John Reber: The Man Who Helped Save the Bay by Trying to Destroy It

Historical Essay

by Charles Wollenberg

© 2014 University of California Regents, reprinted with permission from Boom: A Journal of California

John Reber promoting his plan to dam the bay, c. 1950s.

Photo: courtesy Anika Erdmann, Flickr

In 1961 three remarkable women—Kay Kerr, Sylvia McLaughlin, and Ester Gulick— started Save the Bay, a grassroots citizens’ movement to preserve and protect San Francisco Bay. It turned out to be one of the most successful efforts at environmental activism in American history. As University of California, Berkeley geography professor Richard Walker has observed, the movement transformed the popular vision of the bay from a “place of production and circulation of goods and people… of no more aesthetic or spiritual import than today’s freeways” to a “vast scenic, recreational, and ecological open space.” New public policies ended bay fill, promoted the restoration of marshes and wetlands, and opened hundreds of miles of bay shoreline to the public. The bay became “the visual centerpiece of the metropolis, a watery commons for the region, and a source of pride to Bay Area residents.”(1)

Yet the dramatic achievements of the Save the Bay movement in the 1960s would not have been possible without the defeat of the Reber Plan in the 1950s. John Reber’s proposal to build two giant dams to transform most of the San Francisco Bay into two freshwater lakes would have destroyed the estuary as we know it. Had Reber’s dream come true, there would have been no bay to save. The Reber Plan also became a crucial and lasting symbolic inspiration for the movement to save the bay. Although the history of the Save the Bay movement is well documented, the rise and fall of the Reber Plan is less well known today. Almost entirely forgotten is the personal story of John Reber, a remarkable figure in Bay Area history who seemed to combine the ambition of Robert Moses, New York’s larger-than-life master planner, with the personality and personal frustrations of Willy Loman, the tragic hero of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.(2)

When twenty-year-old John Reber came to California from his native Ohio in 1907, he planned to become a teacher. But he couldn’t resist the siren call of show business and instead became an actor, director, and writer. He wrote screenplays for Mack Sennet comedies. (Reber said his method was to write tragedies and then “throw in a couple of custard pies” for laughs.) For two decades, he made a good living writing and directing plays and pageants in communities up and down California. Local service clubs such as the Elks usually sponsored the productions, which featured townspeople in the cast. Reber estimated he staged more than 300 performances in sixty towns and cities with local casts of 100 to 5,000 people. This put him in contact with “all the best people,” influential men and women who might later support his bay plan. Senator and former Governor Hiram Johnson said Reber knew more people than anyone else in California. Reber believed his show business experience prepared him to create his grand plan. “What is master planning but stage managing an area?” he asked. According to Reber, the implementation of the plan would be “the greatest pageant on earth.”(3)

