Once More Unto the Bridge, Dear Friend

"I was there..."

- "Foundsf.org is republishing a series of "Tales of Toil" that appeared in Processed World magazine between 1981 and 2004. As first-hand accounts of what it was like working at various jobs during those years, these accounts provide a unique view into an aspect of labor history rarely archived, or shared.

by Primitivo Morales

—from Processed World #13, published in Winter 1985.

Between Oakland and San Francisco there stretches an 8-mile-long ribbon of steel and concrete called the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, or the "Bay Bridge." It has two decks—one East and one West, each of them with five lanes. It is well lit, has emergency phones, railings, etc. It is my nemesis. This is the tale of a courier, or officially an "Outside Document Handling Clerk." I'm not sure what the 'outside' refers to. I drove a Chevy van across the Bridge five times a day, rain or shine. Monday, Wednesday and Friday I started at 10:00 AM, the other two days at noon. With luck I could be punching out by 9:00 PM. I was salaried (about $750 take-home), no overtime, little insurance (workman's comp), no union, no "ins" with the cops, no advancement.

The route was: Downtown SF, Port of Oakland, Hunter's Point SF, downtown SF, downtown Oakland, downtown SF, downtown Oakland, Port of Oakland, downtown SF, downtown Oakland, Port of Oakland, Downtown Oakland, South San Francisco, downtown SF, SFO (airport), Burlingame, San Leandro, downtown Oakland, downtown SF, clock out.

I worked for a company which had contracts with shipping companies and various freight brokers to move documents around. About half of my fellow serfs were bike messengers and the rest were drivers. There were two bosses—"Glenn Hires, Harry Fires." We worked out of a basement in a brick building in the landfill area of SF's financial district. We had a set daily route; I was responsible for moving the paper of one of the largest west coast shipping lines—American President Lines. They had a contract with my boss to avoid paying in-house (union) workers. More than half of my day was spent going between the company's main offices; the port facilities, the freight cashier in SF, the warehouse, and the Hunter's Point Shipyard where they were having some of the rustbuckets refurbished (said one worker "You couldn't pay me to go out of the Bay on one of those"). At night I made a run to South San Francisco to Federal Express, and later in the night to the airport and south to Burlingame to a huge liquor warehouse and some freight types, then across the bay to the Monkey Wards warehouse, and then back to the APL stuff.

I liked: the bay and the chance to meet lots of people: clerks, teamsters, longshoremen, other drivers, airport workers, shipyard workers, secretaries, and even bosses. I also liked not having a supervisor looming over my shoulder at unannounced intervals. The weather was lovely, as were the lights of the city. I liked being able to smoke a joint and listen to the radio (I once heard an AM radio station play John Coltrane while the sun was out!). I liked the challenge. I didn't like: cabbies, cops, shitty drivers (lots of all of these), rain, the Bridge, Friday traffic, unreal demands on time, bitchy secretaries and truculent assholes.

It was an odd job; mostly boring—driving or waiting around for some clown. Sometimes I was frustrated; waiting for the one elevator that goes to the underworld—those basements and loading docks that most people never see, or waiting for the traffic to sort itself out. Some of it was aggravating—jerks that play games to get themselves a whole 10 feet farther ahead (look, I move stuff that has deadlines like planes departing and I don't do this shit—what's so important?). At times it was funny, like the three times I saw people run into police cars. Occasionally there were moments of sheer terror—pedestrians that appeared out of nowhere, being rear-ended on the bridge, that sort of thing.

Everybody can have a bad day, but for those of us who get to romp on the highways and byways of the U.S. a bad day can be remarkably grim. I was blown from one lane to another one night on the Bay Bridge. Just your basic "whoosh" and you're going down the road another 12 feet to your left. One of the women who worked for us had the steering wheel come off in her hand while doing an off-ramp in Oakland. A bike messenger tangled with a Muni bus and lost; he didn't die though, the driver felt it going over his bike and stopped. The boss saw it happen, picked him up out of the gutter, ascertained that he was unhurt, bought him a drink and fired him. He was lucky. So was Tim, who came in one day quite pale, and sat shaking for a while before explaining that his front tire had been caught in the cablecar slot while descending California Street. He couldn’t slow down much—fortunately a car saw him coming, and got out of the way! (un milagro!) Tim paused and said "You could get hurt doing this... "

It was interesting meeting other messengers—the bikers have the toughest job and the most style. The howling biker, topped with a beanie with a propeller, was one of my favorites. I always wondered about this heavyset middle aged guy in a quasi-military uniform who pedaled a three-wheeler and was always unfriendly. I was later told that he had been in the USAF and had flown too high without an oxygen mask and was not so good as a pilot after that.

