Golden Gate Park History

Historical Essay

by Christopher Pollock

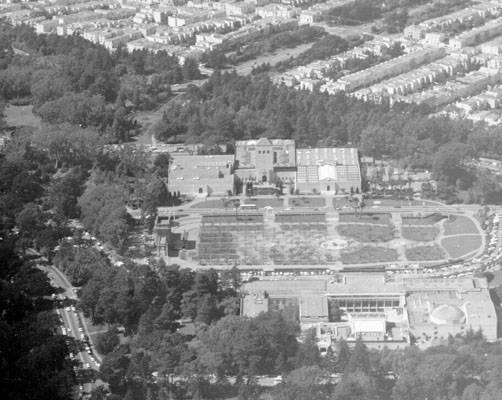

Aerial view of Golden Gate Park looking northwest at the Bandstand, De Young Museum, Steinhart Aquarium, and the Academy of Science, 1970.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Every place has a story to tell, and Golden Gate Park, an icon and keystone of San Francisco's park system, is no exception. Millions of people have visited the park over the years, but only a few know of all the rich nuggets that it harbors. Golden Gate Park offers a dizzying array of treasures: fascinating buildings, scenic meadows and lakes, important monuments, and major museums.

The history of the Golden Gate Park goes back to the 1860s. The Gold Rush and the discovery of the Comstock Lode in the mid-1800s had catapulted San Francisco from a minor port town into a metropolis, buoyed by completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Pioneer Californians were proud of their isolation in the Far West but were also aware of their difference from the established, cultured East Coast. The emerging cosmopolitan city lacked the earmarks of greatness, such as museums, wide tree-lined boulevards, and monumental civic buildings, let alone a great park.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/Mdkp7YBB-zU" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

History of Golden Gate Park

Video: Glenn Lym

With the blossoming of large late 19th century businesses in San Francisco, there emerged a much more dense population. Businesses created jobs and enticed workers to San Francisco, but they also created crowded conditions. Society sought a balance between the urban and natural worlds, and felt a romantic yearning for the simpler past. Everyone could see the need for a remote park to provide an escape from their workaday lives. Parks became an antidote to the materialistic ambitions of the city's citizens.

A quintessential place of outdoor recreation (re-creation), Golden Gate Park would one day be an important piece of San Francisco's infrastructure, a feature that would help make the West Coast city a distinctive metropolitan area. The park's designer, William Hammond Hall, illustrated the independent spirit of the Bay Area when he ignored the advice of Central Park's landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted and created an oasis where Olmsted thought none should be built. San Francisco was also to ignore the Chicago-based Daniel "Make No Little Plans" Burnham's advice to polish the city's image with a grand new street layout, although some aspects of Burnham's thinking, and of Olmsted's, were later incorporated. Just a generation after the overland wagons and seaworthy ships had delivered their cargoes of pioneers to the City by the Bay, the park was, in varying degrees, covered in greenery.

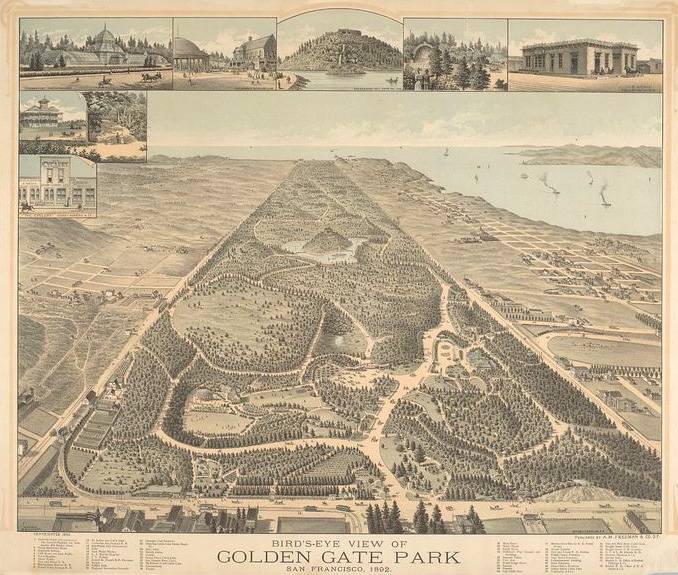

Bird's-eye view of Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, 1892. View from east end of park looking towards Pacific Ocean; seven marginal images at top depicting sites of interest. Legend includes cable lines and railroads.

