—a stipulation won in the struggle—have still not been built. |

The Origins of Pacific Renaissance Plaza

Located in the heart of Oakland’s Chinatown, between Franklin and Webster, is the Pacific Renaissance Plaza, a mixed-use complex that consists of residential, commercial and civic spaces. Comprising 90,000 square feet, the multi-tenant commercial plaza includes 68 commercial condominium units, a Bank of America branch, the Alta Bates Summit Medical Center, an HSBC bank branch, the Oakland Asian Cultural Center, and the Asian branch of the Oakland Public Library.(1)

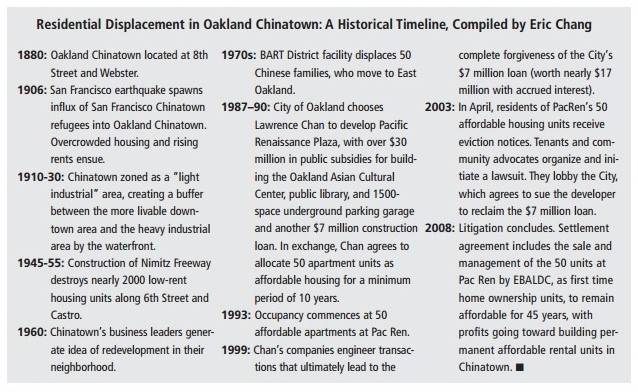

The history of the Plaza goes back to the 1960s, when BART system construction transformed Oakland and Chinatown razing thousands of units of affordable Chinatown housing(2) and displacing small businesses. The business sector of Chinatown wanted the space to be used for commercial purposes, others wanted nonprofits and affordable housing to be part of the mix. Business leaders raised tens of thousands of dollars to fund a study in order to convince the city to allow foreign developers to invest their money. Many saw investment in the neighborhood as a way to revitalize the community. The city government agreed, and declared Chinatown a redevelopment zone.(3)

For the following two decades, the Chinatown neighborhood actively sought to stay involved in the planning process. A Project Area Committee formed, and residents joined to make their voices heard.(4) Living in the era of the Black Panthers and the International Hotel housing struggle, Oakland Chinatown community activists fought for community benefits in the plan.(5) One pressing priority was to replace the housing that had been lost to previous redevelopment projects. Some of these constituents didn’t share the business owners’ vision for how redevelopment should proceed. The discussion and debate continued through the ‘70s and ‘80s. Ultimately, the different factions were able to resolve their differences and come up with a plan for a center that contained both businesses and cultural organizations.(6)

Agreements for the development were signed in 1987 and 1990. The City chose developer Lawrence Chan for the project. Chan was “a multi-millionaire giant” who owned the Oakland Marriott Hotel and the Oakland Courtyard by Marriott Hotel and ran the Oakland Convention Center. He also owned the Parc 55 hotel in San Francisco, the Park Lane Hotel in Hong Kong, and many other properties worldwide. His family’s companies owned properties in Hong Kong and other parts of Asia, Europe and North America.(7) City staffers preferred Chan over the other developers because they believed he had the stronger finances to guarantee the project’s completion.

Under the final Pacific Renaissance development agreement, the City loaned Chan $7 million to assist with construction in addition to over $30 million in public subsidies for building the Oakland Asian Cultural Center, a public library, and a 1500-space underground parking garage.(8) The city redevelopment agency aggregated the land on which the Renaissance Plaza now stands and sold it to Chan with the understanding that when the project made money the city would get a share of the profit as part of the return. The city of Oakland also allowed Chan and his company to pay $8 million less than value of the land that the development was built on. In exchange, Chan was to build fifty affordable housing units, and the units would be renegotiated at the end of 10 years. Although the developer originally promised to build the various elements at no cost to the City when he was seeking development rights, the city of Oakland ended up investing an additional $10 million into building the garage, the library and the cultural center.

Chinatown’s Pacific Renaissance Plaza finally opened in 1993.(9) It was considered a real victory for Chinatown. It signaled change from a Chinese-centric neighborhood to a multicultural and pan-Asian identity. Hundreds applied for the units. Getting in was like hitting the jackpot, allowing low-income families to have a place in what was considered “a five star hotel.”(10) Applicants were screened for eligibility based on income to live in its mostly one- and two-bedroom units.