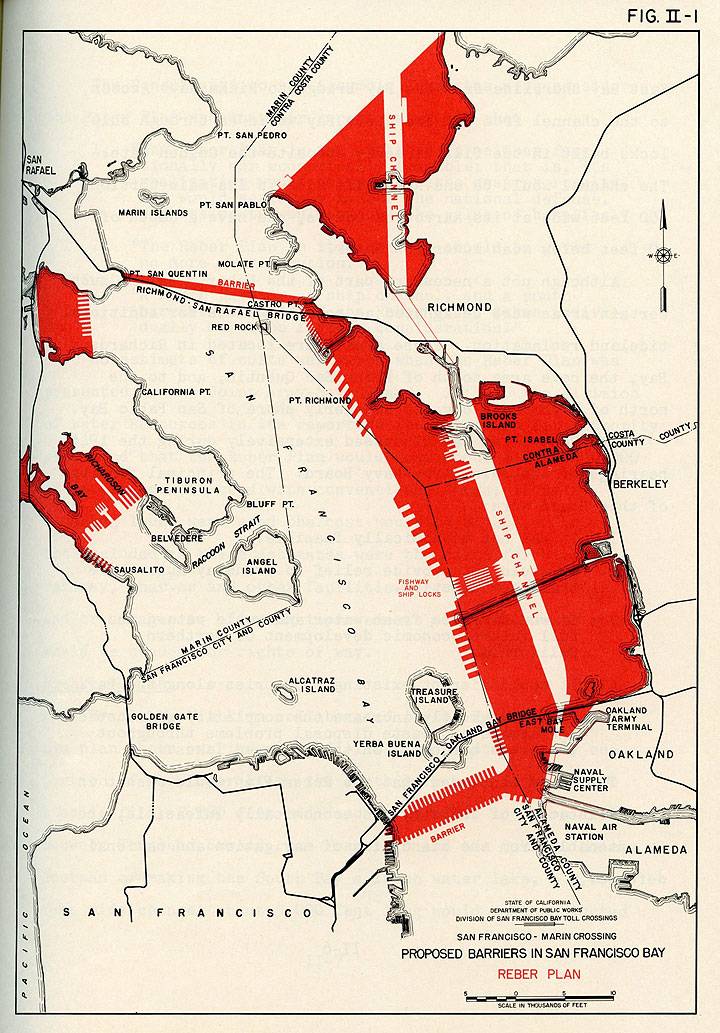

Reber argued the bay was “a geographic mistake,” interfering with the efficient operation of the surrounding metropolis. Because of the bay, the transcontinental railroad ended in Oakland instead of its natural destination, San Francisco. Reber initially favored an earthen causeway to bring the rails directly into the city. But as he traveled around California and learned of the extraordinary value of freshwater to the state’s development, his plan became far more ambitious. By 1929 his proposal included two large earth-filled dams, one located just south of the current Bay Bridge and the other at the approximate location of today’s Richmond-San Rafael Bridge. While the tops of the structures would serve as transportation corridors for rail and auto traffic, the dams would also block saltwater intrusion into both the north and south bays, creating two massive freshwater lakes. Under the Reber Plan, only about 15 percent of the present bay would have remained subject to ocean tides. Reber estimated the lakes would store about 10 million acre-feet of water, more than twice the capacity of Lake Shasta, California’s largest reservoir. The water would have been available for residential and industrial use around the bay and for irrigation in regional agricultural areas such as the Santa Clara Valley.(4)

The Reber Plan also proposed massive amounts of new bay fill, creating about 20,000 acres of additional dry land on what was once wetlands and open water. The largest fill would have been off the Richmond, Berkeley, Albany, and Emeryville shoreline. The plan envisioned a twelve-mile freshwater channel through these new lands, linking the two lakes and allowing runoff from the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers to circulate in both the north and south waterways. The plan included locks to allow shipping to pass from salt water to freshwater. Reber added features as time went on: additional port facilities, an aqueduct to transport water to the San Joaquin Valley, an airport, a regional transportation terminal, and a high-speed military freeway connecting the Bay Area to Los Angeles. As World War II approached, Reber planned new military elements, including naval bases on filled land along the Marin County shoreline and secure hangars and fuel storage facilities in caves created by the excavation of fill for construction of the earthen dams. Later Reber promoted the proposed transportation corridors as evacuation routes in the event of atomic attack.5 During its nearly thirty years of design and debate, the Reber Plan was an organic document, changing to reflect new circumstances and political realities. But the transportation links and the freshwater lakes remained the key elements of John Reber’s grand vision.

Map showing the Reber Plan, a post-World War II proposal.

Thanks to Eric Fischer for making this image, and many more, all in high resolution, available at his flickr account.

Reber belonged to a generation of Americans who had great faith in massive public works. Beginning with the construction of the transcontinental railroad, an enterprise heavily subsidized by the federal government, such projects dramatically affected California’s economic and social development. As early as the 1880s, state engineers studied the concept of saltwater barriers on San Francisco Bay, and in the early twentieth century, a barrier at Carquinez Strait was championed by Contra Costa County business interests concerned about high saltwater content that interfered with industrial processes. Contra Costa industrialists eventually formed the Salt Water Barrier Association to lobby state officials. But by the early 1930s, state engineers had convinced Contra Costa County that the solution to its problem was not a saltwater barrier, but a vast state water project that included high upstream dams on the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, combined with freshwater pumped from the delta.(6) In 1933, California voters approved a bond issue to support the proposal. When the Depression made it difficult for the state to sell the bonds, Washington, D.C. took control of what became the federal Central Valley Project.