Few visitors know the story of how the park was created, let alone of the foundation of sand dunes blanketed with trees, shrubbery, and other plants. Seemingly natural oases containing lakes, streams, and waterfalls are cradled within its rolling landscape. Key to creating the verdant appearance of this dry, windy environment has been water. The fact that Golden Gate Park has endured as the playground of the recreation-hungry city is a testament to its visionary founders and hardworking keepers.

The many monuments and buildings constructed in late 19th century San Francisco were meant to project the accomplishments of American civilization. Post-Gold Rush architecture within the park reflects the eclectic tastes of the Victorian period. Some buildings look to past styles, such as Mission Revival, Classical, and Spanish Colonial. Themed buildings redolent of Egypt, Holland, Spain, England, Italy, and other countries were built in neohistorical styles as America was finding its own way stylistically. There were constructions in the rustic taste: bridges across the Chain of Lakes and several shelters using all manners of branches and logs.

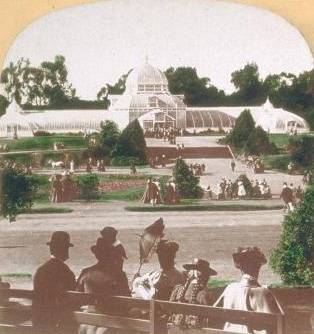

Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, 1897

At the turn of the century, Golden Gate Park was the free Disneyland of its time, with attractions ranging from animals and birds to lush plantings and numerous types of recreational and athletic activities. It was a huge success, despite its location far from where the populace lived. Competition came from other nearby commercial ventures, including the closer-to-downtown Woodward's Gardens in the Mission District (the city's playground-for a fee; 1866-1892); the first Chutes, located on Haight Street between Cole and Clayton Streets (an amusement park; 1895-1902), a second version at Tenth Avenue and Fulton Street (1902-1908), and the final one on Fillmore Street between Turk and Eddy Streets (1909-1911); and several incarnations of Playland-at-the-Beach (1916-1972). Of these places, only the park has held up against the city's hunger for home sites.

Many structures that today contribute to the texture of the park were never planned by its originators, who preferred to keep development to a minimum. Furthermore, like old growth in a forest, many of the park's earliest structures have been replaced by updated versions or removed entirely. In a way, Golden Gate Park is an anachronism, a relic of the Industrial Revolution's pinnacle, the Gilded Age. It echoes many of the major events and figures of any city: the dawn of flight, earthquake and fire, expositions, war, presidential visits, movie stars, politics, moneyed donors, and just plain citizens. In the park's early years, society focused on the idea of progress, and the park's architecture reflected that notion with major innovations in structure. Its texture, interwoven with the names of the city's builders during a time of dynamic change, is a reflection of San Francisco's enterprising characters and evolution into a premiere metropolitan city.

Citizens have recently taken a more active interest in the park's preservation, approving millions of their tax and bond dollars to repair the failing infrastructure. Aging lighting, water delivery, and sewage removal systems are being replaced. Major storms in 1995 did considerable damage to the park, including the historic Conservatory of Flowers, which has been fully restored with public and private funds. Replacement of the DeYoung Museum and rebuilding of the California Academy of Sciences, changes that will dramatically revise the landscape of the park's Music Concourse, have been under consideration for many years and are now moving forward. [Ed. note: The new DeYoung Museum and Academy of Sciences are open as of late 2008.]

