Chinese Americans in San Francisco during World War II

Historical Essay

by Yifan Huang, 2015

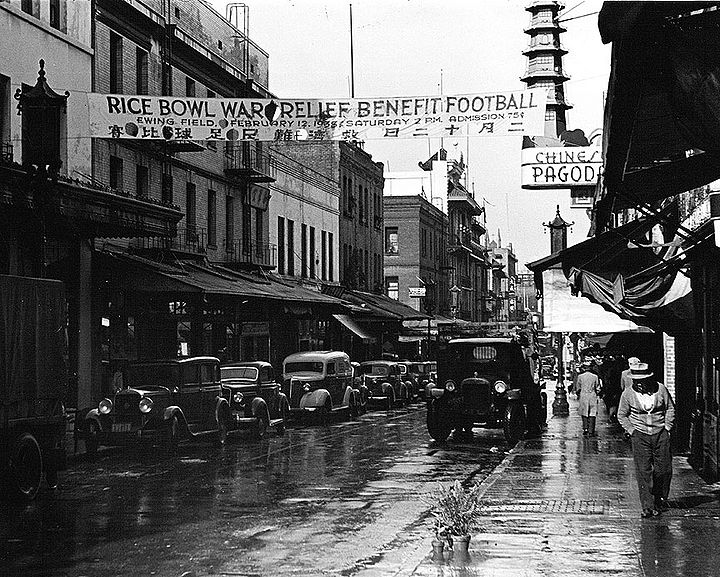

Chinatown street with banner advertising a February 12, 1938 benefit at Ewing Field.

Photo: Courtesy of Jimmie Shein

| For much of the time that the Chinese have been in America, they have faced discrimination and animosity. However, World War II changed much of that. When Japan became the U.S.’s enemy after Pearl Harbor, the Chinese in America found themselves in a position of opportunity to expand their economic and social influence. They distinguished themselves from the Japanese as much as possible, accepting and sometimes contributing to the racialization of the Japanese. After Japanese internment, Chinese merchants took over formerly Japanese-owned businesses. Furthermore, white perceptions of Chinese Americans changed due to the alliance between the U.S. and China, leading to the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Acts in 1943. |

Chinese Americans in San Francisco before World War II

The first U.S. immigration law that barred a group of people based on race was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The effect of this legislation, combined with the bachelor-heavy demographics of Chinese immigrants (a result of the Gold Rush era), was to stunt the growth of an adult second generation. But by the mid-1930s, there was a sizable amount of American-born Chinese, second generation Chinese Americans who were at once loyal to and identified with their Chinese heritage but also desired to be accepted into American culture (Wong 11). These foreign-looking Americans experienced severely limited economic opportunities because of widespread discrimination in jobs; they were frequently unable to find meaningful employment outside of Chinatown even when they were obviously qualified. Some decided not to pursue higher education because they saw no point of a degree if they could not even get a decent job (Wong 21).

Although these were American-born citizens, Chinese Americans still felt a great degree of allegiance to their homeland. In the 1930s, the Chinese reaction in America to Japanese expansionism and the onset of the Sino-Japanese War reflected the persistence and strength of their loyalties (Hong). They felt attacked, both abroad and at home:

“The war in China was a constant concern on the international front, especially for those who had families in China; the bleak economic and social prospects on the domestic front for the second generation were a persistent worry; and even within Chinatowns themselves, a safe haven was being threatened by competition from Japanese Americans…”(Wong 34-35)

Chinese Americans came up with several ways of supporting their home country. For example, they organized so-called Rice Bowl parties and parades to raise funds to send back home; these public demonstrations had floats, dragon dances, banners, and bands, and were surprisingly effective – San Francisco’s Chinatown raised $93,000 from a four-day Rice Bowl party (Wong 38). Another way Chinese Americans contributed to their homeland war effort was by boycotting Japanese goods, particularly silk (Wong 40), reducing Japan’s exports of silk by three-fifths from 1936 to 1938 (Wong 40). They also protested at docks where ships bound for Japan were moored, often recruiting sympathetic volunteers of other races (Wong 40). Individuals of different Chinese backgrounds began to work together to petition and pressure the government to intervene in China (Wong 35). San Francisco Chinatown was where much of the organizing took place, as a generation of Chinese Americans began to change society’s perceptions of them.

All these activities diminished the social isolation of Chinese Americans by bringing them into the public sphere and into close contact with mainstream America; with this increased visibility in the period leading up to U.S. involvement in the war, negative images of China and the Chinese began to change (Wong 43).

The War Effort

When the United States officially entered the war after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Chinese Americans were eager to contribute to the war effort, seeing their involvement as an opportunity to demonstrate both American patriotism and Chinese nationalism.

In general, the war allowed previously excluded minorities to fill jobs left by white men. Chinese Americans began working side-by-side with people of other ethnicities in the war industry, in shipyards and aircraft factories, as well as in white-collar professions (Wong 46). Chinese-American women were also leaving the domestic sphere and entering the workforce, many in defense-related industries (Wong 47). Although they were sometimes still segregated in their new jobs (Wong 52), Chinese Americans could, for the first time, find employment outside of the laundries and grocery stores and gift shops of Chinatown. For example, because the defense industry was a big employer in the Bay Area, 15 percent of all shipyard workers were Chinese in 1943 (“Momentous Change for Chinese Americans”). Chinese-American men also desired to enlist; 20% of the adult Chinese male population of the United States served (Wong 58). The military were actively seeking all Americans from all backgrounds, and the Chinese were wanted in a job for the first time.