I got to know a few people from other companies whose schedules overlapped with mine. I fell in love with some—Mary, whom I met at the airport on Wednesday evenings, who had a bad attitude; and Claire, a pretty night supe at APL—a reasonable, friendly person. There were mail drivers and other drivers that I met daily. Most of the people that I got to know were underlings like me. Clerks, secretaries, mailroom types, drivers and guards. Most of them were OK to work with—they had job to do, knew it and weren't trying to mess you up. One exception was this fat night supervisor (Brenda at APL) who interpreted a schedule that said "No later than 9:30 pm" as meaning no earlier than 9:30 pm. I eventually got a deal worked out with the big bad Brenda which left me departing at 9:00. It was the last stop in a long day and I can assure that the personnel at EDS didn't give a rat's ass. There were inevitable problems: mechanical breakdowns (rare); screwups on actually getting a vehicle, or getting one with no frills (one with windows and a radio rated very high); impossible stops jammed into your route; cab drivers (they run on oil and gas, serve money, and have to do the stupidest things); pugnacious idiots, for whom I carried a tire iron under the front seat: I only had to wave it a couple of times.

Two incidents of idiocy stand out. In Oakland as I was about to make a right turn on a crowded street this clown in a white caddy stopped at the corner ahead of me let his friend out. People honked. As he eased forward, still talking to his friend, I passed him, Flipping the Famous Finger. About four blocks later he pulled up next to me. He leaned over and shouted some shit about "You can't talk to me like that you fuckin' bastard" and then hurled his Coke at me: He hit the inside of his car, splashing sugary treacle shit all over his nice white caddy. The light changed and I drove on, laughing so hard that I couldn't breathe. Dumb fucker.

The second incident was not as funny since somebody got hurt. As I was pounding down Battery one night, I was delayed by this guy driving down the middle of two lanes at about 9 mph. I flashed my lights, honked, and applied cheerful anglo-saxon expletives to his wretched ancestors. When I passed him he of course speeded up to prevent it. Since I didn't drive my own car I didn't care and jammed on past. At the next light he roared up on my left and leaned past his female friend and started cussing me. I laughed at his posturing, clownish machismo, so he pulled a knife and waved it at me. He then dropped it into the leg of his companion, who, screamed. The light changed and I drove on, shaking my head at the idiot Americans. Why do they act this way? I know my story—a tight schedule and an asshole boss who wouldn't take 'no' for an answer; if I didn't make it on time I'm fired. What is the problem with these gringos? Cab drivers are driven to it by their cargo; 'civilians' don't have any such excuse.

There were also abuses that weren't inevitable. Cop stupidity for one. There was a fair amount of that. Abrupt changes in my schedule were often not welcome. If an office moved and they left the stop in your route you could be really screwed—halfway across town, one way streets, no parking. Yet all of the patrones seemed to think that everything could stay the same. They would be hurt if you questioned their wisdom. They would fire you if you persisted in questioning them.

Inevitably, we thought of ways to fight back. In a job of enforced isolation, our methods tended toward the solo. We had talked a few times about strikes, but it wouldn't work; not if it was just our company alone. The patron would just hire temps from some other company, do some of it on his own, and to hell with us. We could be easily replaced—"Can you drive? You're hired!" lf we could get others not to replace us... But there was no easy way; too hard to make contact given the job structure and the transient nature of the workers.

We talked once about on-the-job action. The simplest would be for everybody to obey the law. This was driven home one day when the boss gave us a big lecture about being legal (with routes that required you to go the wrong way on one-way streets). Later I saw him in his three-piece on a moped, speeding the wrong way down a one-way street. If I obeyed the speed limit, never made those quick dashes, my route would have taken twice as long. An effective slowdown could still get us fired.

I found a minor release in a childish game. It started innocently enough; I had to sign for each chunk of computer output at EDS, but nobody cared unless it was checks or something. So one day I wrote "Washington Irving," and later, for variety, "Irving Washington." Soon I was completely out of control—I blush to admit that I signed the names of many of the best and brightest; General Wastemoreland, Lt. Calley, Elmo Zumwalt, Capt. Ernest Medina, Allen Dulles, etc. It all came to an end one day when the mailroom supe in Oakland said, "Primo, your name isn't McGeorge Bundy. Who is he?" A brief lesson on the roots of the Viet Nam war followed, and I was solemnly warned not to do it again. I think I convinced them that I was a little bit strange.