Reber initially proposed his plan in the inauspicious year of 1929. Not only was 1929 the beginning of the Great Depression, it coincided with the state engineers’ decision to reject barriers as a solution for Bay Area water problems. In addition, Reber’s plan surfaced as both San Francisco and the East Bay were building public aqueducts to bring Sierra Nevada water to Bay Area cities. Reber’s transportation proposals were upstaged by construction of the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges. Yet in an age of great public works projects that routinely transformed natural systems, Reber’s plan continued to attract attention and support. In 1933, a prominent member of the Elks Club arranged a meeting between Reber and former president Herbert Hoover, who had returned to Stanford University after being defeated for reelection by Franklin Roosevelt. A world-class engineer before going into politics, Hoover proclaimed the Reber Plan “the most complete proposal for the bay.” Hoover’s endorsement gave the project significant credibility and publicity. In 1935, Reber retired from show business to promote the plan full-time. In 1940, he put a model of the proposal on display at the world’s fair on Treasure Island, giving his grand scheme unparalleled public exposure. By 1940, then, the Reber Plan was well launched. For the next two decades it was a matter of intense discussion and debate in the Bay Area, Sacramento, and even Washington, D.C.(7)

Reber devoted the last twenty-five years of his life to promoting his dream. He had little interest in personal wealth. Supported by savings and contributions from his entourage of “Reberites,” he and his wife lived frugally in a modest San Francisco home. He had almost no staff support, turning out a vast amount of correspondence and other paperwork on his home typewriter. Reber was an unusually friendly man, almost always on a first-name basis with supporters and opponents alike. He loved public attention and was willing to talk to any audience, from local garden clubs, service groups, church gatherings, and chambers of commerce, to statewide meetings of business, labor, and farm organizations. Over the course of more than two decades, he claimed to have given more than a thousand speeches on behalf of the plan. He’d arrive at such events with an impressive array of maps and charts and would lace his presentations with homespun humor. His appearances before legislative committees were often tours de force, with Reber the performer dominating the session.(8)

But for all his public relations skills, John Reber desperately needed technical credibility. Although he studied the dozens of scholarly papers and reports that seemed to fill every available tabletop in his home, Reber was a high school graduate with no formal engineering training. His ability to gain the support of professional engineers was crucial to his success. Herbert Hoover was the first but not the last of such supporters. Philip G. Bruton, a retired general from the Army Corps of Engineers, became one of Reber’s strongest advocates. Probably the most important of Reber’s supporting engineers was Leon H. Nishkian. A graduate of UC Berkeley, Nishkian headed a distinguished San Francisco engineering firm that participated in many of the state’s most important construction projects. Beginning in 1940, he worked diligently and without compensation on behalf of the Reber Plan. He prepared engineering schematics and illustrations and came up with a highly favorable cost/benefit analysis. Nishkian submitted written testimony to government agencies and lent his considerable professional reputation to the cause. Due at least in part to Nishkian’s influence, The California Engineer, a respected professional journal, concluded that “competent engineers have examined the project closely and feel that it is entirely feasible.” According to Reber, Nishkian’s untimely death in 1947 was “the blow of blows.”(9)

San Francisco business and political forces were among the powerful interests that rallied behind the plan, believing it would have provided increased regional transportation access to the city’s downtown and, in theory at least, an unlimited supply of freshwater. The central waterfront, the heart of the city’s commercial port, would have remained open to salt water with easy access to the Golden Gate, the only Bay Area port facility with this advantage under the Reber Plan. In 1942, the city’s board of supervisors formally supported the plan, a position enthusiastically backed by Mayor Angelo Rossi. San Francisco’s legislative representatives, including influential assemblyman Thomas Maloney, lobbied for the proposal in Sacramento. Much of the city’s press, particularly the San Francisco Chronicle, also supported the Reber Plan.(10)

But Oakland and most of the East Bay took a very different position. The Port of Oakland had grown steadily in the 1920s and 1930s, but under the Reber Plan, Oakland’s harbor would have been isolated behind a dam. Oceangoing vessels would have had access only through locks located on the filled land off the Berkeley waterfront. (Much the same was true for the ports of Richmond, Stockton, and Sacramento located behind the northern dam.) Irving Kahn, a prominent Oakland retailer and president of the city’s Downtown Property Association, condemned the Reber Plan as “Hitler Tactics,” a plot by San Francisco to keep Oakland in an inferior competitive position “just because you are bigger than we are.” Both the Oakland City Council and Alameda County Board of Supervisors opposed the plan. James McElroy, president of the Oakland port commission, argued the plan would destroy maritime activity in the East Bay. “There is no reason,” he said, “for taking the bay and chopping it into a pond.”(11)

