CLASS CONFLICT IN S.F.

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

Labor Day 1936: Workers fill Market Street, reflecting their new power.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

| Throughout the history of San Francisco, successful worker organizing has corresponded to economic expansion and a limited labor pool. Responding to capital's boom and bust cycles, and the development of new technologies, unions were either strong or weak in their ability to advocate for workers, and emerged as a major force in pre-WWII San Francisco. Restructured and mobile capital through globalization began to undercut local labor, and pre-trade unionist organizing is becoming part of the new class struggle. |

Everywhere in the world, the schemes and dreams of ordinary working men and women have been caught in an elaborate dance with Capital's drive for profit and expansion. The particulars of San Francisco's class struggle during its century and a half of development are in many ways a quintessential example of the larger dynamics rapidly reshaping the world.

Time and again San Francisco workers organized and gained shorter hours, more pay, greater safety, more control, and all the things anyone would seek from any job. Typically such waves of organizing and victory corresponded to economic expansion and relative shortages of skilled labor. Right after the Civil War, thousands of San Francisco workers informed their employers that the 8-hour workday would replace the 10- or 12-hour days that until then were the norm, at the same pay. By 1867, several thousand workers marched up Market Street to Union Square to celebrate their success.

The employers of the city formed a "10-Hour Association" in 1867 to break this movement, and advertised for labor in eastern papers. The 1869 technological coup represented by the Transcontinental Railroad radically altered the labor market in San Francisco. Thousands of unemployed men came to the city, unions were broken, wages slashed, and hours extended.

The interplay between organized labor and capital led to a series of efforts on both sides to combine forces and fight more strategically. Depending largely on the boom-and-bust cycle, workers would gain higher wages and shorter hours when business was good, and employers would succeed at imposing the open shop and wage cuts when times got tougher. Workers created many hundreds of different unions, and these locals joined larger councils or national unions or both. Many of them lasted only a few years or decades. Employers in their turn have formed extralegal and illegal associations repeatedly to carry on their side of the class war in San Francisco, usually counting on the SFPD as reliable backup or front line troops (1900, 1907, 1916, 1921, 1926, 1934).

This dynamic climaxed in the 1934 General Strike, in which the workers lost the battle but put a lethal dagger into the heart of fifteen years of "American Plan" propaganda and open shop conditions.

After enduring hundreds of short wildcat strikes during the '30s, employers naturally began to look at the bigger picture. How could the chokehold of organized labor be bypassed, if not defeated? How to eliminate those pesky neighborhoods full of memories, full of class consciousness, short of mass murder or war?

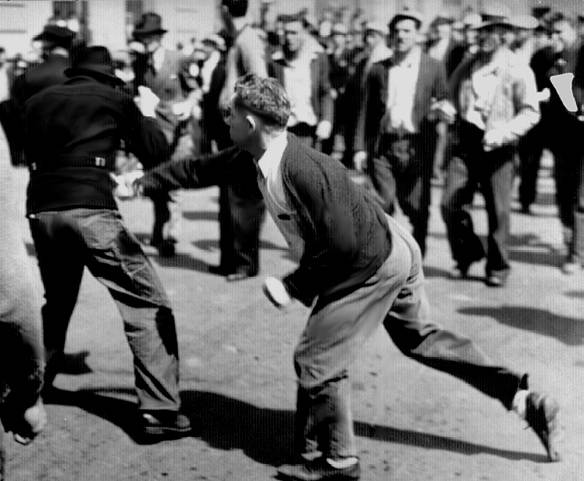

Striking longshoremen in 1938 attack scabs along the waterfront

1938 Strike: scab being attacked.

Photos: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco, CA

Ruling class planning in San Francisco faced an entrenched, self-confident, smart, historically savvy working class in pre-WWII San Francisco. The massive expansion of industrial production for the war began a process which local planners endorsed and extended in the post-war era. Ultimately they succeeded in regionalizing the Bay Area economy, moving shipping to Oakland, heavy industry to the north and east bay, spawning hi-tech industries around university enclaves, and so on. And that regionalization process undercut the strength of unionized workers as the accompanying modernization and mechanization helped restructure entire industries.