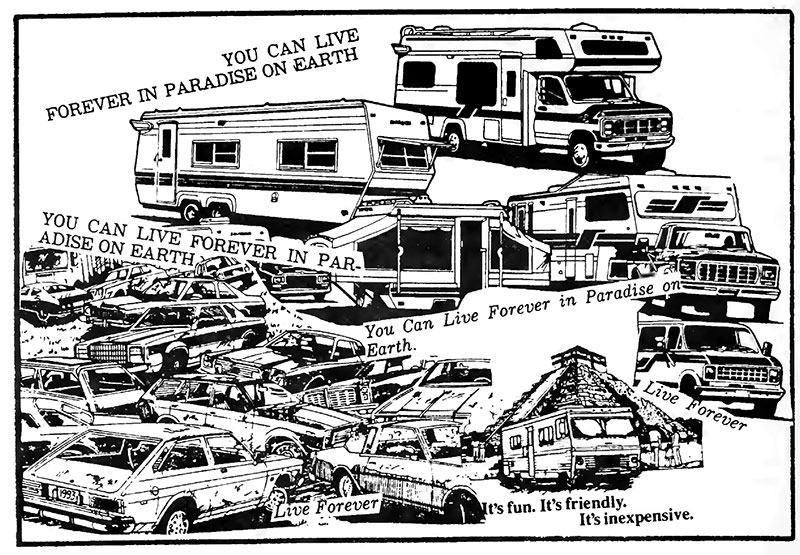

Collage by Cargo Cultists

There was also sabotage.

Some of it was pure self-defense; papers that couldn't be found didn't have to be delivered. There was not a lot of that. There were also cases where bikes or vehicles were incapacitated, and of course the old standards—long breaks or calling in sick. There was some thievery, but not much. Mostly we didn't carry anything worth anything to anybody. US Customs generates an enormous amount of verbal garbage.

My first act involved a shipment of tear gas, gas guns and some training rounds being shipped to West Germany. Because I had friends in that far-off land I was kept informed of the anti-nuclear struggle and its massive absorption of CN gas. The papers were somehow lost, but all I had were duplicates of stuff; I slowed it up but I couldn't stop it. I did handle stuff every day that I regarded as questionable: documents to the free lands of Korea, weird tariff agreements from GATT, internal documents on the stability of such countries as Iran. All these, and more, I did deliver correctly and on time. But one day I was pawing swiftly through the bundle for my airport run when my eye was caught by the destination of one pile—Director, Servicios de Inteligencia; Ejercito de Argentina. In my hand was a fat wad of papers—original AWB (Air Way Bill), a letter of credit and extension, the customs export clearances (with State Department approval), truckers way bill (original), import documents, etc. The whole enchilada, all originals, for a microfiche machine being sent to the Army of Argentina's Intelligence Service. This was in ’76-77 and the dirty war, which the mass media here only reported on years later, was in full swing. The desaparecidos, the dead and maimed, the secret jails, the suffocating terror... And the bastards wanted me to help ship them this high-tech little wonder that would let them catalogue hordes of people in one convenient place. If I had had appropriately dressed friends and a truck, I could've taken the little gizmo home with me (the person who has the originals is the de-facto owner). Instead the papers somehow got lost, and I'm sure the damned thing sat on somebody's loading dock for a long time; to reissue all those papers I took, every single step would have to be retaken. They probably concluded, eventually, that it was "enemy action." Suck on it, you bloody little momios; a clerk who loses papers can hurt you as much as a mechanic that shorts circuits your toy. In this modern world, without the "paperwork" the thing doesn't move; more effectively halted than if padlocked to an I-Beam.

All you paper pushers out there remember; most, if not all, of it is actually garbage and you could better spend your time in bed or in the garden, but you can hurt them; a little snip here and a dropped digit there...

A few years ago the Federal Reserve Bank changed the form on which the US banks' reserves were reported, and a clerk fucked up and didn't fill out one part of it for a large Eastern bank; the Fed thought the money supply had dropped and so increased the supply of US currency, which of course didn't do what it was supposed to. Enormous problems all because of a piece of paper.

The 'on-the-job' protests could only do so much; they kept some pride but couldn't really change the facts of endless job, going nowhere, with too little money for all the problems. Late one night I passed a Pinto on the bridge—I didn't notice anybody in it but there was a woman nearby at the phone on the side of the bridge. A moment of driving and the rear-view mirror revealed a sheet of almost silken flames against the sky and a silhouette of a burning car that was careening past the Pinto. And then I was out of sight.

A few days later the clowns that controlled my days played a little too fast, a little too loose (too many boxes to go the wrong way on a one way street at noon hour, up a small elevator, etc.). I walked over to the phone and made a call to the office; the patron wasn't in so I talked to a fellow serf.

"Jim, I can't take this shit any longer. I quit. The truck is here at the Blue Cross Building, the keys are in it. Bye.

He wished me luck. I took the elevator down to the basement, ignoring the outraged squawks from the head of the mail room, checked out with the guard (yeah man I quit, can't take their shit anymore, bye) and walked home. Dazed, nervous (no geld, and no recommendation from that boss; hell, he might try to have me run down). A grim feeling, but also a good one. No more, bastards! You've shafted me for the last time. I don't ever have to drive out onto that bridge again.