The affordability expiration date and the conflict

Fast-forwarding 10 years, in April 2003 over 40 tenants of the Pacific Renaissance Plaza —mostly elderly and low-income folks—received eviction notices. The owner claimed that he was no longer required to maintain their units as "affordable housing," and thus he was going to sell the units as market-rate condominiums.(11)

The evictions stunned the mostly elderly Chinese residents. They said no one had told them that the units would cease to be affordable. One of the tenants was 87-year-old Yen Hom. Her son, Art Hom, remembers how she got the news. “She got this notice in the mail that asked her to come up with $300,000 to buy the apartment or move,” recalls Hom. At first, Yen Hom couldn’t even understand the letter, which was written in English. Her son had to read it for her. “My mother felt hopeless and helpless and we all felt pretty vulnerable,” he remembers. “At that time we were thinking we had no choices.”(12)

The residents did not know about the 10-year expiration date for the affordable housing units, but the Oakland city did. According to Adam Gold of Causa Justa/Just Cause Oakland, one of the community groups that joined in to support the tenants, the developer sent a letter to city officials alerting them that the 10 year agreement was about to expire.(13) A provision in the agreement established in the ‘90s gave the city an option of buying it. Chan priced each unit at $450,000. A separate city calculation priced the units at $350,000. After several months, Robert Bobb, the city manager, wrote back saying the city was aware of the situation but had no money to buy back the apartments and that Chan should go ahead and sell the property.(14)

Some tenants reached out and contacted some of the local organizations that could potentially help them. East Bay Community Law Center’s (EBCLC) Margaretta Lin said “first

they contacted the Tenant Union, the Tenant Union contacted Causa Justa/Just Cause Oakland, then Causa Justa/Just Cause Oakland contacted the EBCLC and so forth.” Yen Hom decided to fight her eviction. Her son says she was empowered by the battle. “My mother seemed to have found her voice and was able to say, ‘What’s the next step? Let the Sheriffs come. If they come, well, let them drag me out.’” However, Art also mentions that it was difficult to reach out to the other tenants and convince them to also fight their evictions. Most of them were scared and decided it would be easier for them to leave than to stay. Chang said even most lawyers turned him away at first.(15) Francis Chang’s parents also stood up against the eviction, joining with Art in a lawsuit against Chan in the fight for their parents’ homes.(16)

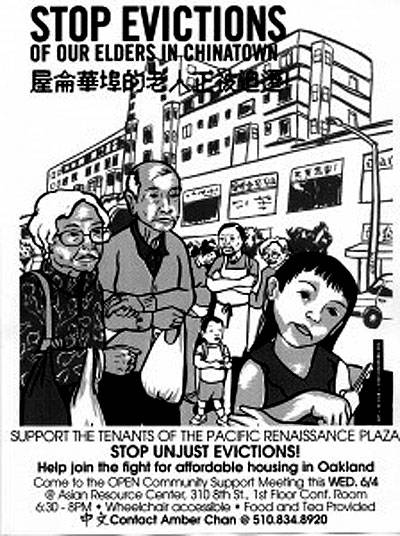

The Stop Chinatown Evictions Coalition

The Stop Chinatown Evictions Coalition (SCEC) formed quickly. Community members and members of different social justice organizations, Chinese community groups, and housing activists decided to join together with the residents in the Pacific Renaissance Campaign to demand that the tenants be allowed to stay and that the units be preserved as permanently affordable housing. Along with Causa Justa/Just Cause Oakland and the EBCLC, coalition members from prominent organizations included Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN), the Chin Jurn Wor Ping Evictions Committee (CJWP), United Seniors of Oakland and Alameda County, Oakland Tenants Union, and Alan Yee of Siegel & Yee.

The attempted evictions in the Pacific Renaissance Plaza took place in a climate of increased social justice activism in the Bay Area, particularly activism involving environmental justice and youth organizing, and at a time of increasingly difficult economic, political, and social conditions for working class, poor, and immigrant families.(17) The Coalition built upon networks formed among organizations and individuals during previous work on housing issues in Oakland and anti-war mobilizations.