Greening of the Outside Lands: The Park's Early History

Today's tapestry of buildings, meadows, lakes, athletic fields, forests, and gardens is far from the original state of the northwest tip of the San Francisco peninsula, for which a more appropriate name would have been "Sand Francisco." Labeled the "Great Sand Bank" on an 1853 map, the sparsely populated and virtually treeless landscape of windswept, rolling dunes gave no hint of the potential for greenery. Naysayers called the park's future location a "dreary desert"; indeed, the chosen spot must have seemed the most undesirable area imaginable to those without a trained sense of landscaping. What was to become Golden Gate Park was an unprecedented horticultural experiment on a vast scale.

Early chronicler Frank Soulé noted in his 1854 Annals of San Francisco, "There seems no provision … for a public park-the true lungs of a large city." Soulé scolded that every square vara (the Spanish unit of measure still in use at the time) was slated for building lots. In addition to Portsmouth Square, San Francisco's original nucleus, only three squares had been planned as recreation space for the town. The three earliest maps of the city--by surveyors Jean-Jacques Vioget (1839), Jasper O'Farrell (1847), and William M. Eddy (1849)--had projected only two additional open spaces: Union Square and Washington Square, both gifts to the city in 1850 from John White Geary, the first mayor of newly American San Francisco. Columbia Square was a third. Later, in 1855, the Western Addition was planned with seven large squares. San Francisco swelled from a population of some 1,000 in 1848 to more than 149,400 by 1870. Rapid growth left little time for planning parks.

During that time, financier William "Billy" Chapman Ralston persuaded the board of supervisors to bring noted East Coast landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted to San Francisco to advise about the possibilities of a grand park on the western section of the peninsula. Olmsted had teamed with architect Calvert Vaux and won a competition in 1858 to create New York's highly successful Central Park. In 1865, San Francisco Mayor Henry Perrin Coon contacted Olmsted about preparing a similar plan for his city, but Olmsted did not believe that such an oasis could be created on the arid Outside Lands. Instead, he proposed a greenbelt (an Olmsted trademark used in several other U.S. cities) that would stretch through the city from Aquatic Park to the vicinity of Duboce Park. He chose sites--especially along Van Ness Avenue--that were sheltered, which he felt was intrinsic to the success of landscaping with native drought-tolerant materials, a visionary idea at that time. The long range concept could be extended into a series of small parks over time. Ultimately, Olmsted's plan was not adopted, because city fathers had hoped for something more like Central Park. Olmsted's ideas did greatly influence the supervisors in their decision to proceed with a park, however.

Acquisition of land for the park was a long, drawn-out matter. When San Francisco petitioned the Board of Land Commissioners for land that was not originally within the city limits, a legal fight ensued to capture the entire west side of the peninsula, bordered by Divisadero Street. Squatters who occupied this desolate area, called the Outside Lands, claimed ownership by possession. Some of these occupants were politically and financially well connected, which helped them stall any movement by the city to claim land they felt they owned as homesteaders. In 1864, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Johnson Field handed down a decree in favor of the city, which an act of Congress confirmed on March 8, 1866. Although these were steps in the right direction, however, neither action settled the issue of specific claims. Mayor-Elect Frank McCoppin finally negotiated a settlement, asking claimants to surrender 10 percent of their holdings and help the city acquire the land once and for all.

In 1868, Mayor McCoppin ordered a survey of potential park sites west of Divisadero Street. The state legislature approved order 800 by San Francisco's board of supervisors, and Governor Henry H. Haight signed the bill on December 7, 1868. A committee appointed by the board of supervisors was given the task to appraise and apportion the land; the 1,013 acres established for the park were valued at $801,593. An April 4, 1870, act of the state legislature set the park's boundaries and proclaimed the inception of Golden Gate Park, which was the first documented use of the name. Shortly thereafter, on April 19, the governor appointed a three-person Board of Park Commissioners. Bonds were sold and bids sought for a survey of the future park, a task carried out by William Hammond Hall.