California farmers were among the Reber Plan’s strongest supporters. The state’s Farm Bureau Federation backed the proposal, and its Bay Area affiliates, such as the Santa Clara County Farm Bureau, were especially enthusiastic. Santa Clara Valley fruit and vegetable growers, like many Bay Area and Central Valley farmers, expected to gain access to cheap irrigation water pumped from the new lakes. One of Reber’s most enthusiastic backers was John E. Pickett, editor of The California Farmer and The Pacific Rural Press, two San Francisco–based publications with substantial agribusiness readership. The California Farmer became “a rabid oracle of Reberism,” while the Rural Press referred to the plan as “the greatest project ever conceived.” Pickett eventually became president of the San Francisco Bay Project, a nonprofit corporation established to provide John Reber with financial and organizational support. However, agricultural backing was not unanimous. Many delta farmers feared that during intense winter storms the water backed up behind the northern dam would overwhelm delta levies and flood the region’s fields.(12)

Reber hoped that World War II would increase support for his proposal. He added significant military infrastructure to the plan and argued that the new lakes would provide a secure water supply in case of attack. But Rear Admiral John W. Greenslade, commandant of the Twelfth Naval District, pointed out that the plan would put most of the Bay Area’s naval installations, including the Alameda Naval Air Station and the Mare Island and Hunters Point Naval Shipyards, in freshwater lakes behind the dams. Ships would have to pass through locks, causing “delay and risk to every vessel including danger of a complete blockade.” Admiral Greenslade concluded the Reber Plan “has no merit.”

Reber simply dismissed this, as he did virtually every other criticism. “We are not interested in people unable to grasp what we are driving at,” he said. “We don’t argue with people who are against us, because we know they will be with us eventually.” With Greenslade, at least, that turned out to be the case. After the admiral retired at the end of the war, he had an extraordinary change of heart and became one of Reber’s most prestigious supporters. However, this changed neither the Navy’s nor the Army’s official opposition to the.plan.(13)

The establishment of a “Joint Army-Navy Board on Additional Crossing of San Francisco Bay” in 1946 gave the Reberites another chance to gain military support. Only a decade old, the Bay Bridge already was experiencing traffic jams. Any new bridge or other trans-bay link required military approval. Reber offered his proposed south bay dam as an obvious answer. Designed to be 2,000 feet wide, it could accommodate thirty-two lanes of auto traffic, in addition to both transcontinental and interurban rail lines. Reber and Nishkian called for the board to approve at least the southern portion of the Reber Plan as part of the solution to the region’s transportation problems.

But after the war, the state of California turned against the Reber Plan, as momentum turned toward a major water project in the Central Valley. State Engineer Edward Hyatt and chairman A.M. Barton of the State Board of Reclamation both testified against the Reber/Nishkian proposal. Carl Schedler, a distinguished consulting engineer who had once been the president of the Contra Costa County Salt Water Barrier Association, also emerged as a formidable opponent. He challenged Nishkian’s optimistic financial projections and argued the plan posed a threat to delta agriculture. While the Army-Navy Board finally concluded that additional bay crossings were needed, it went out of its way to reject the Reber Plan. According to the board, Reber’s proposal “would result in a dislocation of industry, is considered economically unfeasible, and further is untenable from the standpoint of navigation and national interests.”(14)

If opponents thought that this strong language would deter Reber and his supporters, they were mistaken. In 1949 California Senator Sheridan Downey brought a subcommittee of the US Senate Committee on Public Works to San Francisco to hold public hearings on Reber’s proposal. Downey was sympathetic to the plan, and supporters outnumbered opponents five-to-one on the list of witnesses. John Reber was the first to testify, entertaining the room for more than two hours in response to Downey’s friendly questions. Emphasizing the importance of hydraulic planning, Reber claimed “there was only one man who could live without water and that was W.C. Fields.” When a senator corrected one of Reber’s many biblical quotations, Reber replied, “I do the work and Mrs. Reber does the praying.” After making his usual strong pitch for the transportation and water elements of the plan, Reber discussed the recreational aspects, promising shoreline parks and “the greatest fishing hole in the world.” He admitted the plan might threaten the bay’s sturgeon fishery, but said “if we can get on friendly terms with Stalin…we can get a few eggs from the Volga River and replenish our supply.”(15)

After Reber’s testimony, San Francisco Bay Project president John Pickett orchestrated the appearance of dozens of additional supporting witnesses, including San Francisco Recreation Department director Josephine Randall, who strongly commended the plan’s recreational components.(16) But opponents, though seriously outnumbered, also had their say. Glen Woodruff, an engineer representing Oakland, said the plan would put his city “at a very decided disadvantage competitively.” State Engineer Hyatt repeated his agency’s opposition, and for the first time was joined by representatives of the federal Bureau of Reclamation. Both state and federal witnesses argued that proper management and expansion of the Central Valley Project would secure California’s water future far better than the Reber Plan. Carl Schedler listed a number of technical difficulties, among them the possibility that there would not be enough freshwater to keep the lakes full during the dry summer months. If lake level fell substantially below that of the remaining bay, operation of the locks would dump salt water back into the lakes. The Bureau of Reclamation feared that that the Central Valley Project would be required to divert water from farms and cities to keep the lakes above the saltwater level of the bay. In effect, the opponents argued the plan would create rather than alleviate a water shortage. Nevertheless, the subcommittee concluded that the proposal had promise and deserved further research. In 1950, Congress appropriated $2.5 million to support a comprehensive Army Corps of Engineers study of the Reber Plan.(17)

The Bay Model, now restored and open to the public as part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

Photo Chris Carlsson

The Corps took thirteen years to complete the study, due in part to delays caused by the Korean War and other priorities. But the congressional appropriation was a victory for Reber and his supporters, and it attracted national attention. In November 1950, The Saturday Evening Post, the nation’s most popular weekly magazine, featured an article on the plan, comparing it in scope to Hoover Dam. The author, Frank J. Taylor, said that because of Reber’s advocacy, the proposal had gone from “a harebrained idea to a project backed by an impressive array of engineering brains.” Taylor described “Old Reber,” then sixty-two-years-old, as a compact, blue-eyed man in perpetual motion. He was “spry as a cricket,” “nimble as a goat,” “bouncing from office to office, to meetings, to public hearings,” always selling his plan. The article closed with Reber’s prediction: “We could be pumping freshwater out of the bay in two years.”(18)

In many respects, the Saturday Evening Post article was the high-water mark for the Reber Plan. Over the next five years, various agencies and branches of state government issued studies that were uniformly critical of the proposal. In 1949, the Assembly Committee on Tidelands Reclamation and Development commissioned John Savage, a well-regarded Denver engineer, to carry out the first independent professional study of the plan. Savage’s findings, released in 1951, were devastating. He confirmed that there was not enough water to keep the lakes full in the summer and too much water to avoid delta flooding in the winter. He also found that the lakes would become seriously polluted, particularly in the dry summer months. Savage pointed out that the Reber Plan would destroy several bay industries, including salt production and commercial fishing. He concluded that the plan was physically possible but “neither functionally nor economically feasible.” Savage’s conclusions were supported by the report of Cornelius Biemond, the water director of metropolitan Amsterdam, who was commissioned by the state legislature to study California’s hydraulic problems in 1953. Biemond estimated the true cost of the Reber Plan was $1.4 billion, not the $250 million figure used by Reber. In 1955, a state board of consultants, composed of five experienced engineers, said that while the Reber Plan “intended to foster industrial expansion, it would actually be most disruptive…. It would transform a great natural harbor into an artificial bottleneck.”(19)

The San Francisco Chronicle reported that John Reber took these setbacks “with a smile.” He replied at length to the critical reports in the newspaper’s This World weekly magazine. But instead of directly countering most of the technical points contained in the reports, Reber simply repeated the familiar arguments that he had been making for more than two decades. In effect, he claimed that the technical criticisms could not be valid because the plan was endorsed by distinguished engineers such as the late Leon Nishkian. Reber concluded that his plan was “a must” if the Bay Area was to increase its regional population from the current three million to a projected twenty-one million in the twenty-first century. A Chronicle editorial argued that the state reports should not be accepted as the last word, but the newspaper’s editors admitted the documents had an “impressive air of finality.”(20)

In fact, the plan never recovered from the combined impact of the state studies. By the mid-1950s, Reber was in poor health, suffering from severe asthma. But he gamely carried on, maintaining his public optimism. After one hospital visit, he told reporters, “I had a talk with the Lord. He told me I have five more years. And I’ m going to see the start of construction on the Reber Plan.” But it was not to be. On 16 October 1960, John Reber died at the age of 73. The Chronicle and the San Francisco Examiner covered his death as a front page story. Even the New York Times printed a substantial obituary.(21)

During the last years of his life, Reber and his supporters pinned their remaining hopes on the much-delayed Army Corps of Engineers study. If it found the Reber Plan desirable and viable, they thought, the study would more than offset the damaging conclusions of the previous state reports. In 1957, the Corps built a giant hydraulic bay model on the Sausalito waterfront to study the proposal. It covered an acre and a half and was located in a large building that had once been the warehouse of Marinship, a World War II era shipyard. In 1960, researchers began running simulations of the Reber Plan on the model. The results confirmed some of the most discouraging findings of the state studies. The Corps of Engineers research report, published in 1963, concluded that the plan was “infeasible by any frame of reference.”(22) This was the final nail in the coffin. The Reber Plan was dead, laid to rest three years after the passing of John Reber himself.

The Reber Plan was not killed by environmental opposition. It was defeated by the powerful interests it threatened and experts who believed it wouldn’t work. Neither the San Francisco–based Sierra Club nor any other mainline conservation organization took a position on Reber’s proposal. When the Save the Bay campaign began in 1961, Sierra Club executive director David Brower said his organization had other priorities. Preservation of pristine wilderness was more important than saving a gritty waterway surrounded by a heavily populated metropolitan region. The established conservation groups became actively involved only after Save the Bay generated considerable popular support. In 1965, just two years after the final defeat of the Reber Plan, the California legislature passed the McAteer Petris Act, establishing the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC). The new agency had authority to regulate land use along the bayshore and establish a plan to guide future bay conservation and development policy. Four years later, Governor Ronald Reagan signed legislation approving BCDC’s permanent Bay Plan, a document that included powerful environmental protections for the estuary.(23)

The establishment of BCDC and the approval of its ambitious plan were major victories for the Save the Bay movement. That movement was in turn a reflection of the new environmental consciousness that was part of the larger process of social and cultural change in the sixties. Save the Bay, initially an effort to protect the estuary from further land fill, evolved into a broad campaign to preserve and restore San Francisco Bay as a natural ecosystem. By contrast, the effort to defeat the Reber Plan was part of an argument over how best to use and exploit San Francisco Bay as a natural resource. If the Reber Plan had succeeded, there would have been no bay to preserve. The engineers, business leaders, military officers, bureaucrats, and politicians who opposed the Reber Plan made the subsequent Save the Bay movement possible. Without realizing it, they were Act I in the play to save the bay, an act that paved the way for a cultural re-envisioning of the bay that was as dramatic in its own terms as the physical transformation proposed by John Reber. While Reber’s dream is long dead, and the Reber Plan only resurfaces from time to time as a symbol of what might have been, the dreams and aspirations of the Save the Bay activists thrived and remain powerful today.

Saving the Bay from “the Future”!

From the weird madness of the Reber Plan to dam both ends of the Bay into freshwater lakes in the 1950s to the Save the Bay movement of the early 1960s that helped create the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, we’ve come a long way in a half century. Today’s open shorelines, closed trash dumps, and returning wetlands honor and preserve our greatest public resource. Historian Chuck Wollenberg and Steve Goldbeck from BCDC.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/SavingTheBayFromTheFutureMarch282018_201803" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Video: Shaping San Francisco Public Talk March 28, 2018

Notes

1 Richard A. Walker, The Country in the City: the Greening of the San Francisco Bay Area (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007), 110–111.

2 Matthew Morse Booker says the Reber Plan “could have been perhaps the greatest calamity ever to befall the bay.” Down by the Bay: San Francisco’s History Between the Tides (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 219.

3 San Francisco Chronicle, 17 October 1960; San Francisco Examiner, 17 October 1960; Frank J. Taylor, “They Want to Rebuild the Bay,” Saturday Evening Post, 18 November 1950, 32–33.

4John Reber, “San Francisco Bay Project—the Reber Plan,” Leon Nishkian Papers re: the Reber Plan, (hereafter cited as Nishkian Papers), box 2:2; David R. Long, “Mistaken Identity: Putting the John Reber Plan for the San Francisco Bay Area into Historical Context,” American Cities and Towns: Historical Perspective, Joseph F. Bishel, ed. (Pittsburgh: Dusquense University Press, 1992), 129–130; Philip J. Dreyfus, Our Better Nature: Environment and the Making of San Francisco (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), 152.

5 W. Turrentine Jackson and Alan M. Paterson, The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta: The Evolution and Implementation of Water Policy (Davis: California Water Resources Center, 1977), 63–65; Dreyfus, 155.

6 Alan M. Paterson, “The Great Fresh Water Panacea: Salt Water Barrier Proposals for San Francisco Bay,” Arizona and the West (Winter 1980), 308–314.

7 Catherine Way, “Reber’s Dam Folly,” California Living Magazine, San Francisco Chronicle/Examiner, 29 July 1984, 18; Paterson, 317; Dreyfus, 155.

8 Taylor, 33, 156; Jackson and Paterson, 65.

9 Dan Cameron, “The Reber Plan,” California Engineer (December 1947), 8–9, 26; Dreyfus, 157–158; Jackson and Paterson, 67; Nishkian to Roger Lapham, mayor of San Francisco, 25 October 1944; Nishkian to Honorable Earl Warren, 4 December 1946; Nishkian to R.S. Clelland, Acting Regional Director US Bureau of Reclamation, 10 October 1945, Nishkian Papers, box 1:2.

10 Chronicle, 17 August 1946; Paterson, 317; Dreyfus, 155.

11 Chronicle, 25 April 1942; Oakland Tribune, 25 April 1942.

12 California Farmer, 5 April 1952; Pacific Rural Press, 27 September 1947; Jackson and Paterson, 65; Dreyfus, 156.

13 District Staff Headquarters 12th Naval District to Board of Supervisors City and County of San Francisco, 1942, Nishkian Papers, box 1:2; Taylor, 158; Dreyfus, 156–157.

14 L.H. Nishkian, “Report on the Reber Plan and Bay Land Crossing to the Joint Army-Navy Board, “ 12–15 August 1946, Nishkian Papers, box 2:1; “Report of Joint Army-Navy Board on Additional Crossing of San Francisco Bay” (Presidio of San Francisco, 1947), 5–6, 57, 68–81.

15 Needs of the San Francisco Bay Area, California, Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Public Works, United State Senate, December 8–16, 1949 (hereafter cited as Hearings) (Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1950), 4–33; Taylor, 156.

16 Hearings, 42–106.

17 Hearings, 164–232, 240–255; C.W. Schedler, “Comments on the Reber Plan Prepared for Senator Downey at the Hearings of the Public Works Committee,” (San Francisco, 1949), 1–24.

18 Taylor, 32–34, 156–158.

19 California State Assembly, First Report of the Interim Fact-Finding Committee on Tideland Reclamation and Development in Northern California, Related to Traffic Problem and Relief of Congestion on Transbay Crossings (Sacramento, 1949), 23–25, 27; John L. Savage, Report on Development of the San Francisco Bay Region (San Francisco, 1951), 1–2, 24–78; Jackson and Paterson, 67–69.

20 Chronicle, 30 March 1955, 31 March 1955, 29 May 1955.

21 Chronicle, 17 October 1960; Examiner, 17 October 1960; New York Times, 17 October 1960.

22 US Army Engineer District San Francisco, Comprehensive Survey of San Francisco Bay and Tributaries Technical Report on Barriers, (San Francisco, 1963); Way, 19; Dreyfus, 163. In this era of computer simulations, the Bay Model is no longer used for research, but the Corps of Engineers still operates it for educational purposes with an attractive visitor center.

23 Mel Scott, The San Francisco Bay Area, a Metropolis in Perspective (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 315–317; Walker, 113–116; Booker, 165. In 2007, BCDC briefly studied and then rejected the idea of a saltwater barrier at the Golden Gate to protect the bay from sea level rise due to global warming. San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission, “Analysis of a Tidal Barrier at the Golden Gate,” (San Francisco, 2007), 1–10.