The coalition members knew that the opportunity to live at Pacific Renaissance meant more than just affordable housing, it meant also access to doctors and other service providers speaking their languages, proximity to friends and family, and accessibility to community churches, temples, and schools.(18) Many tenants in the affordable units were elderly and disabled; a few were young couples with children. Most were new immigrants and non-English speakers of Mandarin, Cantonese, and Vietnamese. The Pacific Renaissance Plaza was a significant aspect of the lives of many, and the coalition was willing to fight for it.

The initial goals of the SCEC’s campaign were to stop the evictions, to secure the right to stay for the few families who had not moved out after the eviction notice, and work for the right of return for those who had. The first phase of the campaign against the evictions revolved around a highly active and publicly visible effort, and lasted for six months until September 2003. Community members asked people in Chinatown to sign petitions to the government to stop the eviction and held community meetings with local government representatives in the effort to hold the developer and the city of Oakland accountable for the situation that the tenants were facing. The activists were able to join forces with City Council members and other politicians to demand officials to stop the evictions and launch an investigation into Chan's business dealings, including the $7-million city loan Chan had not paid back and which had been forgiven. The plaza had been built with public money, so advocates argued that the developer had an obligation to the community.

The psychological and emotional toll on those faced with eviction is severe, and for seniors, this may even result in serious health complications.(19) Thus, seniors rights organizations advocate strongly for the right of elders to age in place. Over the course of the lawsuit, some elderly tenants fell ill immediately and died in the first few months. Other tenants’ health deteriorated rapidly. Several were forced to enter nursing homes. One tenant’s diabetes became severe; he lost his eyesight and use of his legs.

Community groups then turned up the heat on Chan. Weekend protests were planned with targets including Chan’s residences in downtown San Francisco and Hillsborough. In an interview response, the 48-year-old developer said he had done nothing wrong. "The activists are using these elderly residents to put forth their agenda," he said. "They are blowing this out of proportion." He claimed that the 10-year agreement had been included in the lease that all the residents signed before moving into the units and that he had acted according to the agreements established with the city. However, one of the attorneys who was involved with the case, mentioned that for many cases, the lease did not provide appropriate translation for the tenants and did not provide clear, appropriate information according to the needs of the tenants who were not proficient in English.(20) In response to the accusations, Chan responded: “My business arrangement is with the city and I have not heard from the city that we have done anything wrong."(21)

A closer look into the campaign

As in the fight for the International Hotel in San Francisco decades earlier, an increasingly diverse and intergenerational group of protesters took up the cause. Art said his mother was celebrated as a hero. “Now, this is quite unusual for an 87-year-old woman who all her life has pretty much not had any political power at all,” he pointed out. Many tenants who were elderly actively participated in the campaign. Despite congestive heart failure (she uses, at times, a cane, a walker or a wheelchair), Art’s mother had been the centerpiece of rallies, addressing the crowd in Cantonese through a bullhorn, holding a sign in English and in her native language, “We Will Not Be Moved.” Art remembers bringing his mother to one of many hearings at City Hall. “I’m just wheeling my mom up in a wheelchair, and we see people surrounding her as we enter the meeting hall, holding signs, doing street theater, painting renditions of my mom’s life experience in a mural,” he says. At that moment, he says he felt they “had a sense of community and sense of belonging, feeling heard, validated, understood.”(22)

Francis Chang actively participated in the campaign because his father was 93 years old and his mother, who was 80 years, was on dialysis and could not go. When reflecting about the coalition and APEN’s contribution, Francis Chang said that “It was a long, hard campaign going; we had difficult time inside and outside of the court. We faced challenges from the owner; many tenants passed away during the long campaign including my mom. We had no funds to sustain this campaign, but APEN was there to help. They provided space for us to meet every week. They appealed to [their] member[s] in a call for support from local residents and planned out strategy with Bay Area media for public support. If I am not mistaken, APEN’s hand was already full with other ongoing projects when eviction case happened. But [they] still took us on with full support.”(23)