With the land finally in hand, construction started that fall on the area closest to the city, the Panhandle, at the park's eastern end. The process of reclamation was arduous and long but paid off in the end. Hall was well versed in soil management, though he had to be creative to solve the particular problems associated with converting the park's sometimes shifting sands into a growing medium. To those who argued that the entire park site should be flattened-including one self-serving contractor who coveted the resulting soil as free fill for a project at Mission Bay--Hall recalled Frederick Law Olmsted's advice to capitalize on the "genius of the place" and maintain the site's natural features wherever possible.

The sandy soil posed another challenge when it came time to plant. Lupine (a perennial shrub) was initially planted in the sand dunes but could not take hold fast enough to restrain the blowing sand, especially at the exposed beach areas. Serendipity finally helped: barley grain spilled onto the sand from a horse's feed bag, and Hall noticed later that it had sprouted. The quick-growing seed was broadcast on the sands but lived only a couple of months, not long enough to set deep roots. Next came sea bent grass mixed with yellow lupine. Over this were spread topsoil, manure, and organic matter. By 1873, the drifting sands at the beach had been tamed and further harnessed with a fence made of boards and posts covered with tree boughs and brush. The fence was located about 100 feet from the shoreline and extended across the length of Ocean Beach to barricade the encroaching winds.

In an 1873 report to the park commissioners, Hall deftly noted, "These enterprises are found to pay-to yield to the city a direct moneyed return on her investment." B. E. Lloyd's Lights and Shades in San Francisco notes that just four years after opening, the park, "traversed by promenades, bridle paths and drives, invites the pedestrian, equestrian, or driver to follow their mazy windings into the labyrinths of hedges and borders." Some 15,000 people visited the park that year. By 1876, development had reached Conservatory Valley, despite budget cutbacks.

By the late 1880s, several streetcar lines made the park accessible to all who could afford the fare, boosting its popularity. Railroad tycoon Leland Stanford began conversion of the Market Street Railroad to cable in 1883, increasing the speed and distance of mass transit. The McAllister and Haight Street cable-driven lines brought people to the eastern end of the park for recreation, which in turn made the area a fashionable and sought-after residential district. "Cable, electric, and steam-cars reach the park from all parts of the city," noted an 1892 writer. Nine streetcar lines terminated at the park by 1900, providing ample transportation. By 1902, the automobile was also bringing people to the park, but the newfangled method of transportation was initially banned from the park itself because the fast and noisy machines were believed to frighten horses and bicyclists. Finally, in 1904, cars were admitted into the park through the Page Street Gate, although they remained banned from the Concourse until 1912.

Transformed or not, the arid, sandy environment of the park couldn't sustain plants without a constant supply of fresh water. The Spring Valley Water Company had supplied the park's lifeblood for its first seven years, but water was costly, even at the reduced rate the city paid, and the park commission sought a water supply within the park as early as 1886. The ingenious solution was to drill wells near the salty Pacific Ocean, (the first suitable one in 1888, followed by two others), pumped by windmills.

By the turn-of-the-century, the park was already well under way to becoming a special place when it received another boost: a 1900 city charter reform transferred power from the three-person governor-appointed board to a city and county of San Francisco five-member park commission, providing closer contact with the park's development and the needs of San Francisco.

Tenacious Visionaries: William Hammond Hall and John McLaren

Two men with distinctly different styles share the credit for the creation of Golden Gate Park, namely engineer William Hammond Hall, for the park's framework and initial landscaping, and horticulturist John McLaren, who made the park his personal mission until his death. McLaren's long tenure often overshadows Hall's expertise, but the determined efforts of both men led to what exists today.

William Hammond Hall

Courtesy of Strybing Arboretum

The family of Maryland-born William Hammond Hall (1846-1934) moved to San Francisco in 1853 but relocated to Stockton the next year, following major property losses in one of the city's all-too-common catastrophic fires. "Ham" attended a private academy in Stockton with the intention of attending the military academy at West Point, but with the commencement of the Civil War, his parents revised his plans, and he remained at the academy in Stockton until 1865. His professional civil engineering career started immediately when he apprenticed as a draftsman and surveyor for the U.S. Corps of Engineers. He advanced quickly, among other things surveying the west coast around San Francisco Bay for the U.S. Coast Survey. His efforts with the army allowed him to observe the reclamation of sand dunes along the city's western edge, an important ingredient in his future. With his move to private practice, Hall was on the brink of what would become a renowned, if checkered, career.