Butchers march on Market Street during Labor Day march, 1934.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

As the blue collar employment base of the city was systematically moved out, so too were the neighborhoods most connected to the living legacy of the Big Strike "the South of Market (home to thousands of retired longshoremen) and the Fillmore (the African-American cultural center during the 40s and '50s). Economic planning led to globalization, assigning San Francisco to be a Headquarters Hive, home offices wired together, overseeing a far-flung network of production and distribution. The San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, the municipal planning and building agency answerable only to itself (SFRDA), pursued a slum clearance approach to two venerable, lively and neighborly areas. The home of retired longshoremen (SOMA) and the great wave of southern blacks that came to build ships in WWII (the Fillmore), the reservoirs of local working class knowledge and history, were systematically razed, the inhabitants largely dispersed.

The longshoremen under Harry Bridges stood at the radical edge of unionism in 1934, but after two decades, Bridges and his colleagues began to discuss the terms of capitalist modernization. By 1960 they signed the Mechanization & Modernization Agreement, which gave the union a lot of money, the workers good pensions and guaranteed hours, and the owners were allowed to begin containerization. The contract was renewed in 1965, the job security clause being dropped since the Vietnam War was keeping everyone on overtime anyway. By 1971, the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union (ILWU) voted 94% to strike against accepting "steady men," the owner's demand to directly employ the longshoremen operating their $2 million cranes. When they lost this strike after 106 days, the Port of San Francisco was doomed to a non-shipping future.

This underlying pattern can be seen throughout the global economy. As workers become more solid and organized, capital either mechanizes and restructures, or moves (or both). Urban redevelopment can be placed firmly within the logic of class war, since the areas designed as "blighted" correspond to zones of heightened awareness, political skill and active resistance.

As social movements evolved through the upheavals of the 1960s and against the background of the permanent ("cold") war, organized labor became an aggressive agent of the capitalist order. Unions supported anything that seemed to "create jobs," leading the charge for San Francisco's absurd and finally truncated freeway plan, as well as uncritically supporting Manhattanization and "redevelopment" of its own residential neighborhoods. Ultimately this short-sighted economism led to the rapid decline of trade unionism as a political and economic force. The transmission belts of working class culture and memory were broken and the occasional attempts by workers to resist were forced out of the union structure (see "No Paid Officials"). Decades passed before labor activists began to see how post-WWII mid-century prosperity was not permanent, and that resistance would have to face the global reach of the modern economy. But union power is so weak now that a new strategy of working class resistance is required, one that in turn outflanks capitalism's globalism with goals and tactics completely outside the logic of capitalism's occasionally stubborn partner, trade unionism.

In 1980 the Office Professional Employee International Union, Local 3, sent 1,100 Blue Shield data processing workers out on strike that ultimately lost badly with only 150 returning to work. The infamous Air Traffic PATCO strike in which President Reagan fired them all was not long after. The Greyhound Strike in 1991 was a dismal defeat. The two-month newspaper strike in late 1994 ended in something of a draw, but ultimately is a win for management's efforts to reduce employment. San Francisco trade unions were buoyed by the convincing victory of the Mark Hopkins workers in their 1994 strike. Local 2 of the Hotel and Culinary Workers Union continues to maintain union shops in most of the large hotels and restaurants in town. But the gourmet ghettoes and restaurant rows in the neighborhoods remain alien territory as far as Local 2 is concerned. SEIU is the largest union in San Francisco in 1995. It represents city workers in dozens of jobs as well as some private sector janitors, hospital workers, and other white collar workers.

Exploratory attempts to organize bank workers were made by a group calling itself "Bankworkers United" in the early 1980s, but by 1986 they had vanished in the shake-up that preceded Crocker Bank's merger with Wells Fargo Bank. A different approach was pursued by a group of radicals around Processed World magazine. Union campaigns have succeeded mostly in hospitals and universities. San Francisco is no longer a union town, though some lip service is still paid to the idea occasionally.

Curiously, a return to the pre-trade unionist radicalism of the post-Civil War era may be more promising than any attempt to achieve a balanced "bargaining power" with international business. In the political effort to reclaim and redefine "place," defend local ecology and economies, the old class struggle is taking its new shape. When we begin to fight for work worth doing and local cultural diversity, against multinational creeping monoculture, we escape the narrow logic of capitulation and austerity which logically proceeds from the way things are in the global capitalist order.