In one reflective paper, members of CWJP wrote about their difficulties: “We struggled to talk to the tenants in our broken Chinese. They began to finally open up after six months of community meetings. Through gatherings, they began to allow themselves to feel angry, and this united them in a collective struggle.” However, together with the tenants, the activists re-envisioned the meaning of community, and offered “staying in place” as an act of defiance to centuries of forced movement. “What was won was a little piece of something we might call resistance to the seductions of global capitalism,” writes CWJP, “imagining alternatives that reflect our communities’ strongest self-image, honoring past struggles, and creating a future where human rights, justice, and dignity are valued and honored.”(24)

The coalition was full of vitality and diversity. Youth and arts organizations were included. Researchers, artists, and organizers were members. The campaign encouraged each member to help out in the ways that they felt most strongly about. Multilingual and cultural abilities allowed some of to act as interpreters between the lawyers and the tenants while other skills, interests, and networks allowed other members to play roles of liaisons with other affordable housing advocates, writers and designers of press releases and pamphlets, and community outreach conductors to students and religious groups.(25)

In addition to the activist perspective on political education and movement, the Pacific Renaissance tenants brought a strong cultural component to the campaign. In “From Moving feels like Home”to “We will not be moved!,” Diana Pei Wu, a member of CJWP provides an analysis of the dynamics and lessons of this campaign: “While professional activists and

advocates focused on the legal aspects of the campaign, youth and young adult activists also felt that cultural work was an important aspect of mobilization. These young people added to the campaign’s cultural productions that emphasized healing collective injuries and celebrating community and identity in order to motivate collective action.” CJWP members wrote and performed street theater and poetry, painted tenants’ stories and Chinatown’s struggles on canvas and glass, created a video-poem that was widely shown, and provided documentation of years of action through photographs, audio recordings, and writing.

The Legal Battle

At first, the City of Oakland backed developer Lawrence Chan. They said that it was unfortunate that the tenants would be displaced, but there was nothing the city could do as Chan and his companies had lived up to all their commitments under the development agreements. Roy Schweyer, director of Oakland's Housing and Community Development office, agreed with Chan's version of events. "As part of the loan agreement, we were required to buy the project or forgive the loan," he said. "When we could not afford to purchase the units, the loan was considered repaid."(26)

Lawyers for the tenants in the community groups looked at wrongdoing by both the developer and the city. Margaretta Lin, one of the main attorneys involved with the case, mentioned that the legal team made an exhaustive research on the matter in order to make a strong case against Chan. They “reviewed the lease, papers and all the documents that we had,” said Lin.(27) After the legal team reviewed the agreements and the facts, the tenant advocates discovered that the tenants had been overcharged $2 million on their rents and that the city had been tricked into forgiving a total of $16 million in debt.

Activists and tenant advocates presented reports to the City Council detailing Chan's broken agreement with the city and the residents. They threatened to sue both Chan and the city if the council did not announce its intention to halt the evictions and develop a plan to recoup the money. In an interview, Vivian Chang, an organizer for APEN, said that they were looking to hold the city accountable and not just the developer. "There are lessons here for other cities," said Chang, "Officials have a responsibility to assure adequate affordable housing and they should be held accountable to monitor any agreements they make with developers like Chan."(28)

Loss of momentum and moving slowly towards the goal

The second phase of the campaign, which began in at the end of 2003, was characterized by a lack of clarity within the coalition about strategy. Wu describes a “lack of trust and understanding among coalition members and organizations, and the slowness of the legal process combined to produce a situation in which the coalition lost the capacity to continue the highly public nature of the campaign.” Some organizations had left the coalition and those who remained were divided amongst the possible routes to continue with the campaign. CJWP argued that pursuing one lawsuit against the city was not going to be sufficient to maintain the momentum of the community campaign.