On April 19, 1870, Governor Henry H. Haight appointed a three-person Board of Park Commissioners, which soon solicited bids for a topographical survey for a large city park in San Francisco. The 24-year-old Hall won the contract for $4,860 on August 8, 1870, and completed the task, including a preliminary plan, in six months. Hall's prior knowledge of the terrain was an enormous help, as he designed undulating roadways that took advantage of the terrain, kept speeding drivers at bay, and sheltered users from the incessant winds. Appointed superintendent on August 14, 1871, at a salary of $250 a month, Hall met great opposition from naysayers who felt that the Herculean task of turning sand dunes into a verdant park sounded like alchemy.

Later, Hall became a victim of political motivation and revenge by former blacksmith-turned-Assemblyman D. C. Sullivan. Hall had fired Sullivan for padding his bill while in the position of blacksmith, and Sullivan accused Hall of wrongdoing and had him investigated by a special committee. Although none of the charges stuck, Hall resigned in April 1876 when his salary was cut in half. He continued to consult on behalf of the park without compensation and regained an official title when Governor George Stoneman appointed him consulting engineer to the park in 1886; he kept the position until 1889. During this time, he hired and trained John McLaren as assistant superintendent, initially assigning McLaren the job of landscaping the Children's Quarters, designed by Hall.

John Hays McLaren

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Legendary John Hays McLaren (1846-1943) presided over the park as its superintendent for 53 years. Hailing from a farm in Stirling, Scotland, just west of the Firth of Forth, the stocky Scot learned his trade by working on nearby estates from the age of 16. Later he worked in Edinburgh's Royal Botanical Gardens. At age 24, he sailed for America. A short time after arriving on the east coast in 1869, he proceeded to the west coast by ships and by a train across the Isthmus of Panama. Finally settling in San Mateo County, McLaren worked on large estates for 15 years before joining the park. He was employed primarily on the lavish George H. Howard Estate, "El Cerrito," and did work for other notables, such as financier William Chapman Ralston, railroad tycoon Leland Stanford, and banker Darius Ogden Mills. He is responsible for the continuous rows of eucalyptus trees that still line El Camino Real along the peninsula.

Following three years as assistant superintendent, McLaren became superintendent in 1890, overseeing 40 gardeners whose ranks would swell to 400 during his long tenure. Using experience and direct observation, the shrewd and aggressive superintendent worked diligently to keep politics and commercialism out of the park. He was held in great esteem but was also considered hard to work for by some. "Wild game is coming" was the muffled cry when McLaren came to inspect his workers. McLaren's landscaping philosophy was similar to Hall's in that he wanted to create a natural look by working with nature, not against it. He was an experienced horticulturist and forester who studied the local climate and what would thrive in it. Still a dynamo when he reached his 70th birthday in 1916, he was granted a special honor. With McLaren's mandatory retirement at hand, the board of supervisors passed special ordinances giving him lifetime tenure over the park. Blind at the end of his life, he relied on protégé Julius Girod to be his eyes.

McLaren's work was not limited to Golden Gate Park but also included other emerging city parks and special events. He did landscaping for the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition and for the 1939 Golden Gate Exposition on Treasure Island. In appreciation, a special day was set aside at the PPIE to honor McLaren for his design work, and two local newspapers presented him with an engraved loving cup (an ornamental vessel, or award); some 4,000 San Franciscans had contributed as little as a few cents each toward the gift. Other accolades for the indomitable, self-described "Boss Gardener" included the naming of an avenue in the prestigious Seacliff District after him, and the award of an honorary doctorate by the University of California at Berkeley. Upon his 80th birthday and his 40th year with the park, a 450-acre park in the Outer Mission was named after him. McLaren Lodge in Golden Gate Park honors his longtime contributions, and the East Bay's Tilden Park has a meadow named after him.