Kenneth Bechtel, president of Marinship, a shipbuilding company located in Sausalito, wrote in a letter to Chiang Kai-shek:

“We have learned that these Chinese Americans are among the finest workmen. They are skillful, reliable – and inspired with a double allegiance. They know that every blow they strike in building these ships is a blow of freedom for the land of their fathers as well as for the land of their homes” (Wong 53).

Chinese Americans embraced the war effort, and their contributions helped usher in a new era of increased acceptance and social stature (Wong 72). Kenneth E. Kay, part of the Third Fighter Group of the Chinese-American Composite Wing, wrote: “Individually every Chinese man and officer was a human being in his own mold, a complex personality with his own idiosyncrasies, strengths, weaknesses, and talents….They were just like Americans, or Englishmen or Frenchmen” (Wong 65).

The “Good Asians”: Public Perceptions of ChineseAmericans

In fighting the Japanese, the United States and China became allies in World War II, and seemingly overnight, public opinion changed and decades of racism and systematic oppression were conveniently forgotten.

Wartime propaganda often attempted to distinguish the Chinese from the Japanese, displaying arbitrary, conflicting, and ignorant assumptions. The December 1941 issue of Life magazine had a feature titled, “How to Tell Japs(sic) from the Chinese,” where they characterized the Chinese as having a “parchment yellow complexion” as opposed to the Japanese’s “earthy yellow complexion” (81). According to them, the Chinese were tall and slender, while the Japanese were short and squat (82).

Although these descriptions are couched in flattering terms, the underlying racism was still present. A Pocket Guide to China, issued by the army, also portrayed the Chinese in a positive light, accompanied with a statement that American soldiers should not display racial superiority to the Chinese, not because of immorality, but because it might hurt the war effort by turning the Chinese against the U.S. (Wong 77-78).

Motivated by fear and indignation, Chinese Americans also tried to distinguish themselves as much as possible from the Japanese and “prove their undivided loyalty to the American war effort” (Hong). Mere days after Pearl Harbor, the Chinese consulate in San Francisco started issuing identification cards, and Chinese Americans began wearing buttons and badges with phrases like “I am Chinese” on them (Hong). Hoping to prove their loyalty to the United States beyond any doubt, Chinese periodicals also adopted the inflammatory anti-Japanese rhetoric and racial epithets used by the mainstream press (Hong).

Although there was some sentiment of pan-Asian solidarity, it was definitely not the norm. Chinese Americans, fueled by anger at Japanese aggression in their home country, their American patriotism, and their desire to be seen as American patriots, were, consciously or not, complicit in the persecution of their Japanese neighbors.

In his book, Americans First: Chinese Americans and the Second World War, K. Scott Wong describes how Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s tour of the United States helped improve popular opinion of the Chinese and Chinese Americans. Mayling Soong was born in China to a powerful and wealthy family familiar with the West, and attended Wellesley College in Massachusetts; after marrying Chiang Kai-shek, she became more involved in Chinese social and political affairs. The couple was famous, respected, and admired: In 1938 Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Chiang Kai-shek were named Time’s “Man and Wife of the Year” (Wong 73). When Madame Chiang Kai-shek returned to the United States in 1942, the response from the American public was overwhelmingly positive (Wong 95); after surprising the House and Senate with her fluent English and an eloquent, moving speech, she was described far and wide in both languages as the modern ideal of the Chinese woman. In San Francisco Chinatown, she was warmly welcomed, and even non-Chinese stores posted admiring advertisements in an attempt to attract Chinese-American customers (Wong 107), demonstrating the improvement of the social status of the Chinese. Because of her reputed intellect, charm, and beauty, public sentiment towards the Chinese improved via association.

While Madame Chiang Kai-shek was in the U.S., she spoke to several congressmen about repealing the Exclusion Acts (Wong 110), and arguably, because of her reputation and status, it was given serious consideration. In 1943, the repeal ended sixty-one years of exclusion, established a quota of 105 people based on the Immigration Act of 1924, and most importantly, it allowed the Chinese to apply for naturalization (Wong 121-122). It now must be noted that although this should be considered a victory, both sides of the repeal debate did not consider matters of morality or justice or equality, but rather framed the discussion in terms of the war effort, wartime goals, and America’s reputation.

Japanese internment and its effect on the Chinese-American population

The internment of the Japanese was more or less ignored by the Chinese community, with the exception of a few individuals (Hong). In fact, Chinese periodicals also participated in spreading the belief that Japanese Americans were guilty of treason or aiding Japan (Wong 84).

Japanese internment actually presented an opportunity for economic and social advancement to the Chinese. Chinese merchants moved into formerly Japanese-owned businesses on Grant Avenue (Hong). And when the Japanese were removed from their farm jobs, the United States Employment Service issued a call for Chinese Americans to replace them (Wong 83).

World War II was an opportunity for the Chinese to gain economic and social standing in mainstream American society; however, the shift in white America’s perceptions of the Chinese Americans must also be remembered as a consequence of racist attitudes directed towards the Japanese Americans and the ensuing internment of a whole ethnicity. Tides quickly shifted after World War II, when the United States declared another war, this time on communism. Power, given rather suddenly to the Chinese during the war, was just as quickly taken away afterwards.

Sources

Brooks, Charlotte. Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Hong, Jane. "Asian American response to incarceration." Densho Encyclopedia. 23 May 2014, 22:42 PDT. Web. 21 May 2015.

"How to Tell Japs from the Chinese." Life. 22 Dec. 1941: 81-82. Google Books. Web. 22 May 2015.

Wong, K. Scott. Americans First: Chinese Americans and the Second World War. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 2005. ProQuestebrary. Web. 20 May 2015.

"World War II Homefront Era: 1940s: Momentous Change for Chinese Americans." Picture This: California Perspectives on American History. Oakland Museum of California, n.d. Web. 22 May 2015.