The coalition even disagreed on the framework of the campaign. The early decision to frame the issue as one of seniors’ rights and low-income affordable housing in Chinatown had been sufficient to “mobilize the Bay Area-wide Asian-American community and several prominent Oakland organizations and to convince these organizations to apply political pressure to Oakland City Council members and the developer by participating in several highly visible public rallies.” However, some involved expressed that this framework was “problematic” and suggested to move away from the portrayal of the tenants as “powerless” and “victims” than as “survivors and actors in their own lives”.(29)

Coalition members continued to support the family members of the elderly tenants who emerged as leaders from the campaign, and they continued to support the legal cases by planning occasional public events. However, the momentum of the campaign had slowed. Art describes what followed was a “stalemate [that] continued for a long while.”(30) Not without conflict, the coalition decided to focus most its efforts in following the legal path to obtain its goals. Coalition members still hoped to preserve affordable housing units in Oakland Chinatown, but some members wondered whether they should continue fighting specifically for the units at Pacific Renaissance Plaza.

The City of Oakland joins the fight

In December 2004, the City of Oakland, in part due to community pressure and negative publicity, finally agreed to sue the developer for “transactions and false statements that duped the City into forgiving the $7 million loan and any interest in the property.” Now joined by the city, tenants and community representatives asked to let the remaining tenants stay in the Pacific Renaissance until the end of their lives. They also demanded that the tenants be paid back for the overcharged rent, that Pacific Renaissance units be sold to medium income buyers at below market rate, and that the buyers sell in the future at below market prices.(31)

After nearly five years of legal and political maneuvers, seeing that he could lose the lawsuit, Chan and his attorneys agreed to a settlement. In the final settlement, the affordable housing units at Pacific Renaissance Plaza were sold to a local non-profit housing developer, the East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation (EBALDC) at a set price. The settlement stated that, “The 50 existing units will be sold as affordable moderate-income condos, with a lifetime lease for the one remaining tenant.” These sales, after paying off the purchase loan and the city's legal bills, would raise enough money to develop approximately the same number of permanently affordable rental units nearby in Chinatown.(32) It also established that EBALDC would sell the units at an affordable market price to homeowners. The city approved the settlement in September 2007. The sale to the non-profit housing developer closed at the end of 2007.

The unexpected and perseverance

EBALDC is a nonprofit community development organization that “builds healthy, vibrant and safe neighborhoods in Oakland and the greater East Bay”.(33) From the beginning, EBALDC provided support as a non-profit developer and housing expert to the coalition members. EBALDC’s Ener Chiu, who was involved in the campaign, mentioned that “EBALDC started getting involved with the coalition because [we] build affordable housing, and people from the city started asking assistance for the coalition group–help with legal documents and affordable housing information. The coalition had developed a relationship with EBALDC and trusted the non-profit to take on the task to build affordable housing units.”

Chiu explains how things did not go according to plan, “We estimated that the buy price for Larry Chan was $4 million and that the city fees were also $4 million, and we projected that we were going to be able to sell the units for $11-12 million. This left us around $2-3 million after all the expenses for the development of a new project.” However, what ended up happening is that when EBALDC closed the transaction in 2007, before having the opportunity to start selling the units, the market collapsed. Condos in the market would sell for only 50% of their value. “We were left holding these units, but we could no longer sell them at the prices that we needed to pay the bank loan, the city, and [build] the affordable housing.”(34)

The project stayed on hold until recently. In 2015, Chiu shares that, “We are just coming back to the point where we are being able to sell the units again.” Now condos downtown are in demand again at higher prices since Oakland is part of the Silicon Valley peripheral market. On May 11, 2015 EBALDC had sold 34 units and by the end of the month they were expecting to have sold 37. Chiu continues, “The project has been surviving because as an organization we were able to absorb the costs.”(35)

On May 12, 2015, EBALDC celebrated the end of a chapter and the beginning of a new one. In the event called “The 11th and Jackson Groundbreaking,” EBALDC announced the construction of a new family affordable housing building. Chiu shared, “We finally have a piece of land to build affordable housing. We are meeting our promise to the city and the coalition to build new, affordable housing in Chinatown – which is really desperately needed right now.”(36)

Notes

1. LOH Realty and Investments, “The Project.” Pacific Renaissance Plaza (Accessed May 1, 2015)

2. Eric Chang. “The Fight for Pacific Renaissance Plaza: An (Un-Politicized) Overview Part I.” CJWP Historical Documentation Project (Accessed April 23, 2015)