After his death in 1943, at age 96, McLaren's body lay in state in the San Francisco City Hall Rotunda, a tribute reserved for only a few San Franciscans. Later, the funeral cortege drove his casket through Golden Gate Park, also a special honor, as the park commission normally discouraged corteges from entering the park. His final resting place is, appropriately, the garden cemetery of Cypress Lawn in Colma.

Monuments and Statues: Unwanted by the Park's Makers

"The value of a park consists of its being a park, and not a catch-all for almost anything which misguided people may wish up it," according to the first Golden Gate Park superintendent, William Hammond Hall. Hall considered the park to be a place to enjoy nature without the trappings of the city, a place that did not include a lot of structures, particularly ones that did not contribute to the true park experience. Yet in an 1873 report to park commissioners about the state of the park, Hall noted, "Some classes of park scenery are fitting settings for works of art, such as statues, monuments, and architectural decoration."

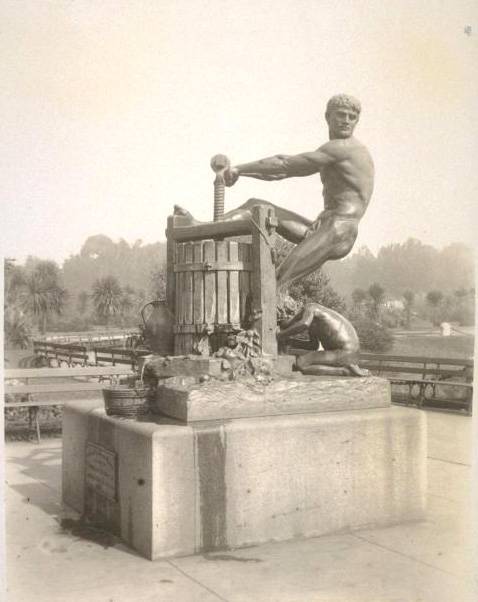

Apple Press Monument: Relic of the Mid-Winter Fair, 1894, still in the same spot, where the new Music Concourse is now, Golden Gate Park, 1898.

Following Superintendent John McLaren had even stronger views, firmly believing that statuary would weaken the goal of creating a pastoral setting. Because of his dislike for the structures, McLaren would commonly plant densely around those that did find their way into the park, letting nature envelop them as quickly as possible. McLaren quipped in his Scots brogue, "Aye, then, we'll plant it ott!" after another "stookie," as he referred to them, was placed.

An 1892 San Francisco Chronicle account notes, however, that the park was "not very well endowed" as monuments go, a clue that the city's society desired these elements. Former Mayor James Duval Phelan, a proponent of the turn-of-the-century City Beautiful movement and president of the Association for Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco (1904-9), donated several pieces to the city over time and encouraged others to do the same. After McLaren's death, with a new administration in the park, the pieces hidden under his reign were rediscovered. Trees and hedges were trimmed to reveal the artworks, and the press made them known to a generation who hadn't seen them before.

Today the park discourages installation of monuments, suggesting instead that donations be directed toward enhancement of the existing park. Monuments reflect the culture of Victorian times, when society felt that the presence of physical tributes distinguished bygone individuals and events and honored the courageous accomplishments of civilization. With posterity in mind, the detailed parts, usually cast of bronze, were combined with larger features of natural hard stone. During an era of imperial expansion by the United States, these physical symbols seemed to enlighten and uplift people and were also status symbols that fulfilled the notion of urban beautification. The point of being newly rich during the fin de siécle Gilded Age, which lasted roughly from 1880 to 1906, was that wealth was to be displayed. Mortality and mourning in the Victorian period were reflections of 19th-century spirituality. In an age when high death rates were common and life spans short, memorials seemed to confer longevity as well as be a visible expression of grief. In the context of the new photographic technology of the time, "secure the shadow or the substance fades" was a prevalent attitude.

In some respects, the park is now an open-air museum of artifacts, a repository of remembrances by moneyed individuals or organizations that sought veneration. While most are on the highly visible Music Concourse, others occur all around the park. They range from donations of a select cadre of powerful rich individuals who would not be forgotten to contributions from first-generation immigrant ethnic groups to denote their growing stature and desire for respect. Still others represent a variety of causes, mostly patriotic. Some simply honor humble citizens for their contributions to society. More subtle monuments abound in the forms of roadways, meadows, waterfalls, and the like, all named after their benefactors or an admired person.

Over time, the park's statues have been relocated like pieces on a game board. The Francis Scott Key Monument has been in three different sites. Douglas Tilden and Willis Polk's 1897 Native Sons Monument, currently located downtown at the intersection of Post, Montgomery, and Market Streets, was in the park's Redwood Memorial Grove from 1948 until 1977, and stood prior to that at the crossroads of Mason and Turk Streets. The Goethe and Schiller Monument and the Goddess of the Forest, Doré Vase, and Thomas Starr King statues have each been moved to suit the purposes of the times. Some statues, including the original Sarah B. Cooper child statue, the fountain in front of the Conservatory of Flowers, and the marble bust of Ruben H. Lloyd at Lloyd Lake, are gone entirely.

On the cusp of the World War I Armistice in 1918, San Francisco Mayor James Rolph received a letter from a correspondent who signed himself "Patriot" and said that he found the Goethe and Schiller Monument objectionable. The writer stated in the San Francisco Chronicle of June 13, 1918, that the statue to "a pair of Huns" should be melted down and recast as a Joan of Arc tribute. Patriotic fervor again reared its head just after the war, on May 8, 1919, when the San Francisco District of the California Federation of Women's Clubs passed a resolution to request that any future monuments added to the park be of "Illustrious Americans."

Some ideas have never made it off the drawing board but have remained a concept in the artist's head or to be located elsewhere. In 1998, for example, San Francisco Art Commission President Stanlee Gatti proposed that a 24-foot-high stainless steel peace sign be located in the Panhandle. The work of sculptor Tony Labat was intended to commemorate the hippie days of the Haight-Ashbury District, but area residents objected, claiming it would draw a bad element. In 1897, Mayor James Phelan commissioned artist Douglas Tilden to create a monument to explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa to be placed at the western end of the park looking out over the Pacific. The model was made but never cast because of the untimely outbreak of the Spanish-American War on April 21, 1898. At other times, simple budgetary problems have prevented perfectly uncontroversial monuments from being built. The Scandinavian Civic League proposed a heroic-size statue of Leif Eriksson in 1936, for example, but nothing came of the Depression-era proposal.

The San Francisco Art Commission has joined forces with the Recreation and Park Department to establish the Adopt-a-Monument Program to raise funds specifically for the restoration and maintenance of the city's monuments. Only one within the park--General John Joseph Pershing-- has its own endowment fund.

Animals and Birds in the Park

Over time, a kaleidoscope of captive creatures has inhabited the park. Only the bison remain today, but the menagerie in the past included deer, elk, moose, caribou, and antelope. At one time, donkeys and goats gave rides to children, while chickens inhabited an imitation barnyard, both located in the Children's Playground. More exotic specimens have included elephant, zebra, bear, kangaroo, emu, and ostrich. A spectrum of smaller unusual birds, including pheasants of many types, peacock, and quail, were all at one time part of the park landscape. In February 1927, Park Superintendent John McLaren suggested that the city find a better-suited site to create a zoo, and in 1929, the animals became part of the nucleus of the San Francisco Zoological Gardens, a project of Park Commissioner President Herbert Fleishhacker. The zoo's connection still remains: Golden Gate Park's eucalyptus trees supply tender leaves to feed the zoo's koala bears.