3. Audrey Dilling. “Envisioning a revitalized Chinatown in 1960′s Oakland”, June 16th 2010,

[http://blog.sfgate.com/kalw/2010/06/16/envisioning-a-revitalized-chinatown-in-1960s-

oakland/ KALW]. (Accessed April 23, 2015)

4. Ibid.

5. Chin Jurn Wor Ping. "The Right to Affordable Housing Organizing and Winning in Oakland Chinatown." [<http://reimaginerpe.org/files/CJWP.Rights.16-1-17A.pdf Race, Poverty and the Environment: A Journal for Social and Environmental Justice] 16.1 (Spring 2009): 1-6. Urban Habitat. Urban Habitat, 2009. Web. April 8, 2015. (Accessed March 20, 2015)

6. Dilling, KALW.

7. Alex Cuff “Lawrence Chan Endorses Displacement and Homelessness.” Poor Magazine:Prensa pobre. (Accessed April 10, 2015)

8. Michael Rawson, Director of The Public Interest Law project and legal advisor in the campaign. Interview by author, April 17, 2015.

9. Ibid.

10. Chang, CJWP Historical Documentation Project.

11. Chen, Adelaide. "Oakland Tenants Win Settlement." Asian Week: The Voice of Asian America. N.p., September 28, 2007. Web. April 7, 2015.

12. Sage, Melody. "A Mother Finds Her Voice in a Fight to save Her Home." KALW, February 22, 2012. Web. April 9, 2015.

13. Adam Gold, from Causa Justa/Just Cause, member of the coalition. Interview by author, April 1, 2015.

14. Chang. CJWP Historical Documentation Project.

15. Margaretta Lin, EBCLC attorney, legal advisor of the coalition. Interview by

author April 14, 2015.

16. Sage, KALW.

17. Wu, Diana Pei. From "Moving Feels Like Home" to "We Will Not Be Moved!"Diss. Comp.

Institute for the Study of Social Change. UC, Berkeley, Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management, 2006. Berkeley: ISSC Fellows Working Papers: ISSC

WORKING PAPER SERIES, 2006. From "Moving Feels Like Home” To “We Will Not Be Moved!”: Immigrant Communities Facing Evictions and the Role of Young People’s Organizing, Oakland Chinatown, CA, 2003-2005. [http://www.academia.edu/395109/From_Moving_Feels_Like_Home_to_We_Will_Not_Be_Mov

ed_ Academia], March 28, 2006. Web. April 7, 2015.

18. Rayburn, Kelly. "Deal Is Reached in Chinatown Eviction Lawsuit." Inside Bay Area. N.p., September 20, 2007. Web. April 9, 2015.

19. Sage, KALW.

20. Rawson. Interview by author, April 17, 2015.

21. Chang. CJWP Historical Documentation Project (Accessed April 23, 2015).

22. Sage, KALW, February 22, 2012. Web. April 9, 2015.

23. Chang, Francis. "Asian Pacific Environmental Network." Asian Pacific Environmental Network. N.p., 6 May 2013. Web.(Accessed 10 Apr. 2015)

24. Wu, [http://www.academia.edu/395109/From_Moving_Feels_Like_Home_to_We_Will_Not_Be_Mov

ed_ Academia].

25. Ibid.

26. Chang. CJWP Historical Documentation Project (Accessed April 23, 2015).

27. Lin, Interview by author April 14, 2015.

28. Chen, Asian Week: The Voice of Asian America.

29. Wu, [http://www.academia.edu/395109/From_Moving_Feels_Like_Home_to_We_Will_Not_Be_Mov

ed_ Academia], March 28, 2006. Web. April 7, 2015.

30. Art Hom. Interview by author April 17, 2015.

31. Wu, [http://www.academia.edu/395109/From_Moving_Feels_Like_Home_to_We_Will_Not_Be_Mov

ed_ Academia].

32. Ener Chiu from EBALDC. Interview by author May 11, 2015.

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid.

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid.