Battle for Bodega Bay: The Sierra Club and Nuclear Power, 1958-1964

Historical Essay

by Thomas Wellock

Originally published in California History magazine, Summer 1992, Volume LXXI, No. 2. Posted here with permission.

Bodega Head, looking east across Doran Park, ca. 1960. The nuclear plant, to have been built in the lower right area of the photograph, would have necessitated stringing utility lines across the harbor entrance and through the park.

Photo: Courtesy David Pesonen

In the spring of 1958, Dr. Edgar Wayburn, chairman of the Sierra Club's conservation committee, received a confidential letter. The sender wished to remain anonymous because he did not "know how far the long arm of PG&E [Pacific Gas and Electric Co.] reaches in this matter." The nation's largest utility had approached Rose Gaffney, the owner of a large tract of land on California's Bodega Head peninsula, to inquire into the purchase of her property for an electric generating facility.(1) This news disturbed Wayburn.

Fifty miles north of San Francisco, Bodega is an isolated area of scenic charm that the State Division of Beaches and Parks had planned to acquire. The PG&E representatives told Gaffney that the parks division had withdrawn its interest. Although Gaffney responded that she had no desire to sell to PG&E, the aging woman actually had little choice. States had long ago delegated their power of eminent domain to electric utilities, since power plants were considered to be in the public interest. On May 23, N. R. Sutherland, the utility's president, announced that land acquisition was underway.

PG&E was about to embark on the construction of the nation's first commercially-viable nuclear power plant. Their efforts, however, became mired in concerns for the environment, questions of safety, and accusations of a conspiracy to subvert democratic institutions. PG&E emerged from the first significant citizens' battle over nuclear power with its reputation scarred and a new respect for the power of the conservation movement that was coming of age politically in the 1960s. The controversy illuminates the growing dissatisfaction with the power relationships inherent in the existing political order and the identity crisis the environmental movement faced when confronted with social and internal expansion.

The issue emerged at a pivotal time in the Sierra Club's history. The protests in the early 1960s against the Bodega Head plant led directly to the notorious Diablo Canyon negotiations with PG&E that split the club and forced Executive Director David Brower's resignation in the late 1960s. Even before the Diablo Canyon controversy, Bodega clarified the issues of nuclear power and wiped away any ambivalence some club members felt about opposing nuclear energy. At the same time, other club members persisted in the post-World War II faith in nuclear energy as a relatively benign alternative to using fossil fuels and building more hydroelectric dams in wilderness areas. The earlier controversy thus established the terms of debate that, in the subsequent project at Diablo, proved impossible for the club to solve. Bodega marked the beginning of a transition in the traditional conservationist agenda of preserving a remnant of scenic lands for public use favored by older Sierra Club members, to a new generation's concern for the influence of economic growth and technology on the environment generally. The old guard believed their position best preserved the club's non-partisan, tax-exempt status and cooperative relations with government and industry. In abandoning this position, the Bodega Head insurgents created an ad hoc organization that was committed to political activism. It foreshadowed a similar direction by Friends of the Earth in the dispute over Diablo Canyon. In the long run, the Sierra Club also joined in that activism.

These changes within the environmental movement were rooted in the United States' economic and population growth after World War II. While the liberal state relied on growth to solve economic and social problems, the conservationist movement viewed nature in Malthusian terms: the wilderness was a zero-sum resource and expansion could only come at its expense. Environmentalists, in general, relied on the state to finance their agenda, trusted its experts, and were committed to institutional reform. At the same time, they were threatened by the expanding capitalist economy and found themselves pitted against expert opinion and an intractable political system. Bodega is palpable evidence of this inherent conflict.

Nuclear power was particularly susceptible to attack because the technology appeared to be more "elitist" than most. In the 1950s, conservatives in the Sierra Club and the public accepted the argument that nuclear power was best left to the new priesthood of engineers and physicists within the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). Club members at first supported the AEC's emphasis on expertise and "impartiality." The club hierarchy included physicians, professors, and attorneys who disdained the politics of the street and citizen activism. Traditional club leaders, such as lawyer Richard Leonard, embraced the view "that we can accomplish more by dealing with intelligent people at the top [of government or industry], who then give orders and gradually make changes in the philosophy of the people under them."(2)

But such a philosophy was anathema to the rising radical sentiment of the New Left and other protest movements of the 1960s. They maintained that all issues carried political implications and elitism only served the entrenched political order. Contemptuous of the "abject worship of technology," radicals saw the movement's strength in confrontation and citizen activism.(3) The Bodega experience indicates that New-Left ideology influenced the antinuclear movement earlier than the late 1960s as is usually acknowledged.(4) The salient issue of earthquake hazards surrounding Bodega, which was used to attack the nuclear plant, has led researchers to overlook the broader political aspirations of the antinuclear forces.(5) Activists employed safety questions in public debate, but a desire for participatory democracy and decentralized decision-making also motivated them. This is not to say that activists openly identified with the left, but the radical critique of centralized authority did hold a powerful appeal. What can thus be said of the power plant opposition was that it managed to be everything to all people. Its broad appeal touched those concerned with aesthetics, safety, and the more militant environmental and political philosophy of the 1960s.

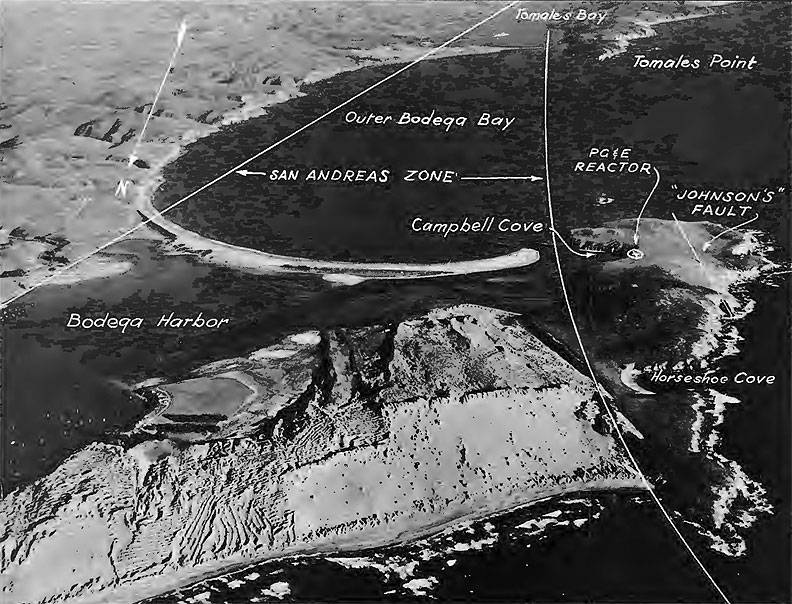

Aerial view of Bodega Bay and Harbor, looking south. One thing to note here is that the photograph provides evidence that Bodega Head, to the right of Johnson's Fault, is moving northward. Not unprecedented, the head moved twelve feet during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

Photo: Courtesy David Pesonen

After being alerted to PG&E's plans for Bodega Bay, Edgar Wayburn spent the Labor Day weekend in 1958 camping near the head. He met with Gaffney and viewed the Indian artifacts she had collected from the area. He strolled among the ecological communities interspersed among its high granite cliffs and sand dunes. The peninsula contained a vast array of flora and fauna in its grasslands, intertidal pools, harbor mudflats, and marshes. While these ecosystems of Bodega Head may have been of interest to University of California scientists who hoped to use Bodega as a marine research center, it was its picturesque beauty that concerned the Sierra Club. This, too, Bodega possessed in abundance. Convinced that Bodega Head's splendor needed to be saved, Wayburn attended the first meeting of the new Redwood Chapter of the Sierra Club and encouraged them to spearhead the opposition to construction of any power plant.(6) The club passed a resolution at the summer 1958board of directors meeting in Yosemite National Park directing that "action be taken for [Bodega's] immediate acquisition" by the state.(7)

The club's quick moves gave the appearance that it would fight for Bodega as it had on issues of aesthetics and wilderness preservation in the past decades. Dr. Joel Hedgpeth, director of the Marine Biology Station at the University of the Pacific, was confident that "Sierra Club attorneys are now standing by" to help Gaffney.(8) However, board members were not willing to approve any substantive action beyond simply criticizing PG&E's plans because they threatened a scenic area. Despite Wayburn's directions, the Redwood Chapter offered little opposition. "They were new people," he recalled, "and some of them were influenced locally by PG&E . . . . PG&E would find out the Club leadership would be opposed to something and go to local club members to get their support."(9)

But even this moderate activism was a break from the club's sleepy past. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s the group drew its membership from hikers and mountain climbers, most of whom were uninterested in political activity.(10) In response to increased logging of wilderness and dam projects in the Southwest, the club abandoned this limited role in 1953, when the board of directors approved the formation of chapters outside California and agreed to take on more vigorous campaigns to protect scenic areas from encroachment. The club's opposition to Bodega, based as it was on aesthetics and wilderness preservationism, reflected this new philosophy. This position avoided the appearance of political bias and would not risk the club's tax-exempt status. Citizens opposing the Bodega plant for more politically adventurous reasons would have to find active support elsewhere.

Yet it was PG&E who found allies in local business groups and politicians. Hostile to environmental concerns, the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors held to the traditional conviction that scenic areas looked best when developed. Supervisor E.J. "Nin" Guidotti remarked that "it just didn't make sense ... to have 'a beautiful area' [like Bodega] and 'just leave it undeveloped forever." With a power plant Bodega would "be developed a lot faster than if the PG&E plant were not located there."(11) County Administrator Neal Smith thought the plant's power lines through Doran Park would look "artistic."He derided opposition to the plan as "just a lack of understanding."(12)

To cultivate their support, PG&E treated the supervisors to junkets at plants near Morro Bay and Hunter's Point. Officials declared that "a public hearing was not... necessary."(13) In November 1958 the board ignored 1,300 petitions from angry residents and approved a use permit for the Bodega plant by a vote of four to one.(14)

PG&E refused to disclose whether the plant would be coal or nuclear, but it was clear that the utility favored nuclear. The company announced in the spring of 1959 that "an atomic plant will be built in one of the nine Bay area counties. .. as soon as it can be done at a reasonable cost."(15)

Further indication of their plans to go nuclear came when the utility moved the site of the plant on the head a sufficient distance away from the San Andreas fault to comply with Atomic Energy commission regulations. Joel Hedgpeth considered PG&E's claim of indecision on the plant to be a "fantasy."(16) As Hedgpeth would learn, the federal government was of no help either. The AEC was more interested in accelerating atomic construction than investigating earthquake hazards.(17)

Bodega Bay citizens groped for some effective vehicle to fight PG&E. The majority of the villagers took a dim view of construction of the power plant, and cared little for the tax benefits it offered. They agreed with the Sierra Club that the plant and its power lines would be a wart on the landscape. Fishermen feared that the plant's location and thermal discharge would interfere with their livelihood. Others, as activist Hazel Mitchell remembered, did not want their simple, isolated lifestyle disturbed. Residents recognized that some organized body was necessary to speak for the fragmented citizens and represent local interests. In 1959 Mitchell and others created the Bodega Bay Chamber of Commerce to exhort area residents to become more politically active and write their representatives. It was a logical, if pitifully small, step toward organized opposition. The chamber members would often resort to scouring the local restaurants to constitute a quorum at their meetings.(18) Local citizens thus spent these lonely years without significant support from the Sierra Club, the community, or the sympathetic ear of a government body.(19)

The situation within the Sierra Club was far from static, however. The club's singular reliance on aesthetic arguments came under mounting criticism from its members. By the end of the 1950s, a sense of urgency drove some club members; their generation, they had come to believe, would be the last to have any chance of saving the wilderness for their children. Wayburn could envision the day when the wilderness would be lost forever "unless we change our way of doing things."(20) The discredited theories of the nineteenth-century economist Thomas Malthus were taken off the shelf and put back to work. Neo-Malthusian tracts appeared in the late 1940s and early 1950s.(21) Their authors' message for humanity to restrict its demands on nature was particularly attractive in California, where a burgeoning population generated pollution and threatened wilderness resources. The Sierra Club found itself fighting new freeways through state parks and construction on the Pacific Coast. Utility executives looked hungrily to these same shores to satisfy the state's appetite for electricity.

At the time, even to friends of wilderness preservation, nuclear power seemed to be an answer, not a problem. The hazards of nuclear power were little understood by the public, and it was considered a "clean" alternative to fossil fuels. Environmentalists particularly embraced the new technology as a way of saving the wilderness from large dam projects. In the club's successful fight to save the Dinosaur National Monument from a dam at Echo Park, David Brower, the club's executive director, claimed that wilderness-preserving alternatives such as nuclear power could serve as a substitute. Brower's conduct during the campaign exemplified the ideal of reasoned negotiation, but board member Richard Leonard's accommodationist philosophy nettled him. Brower thought it necessary "to fight off a threat whenever it first appears."(22) He did not accept an impartial role for the club. Boldness, "not objectivity," served environmental purposes.(23)

He sat in his office and plotted growth rates that were nothing short of frightening; the year 2005 would find 90 million Californians scrambling for space near his beloved Sierras.(24) In the face of such a threat, conservation aims were better served by militant action. Brower, a World War II veteran, often employed military metaphors to describe conservation campaigns. The club's seventeen thousand members, he noted in his diary, were "about like [the size of] a division" and ready for action. "Maneuvers are over." (25)

In the late 1950s, Brower and Edgar Wayburn occupied a centrist position in the club's ideological spectrum. Despite his belligerent rhetoric, Brower was not averse to compromise as long as all the facts of the deal were known. More militant than Brower were members of the staff that he personally recruited. To administer the club's day-to-day operations, Brower drew on young, idealistic conservationists from institutions such as the University of California at Berkeley. Many, such as Conservation Editor David Pesonen, who was drawn into the Bodega fight, held an open contempt for the old guard's elitism and institutional emphasis. It was through this link that the influence of Berkeley's radical community, with its focus on civil rights and liberties, spilled over onto the conservation movement.

Placing individuals in static categories, however, oversimplifies the difficult struggle Sierra Club members faced trying to resolve the questions raised by America's enthusiasm for expansion. How could club members object to the liberal consensus on growth when social reform and the financing of conservation measures depended on it? Conservationists loathed accusations that they opposed progress or technology, but Brower thought the issue had to be faced. At the club's fifth Wilderness Conference in 1957, he acknowledged that critics would label conservationists "neo-Malthusian," but he declared that theirs was not "blind opposition to progress, but of opposition to blind progress." The executive director warned that the issue had to be faced quickly, since "the wilderness we have now is all that we and all men will ever have."(26)

Brower's two statements proved irreconcilable. Some would choose the former and accommodate growth through planning; those in the latter camp drew a line and stood absolutely for nature. The fact that both thoughts existed within the mind of the same man demonstrates the ambivalence conservationists felt. But Brower's ideological division with conservatives was evident when Richard Leonard disagreed with his mountain-climbing partner and expressed his own optimism that the best minds in the country could apply "corrective action."(27)

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Brower was fighting infringement of scenic areas in tones that grew more strident every year. He disdainfully referred to the "cringe benefits" of IRS exemption that rendered the club's "hands bound . . . and our voice muffled."(28) Uncomfortable with the risk his attacks posed to the club's tax status, the board of directors passed what Brower dubbed the "Gag Rule."The 1959 resolution proscribed club officials from making any statement that impugned the motives or integrity of public officials.(29) The board used the new restrictions to rein in Brower in disputes with the Forest Service on "multiple-use" forest management. The executive director's bitterness at the board's actions spilled out on the pages of his diary as the 1960s began: "Currently the answer to growing pains seems to be to assemble all [the] living [club presidents] possible and vote new restrictions on the staff, and to take public action that will humiliate [them]-as [a] reward for [the] development of [the nation's] leading conservation organization."(30) The patience he displayed in the 1950s would wear thin as disputes grew bitter in the turbulent decade that followed. Disagreements over the urgency of wilderness preservation would be played out in schisms over proper tactics.

Discontent in the lower echelons of the club seeped out despite the board's restrictive measures. In December 1960, Phillip Flint, a member of the club's Conservation Committee, sent a letter to Berkeley's chancellor, Glenn Seaborg, and Governor Edmund Brown to request their assistance on the Bodega power plant question. Flint claimed PG&E "bypassed much of the public debate which should accomplish the solution to such a problem."(31) The board of directors was scandalized that the letter escaped club review. It was not that the directors trusted PG&E, in fact, board member Lewis Clark concluded the letter expressed a number of beliefs . . . that are shared . . . by a majority of the officers of the Club." But "through faulty internal communication we have succeeded in antagonizing both the PG&E and the county Supervisors, thus jeopardizing the possibilities of persuasion."(32)

Unfortunately, an institutional solution seemed remote. Edgar Wayburn appealed to the state Public Utilities Commission (PUC) president, Everett McKeage, to consider aesthetics under the commission's broad regulatory powers. The club's hopes were dashed by McKeage's reply that "the matter of the particular location . . . is, usually, left to the discretion of the [utility] management unless a clear abuse thereof is shown."(33) The PUC's refusal to consider aesthetics and its rationale for doing so meant that no public agency was responsible for the protection of scenic areas; all decisions were left to a private corporation.

In the summer of 1961, PG&E removed any remaining doubt regarding what type of plant Bodega would be. In simultaneous announcements the Atomic Energy Commission declared that nuclear fuel costs would be cut 34 percent, and PG&E revealed that Bodega would be a 325 megawatt Boiling Water Reactor. Bodega was to be a ground-breaking facility. It would be the first economically-competitive commercial reactor in the industry.(34) The peaceful atom had reached maturity.

The dawn of civilian nuclear power had been long in coming. Its difficulties in the 1940s and early 1950s stemmed from Cold-War fears and secretiveness. By the early 1950s, the members of Congress were eager to see commercial power developed, but the two major parties differed on who should benefit from the atom. The 1954 Atomic Energy Act tended to favor private industry, but public-power Democrats bitterly fought private development throughout the 1950s. By the late 1950s, the only significant opposition came when congressmen induced the United Auto Workers to oppose the abortive Enrico Fermi breeder reactor plant near Detroit. The public issue hinged on the safety of the untested design. Public power Democrats and labor unions opposed the plant because it had been built by a consortium of private utilities, and 1956 was a presidential election year.(35) After Fermi and public-power battles—such as the Dixon Yates controversy, public opinion in the conservative 1950s turned decidedly against the "creeping socialism" of public power.(36) The wounds sustained by public-power advocates, who were accused of being Communists, festered for years, and they waited for the right opportunity to resume the fight.

For the moment, the way seemed clear for approval of the Bodega plant. The PUC hearings held in San Francisco in early 1962 attracted little interest and were sparsely attended. Even the Sierra Club was absent. Joel Hedgpeth, who had placed his faith in the club, denounced its failure to act. In a letter to the PUC he charged that the club had "betrayed the memory of its patron saint, John Muir, who fought Hetch Hetchy on his deathbed."(37)

Alfred Hitchcock's filming of The Birds in Bodega Bay was as much of interest in local circles as was the nuclear power issue. That both events illustrated the theme of man's relationship to nature seems to have gone unnoticed. Help came from other quarters, however. Karl Kortum, director of the San Francisco Maritime Museum, used his friendship with the Chronicle's editor, Scott Newhall, to have a letter on the Bodega plant prominently displayed on the editorial page.(38)

Kortum accused PG&E of subverting the democratic process and of being callous "demigods." He appealed for concerned citizens to "take five minutes to write a letter" to the PUC.(39) The public response was so overwhelming that the PUC rescheduled additional hearings for May 1962. Rose Gaffney, whose property had been seized by PG&E, enlivened the new proceedings with a colorful slide show of Bodega Head, and frequent outbursts from her seat in the audience aimed at public officials.(40) The Sierra Club also responded to Kortum and this time sent representatives to the hearings. Significantly, the club dispatched two young staff members, Conservation Editor David Pesonen and lawyer Phillip Berry. In testimony, Phillip Flint accused the utility of "collusion" with county officials in secret meetings and with similar involvement with the Parks Division and the University of California.(41) Pesonen supported Flint and claimed Bodega was a "sacrifice" for "an experimental feather in the company's economic hat."(42) Berry followed up by arguing that the University of California appeared to be an accomplice, by their "complete reversal in position" in 1960, when they abandoned plans for a marine research station at Bodega that cleared the way for the plant.(43) He asked that university faculty and officials be subpoenaed to, as he later put it, "tell the whole truth of [the university's] failure to oppose PG&E's application."(44)

The conduct of their militant representatives, who had impugned the motives of so many government officials, incensed the club's executive committee. Pesonen was undaunted. Convinced that the club's stand on scenic values could not defeat PG&E, he suggested that the club use the issue of safety to cast doubt on the plant. As Leonard led the attack on this proposal in an executive meeting, Brower remained silent. His subordinate's willingness to challenge the AEC was a step farther than the executive director was yet ready to go. Neither the board nor Brower could countenance a proposal that would directly question government and industry experts. Leonard considered Pesonen to be an "extremist."(45) But years later Brower rejected the radical label for Pesonen:

He may have frightened [the directors] a bit. I think they realized, as PG&E later realized, that they were up against a tough customer . . . . I think that simply he was right and I wavered. That was a time when I could have been tougher; I could have said, "If Pesonen goes, you're going to lose another David too."(46)

Although Pesonen quit the staff to lead the fight against the plant, his departure did not settle the dispute within the club. Brower remained concerned that the directors did not recognize the club's "tremendous influence and power .... We are national in the influence we can bring to bear, and we are looked to for what we are not producing."(47)

Club attorney Phillip Berry hammered out a letter to board member Leonard attacking the other lawyer for "an obsession with the idea of maintaining the Club's favorable tax status" that risked its historic mission.(48) To Leonard, Berry's accusations at the Bodega plant hearings raised serious questions of legal ethics. He read the1959 resolution to Berry verbatim and averred that "the 'goal of winning'. .. does not permit one to disregard the 'means'."(49)

The club's directors passed a resolution that reiterated the old position that power plants were only a menace when located "along ocean and natural lake shorelines of high scenic value."(50) The dissenters lost this round; the club would not lead the fight against Bodega.

Young David Pesonen typified the new activists in the 1960s. Articulate, motivated, idealistic, and committed to environmentalism, he earned a degree in biological sciences from Berkeley in 1960. His father's strong advocacy of public power left the young Pesonen without any "particular awe" of PG&E.(51) A self-described "non-violent anarchist," he held to a philosophy that reflected the New Left ideology of decentralization, participatory democracy, and deep distrust of elites controlling technology.(52) He longed for social reform and despaired at the pace of change. Just two years before the 1964 Free Speech Movement at the university, he complained that "a really socially important idea would be an orphan [at Berkeley]."(53)

In conservation matters, Pesonen feared the speculative suburban development that threatened the proposed Point Reyes National Park and Bodega Head. He scoffed at government agencies that contended "it is not growth itself that is the problem, but the pattern of growth." "Growth is the problem,"he maintained. Pesonen feared that solutions could not be found in existing institutions and that the democratic process would be corrupted.(54)

He was distressed that Americans had been seduced into abdicating control of their lives and political power to a "small elite corps of nuclear experts" in an "abject worship of technology."(55) "Progress, the flower of the poppy," he warned, "has debauched [the political system] at Bodega Bay."(56)

In his battle against the nuclear plant, Pesonen became the executive secretary of the foundering Northern California Association to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor. Pesonen borrowed the extensive newspaper clipping file that Joel Hedgpeth maintained on Bodega and wrote a series of September 1962 articles for the Sebastopol Times. Pesonen outlined the sordid details of a local government system that followed PG&E's every wish to ensure that the plant was added to the tax base. "The company had undoubtedly obtained vague commitments from a few key individuals in the county and then pursued them, exploiting promises given." The conspiracy reached every level of government, according to Pesonen. The university and the Parks Division had been similarly influenced through "subtle perhaps political pressure" by the AEC, the governor, or PG&E.(57) The alternative Pesonen proposed to this conspiracy was decentralization and participatory democracy:

All the risks, which have been swept under the rug for four years, should be fully aired before the people who must in the last analysis, run them. Although the fact has been somewhat obscured in Sonoma County, local government is the backbone of Democracy.(58)

Pesonen's conspiracy theory was at least half correct. Supervisor "Nin" Guidotti admitted later that the supervisors had held secret meetings with PG&E as early as 1957 in violation of the Brown Act prohibiting such covert dealings. The board insisted that these meetings were nothing more than fact-finding missions and that no decision was made until 1960.(59) "We did not meet in alleys to fool anyone," Guidotti insisted. "Everything we did was open and above board."(60) Correspondence in the archives of the University of California at Berkeley, however, indicates that the supervisors had decided in favor of PG&E even before the utility's announced intention to acquire Bodega in 1958.(61)

PG&E construction site at the mouth of Bodega Harbor in the early 1960s. The earthquake fault that ultimately forced the cancellation of the project ran through the excavation area—the circular pit— shown in the foreground.

Photo: Courtesy David Pesonen. Photo reproduction courtesy Instructional Media Center, CSU, Hayward

Despite such appearances, Pesonen's accusation of complicity by the Parks Division and the University of California is probably unwarranted. The supervisors could stymie the park project or the university's research facility, since such plans needed county approval. The university had few alternatives but to enter into negotiations with PG&E to use some of their land. In 1960 Chancellor Seaborg scrapped the university's plans when it seemed likely that thermal pollution would damage its marine station's usefulness. PG&E quickly offered to alter the plant's design to minimize the danger. In the meantime, Seaborg consulted university counsel as to the possibility of a legal challenge. They advised him that the university would have to demonstrate a need that no other site could fill in order to force PG&E to move. Other less ideal sites did exist. Later that year, when professors requested the chancellor fight for Bodega, he already knew this avenue was unlikely to succeed.(62)

Nevertheless, Pesonen's 1962 article convinced many that a conspiracy existed and encouraged them to join the plant fight. From his position as Sierra Club executive director, the chastened David Brower did what he could to help Pesonen "under the table," by printing the articles as a pamphlet, "A Visit to an Atomic Park."(63) He suggested to the club's board that the pamphlet be a club publication. The directors balked at even this moderate level of aid and agreed only to "distribute" it. In a letter to the executive committee, Brower protested that the club was "indulging in massive hesitancy":

The only adequate coverage was by Dave [Pesonen], who stood his ground and fought for what the Sierra Club was founded to fight for. ... I have been on the firing line for ten years, sometimes moving forward above ground, but too often lately crouched in a foxhole because of vague fears not my own.(64)

Club members were genuinely confused as to the best policy toward nuclear power. Former president Harold Bradley donated money to the "young Galahad" Pesonen, but thought the club was contradicting itself by opposing nuclear power when it had been the club's "strong belief" earlier that the atom could replace hated dams. He mused to Brower that "you and I ... used this argument fervently—and believed it. Now here it is!" Bradley thought raising safety issues now could undermine future scenic battles. "I suspect we shall be fighting the Echo Park dam again one of these days. How strong will the argument sound if we oppose nuclear reactors today on grounds of danger?"(65) Brower could only respond that safety problems meant America should "give coal a good try first."(66) But Bradley recognized Brower was not addressing the real problem that Bodega manifested. "Preservation is doomed if population is not controlled!" he predicted.(67)

Pesonen felt none of Bradley's discomfort with ideological inconsistency or Richard Leonard's desire to be objective. When Hedgpeth gave testimony that was honest but damaging to their efforts, Pesonen chided:"If you had been as unscrupulous as [the opposition] just this once, it would have strengthened our position immeasurably."(68) The younger man brought coherence and single-minded devotion to the Northem California Association to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor. For help he turned to the Berkeley campus. Berkeley's faculty had a long history of environmental interest, and their growing alienation from the university administration made them a logical ally. As the Free Speech Movement and Bodega Head controversy attest, students and faculty were willing to use militant tactics and political insurgency.(69) In the fall of 1962, Pesonen, other Sierra Club members, and Berkeley graduate students and professors organized an educational meeting in Sonoma County. The meeting sponsored a number of speakers to discuss topics of safety and the political implications of PG&E's plans.

At the meeting, the sponsors put forth a gospel of no-growth and claimed that the Bodega plant would radically alter the character of the rural county. They warned the audience of 150 that "preparations for growth are a primary cause of growth." To maintain a community in which they would want to raise their children, the sponsors encouraged them to avoid participating in the politics of expansion and base their choices not on economics but social values.(70) Pesonen delivered his message decrying the "abdication of the citizens' responsibility into the hands of government experts."(71) The speakers exhorted the audience to organize "neighborhood meetings"and letter writing campaigns.(72) Pesonen's most potent weapon proved to be government spokesman Alexander Grendon. In countering the protestor's warning about the plant, Grendon informed the audience that they were wasting their time, since it was up to the industry and AEC to determine the appropriateness of a site. County resident Doris Sloan, who had been only marginally active in the fight thus far, was "outraged" by Grendon's arrogance, as was most of the audience. As she later recalled, it was the political issues that motivated her to assume leadership of the local campaign.(73) Pesonen had gained a valuable ally. Sloan had been active in beautification campaigns against billboards and knew how to organize at the local level. The people left that night with a hope and determination that infected the organizers; in the margin of Pesonen's speech was scribbled: "All is not lost."(74)

But the fight did seem lost. On the very day of the Sonoma County meeting, the state PUC gave its approval to PG&E subject to thermal pollution and radiation studies.(75) Pesonen's association responded to the crisis in late 1962 by devising a strategy that followed three paths—citizen protest, legal intervention, and impugning the integrity of public officials. Pesonen and other members filed four appeals to the PUC requesting a new hearing; all were denied. Members accused the university of attempting to silence the faculty and of hiding a correspondence file that would prove its complicity with PG&E. Following the advice of Hedgpeth, Doris Sloan and others charged the supervisors with "what appears to be a malfunctioning of the democratic process." They repeatedly petitioned the Sonoma board and were twice rejected and eventually restrained from discussing Bodega at supervisor meetings. All this activity made it clear to the public that government officials were stifling their constituents.(76)

The real goal of the Northern California Association to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor was to destroy the power base of officials who opposed them. Area citizens initiated a petition to recall "Nin"Guidotti for violating the Brown Act, a campaign Pesonen considered the "keystone" to their entire effort.(77) Guidotti was a good target since he had a talent for verbally abusing his rivals and making pithy, embarrassing statements that made headlines.(78) The opposition sponsored a "Nin" Day on which they held a parade in his horne town featuring his effigy drawn and quartered.(79)

Although the recall effort failed on a close ballot in the fall of 1963, the days when supervisors could ignore the public were at an end.

Doris Sloan, a Sonoma County resident, shown here in 1962, organized other activists in a prolonged political battle against county supervisors, who refused even to acknowledge a constituency opposed to their pro-Bodega position. Since its inception, the environmental movement has always included activists such as Doris Sloan (who later went on to a career in environmental science), Rose Gaffney, and Hazel Mitchell. Although women had taken a major role in the Sierra Club and other early conservation movements, it was in the decade of the 1960s that they particularly emerged as leading environmental activists, especially in organizing grass-roots campaigns.

Photo: Courtesy Joel W. Hedgpeth

The dissatisfaction with authority evident in the campaign against the Bodega plant underlines the fact that such resentment had a broad appeal for groups other than college-age students. While unrest had been stirring at Berkeley since 1957, Sonoma County's activism followed a parallel path. "It was people wanting participatory democracy," Sloan remembers, "wanting a say in decisions, wanting an end to arbitrary decisions made by elected officials."(80) Whether someone was a student of an allegedly impersonal university or a citizen of a rural community, an unresponsive government offended shared values. When Pesonen spoke of subversion of the democratic process, it wasn't necessary to be a college student to know what he meant.

By early 1963, this message of public activism and decentralized decision making espoused by the Association to Preserve Bodega Head drew in a broad array of activists. The movement's organizers ranged from far-right libertarians to former members of the IWW. Through leafleting and door-to-door visits, association activists were able to tap into a general discontent with a local political system that was so secretive that even boards of education held closed meetings. Sonoma State College students held a sympathy march in May to protest the "travesty perpetrated by the supervisors. They called for the "spontaneous thinking and the liberal and individualistic freedom of all mankind." The students wanted each citizen to "have the privilege and also the responsibility to voice his own reasoned opinion in any public matter."(81)

Political considerations alone could not have drawn a majority of the residents to the cause. Many of the local ranchers and farmers were not interested in politics, but were concerned with their health and incomes. Sloan recalls that, while people joined the fight for diverse reasons, safety concerns most worried the general public.

With the grassroots in Sonoma County, safety was clearly the issue. Most people didn't care [about politics]. . . . If you're trying to get people aroused about what is going on . . . you use the most emotional issue you can find.(82)

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/dorissloanbodegabay" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Doris Sloan recalls the campaign against building a nuclear plant in Bodega Bay.

Video: Shaping San Francisco

Fear of radioactive contamination served the association's purposes perfectly. In January 1963 they disseminated an analysis of the growing dangers of technology. Using the "food-chain argument" popularized by Rachel Carson's recent publication of Silent Spring, they warned that cows nearby Bodega could ingest radioactive contamination from grass.(83)

By stressing this argument, the Bodega activists were on the cutting edge of a new phase of the conservation movement that focused on the effects of technology on the environment. The movement prior to the early 1960s had concentrated on making scenic and recreational land available to the public. By the middle of the decade, pollution, pesticides, and food-chain concerns dominated the conservationists' agenda.(84) PG&E officials ridiculed the association's "lack of knowledge plus a deliberate program of misinformation" and maintained that the plant could be built safely under San Francisco's Union Square.(85) These assurances pacified no one in a year when fallout from atmospheric testing peaked. Activists drew a direct correlation between the fallout from weapons and the fallout experienced from peaceful applications.

Radioactive debris from a 1957 reactor accident in Windscale, England, had fallen on the countryside and infected milk supplies. This alerted dairy farmers of Sonoma to the dangers of the atom. Local creameries agreed to foot the association's legal expenses.(86)

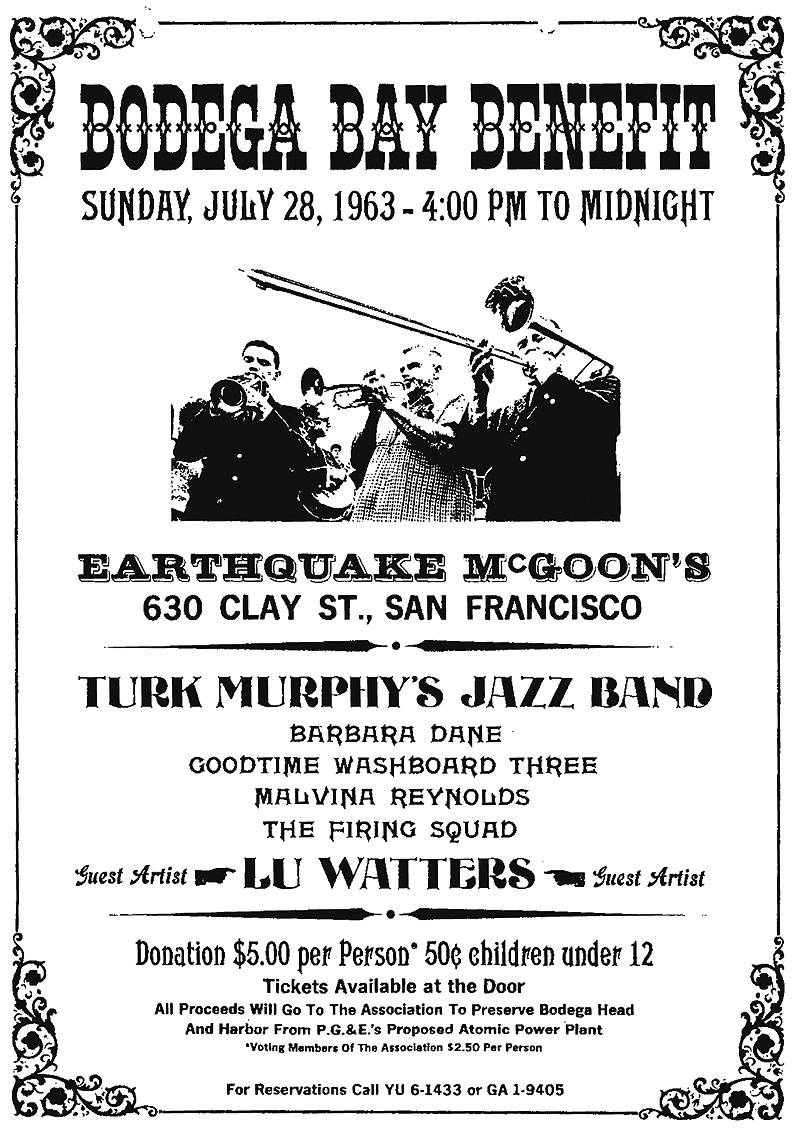

An eight-hour benefit to raise funds for the Association to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor, held at Earthquake McGoon's, featured activist-entertainers such as Turk Murphy, Malvina Reynolds, who contributed new songs to the protest movement, and musician Lu Watters, who came out of retirement to play for the cause.

Photo: Courtesy David Pesonen

The anti-Bodega plant movement also attracted supporters through social activities and atten tion-getting publicity stunts. Pesonen maintained interest in the association through picnics and outdoor parties at Doran Park. Communist folk singer Malvina Reynolds wrote antinuclear pieces for the campaign. Jazz musician Lu Watters took a personal interest in the cause and came out of retirement to play for the association at the San Francisco nightclub, "Earthquake McGoon's." Watters even made a record called "Blues over Bodega." The association pioneered the idea of holding balloon releases at its parties to demonstrate where plant fallout would travel. Years later, antinuclear activists would regularly use these releases to gain media attention.(87) Through these efforts, David Pesonen transformed the association from a disorganized band of a dozen individuals into a force of nearly two thousand members with a budget of ten thousand dollars by the end of 1963.(88)

Despite this success, Pesonen's type of showmanship made even David Brower uncomfortable.(89) It wasindicative of the differences between the two men on how to use citizen activists and just how militant activists should be. Brower was a pluralist who recognized that rising membership allowed the club to enter power politics on a national level; the concept focused on centralized leadership in command of an army of adherents. As Pesonen recognized, the club's internal squabbling and lack of focus made this tactic almost impossible. Pesonen employed the method the New Left would bequeath to the politics of the 1960s and 1970s of creating a single-issue organization that could effectively reach and educate local citizens.(90)

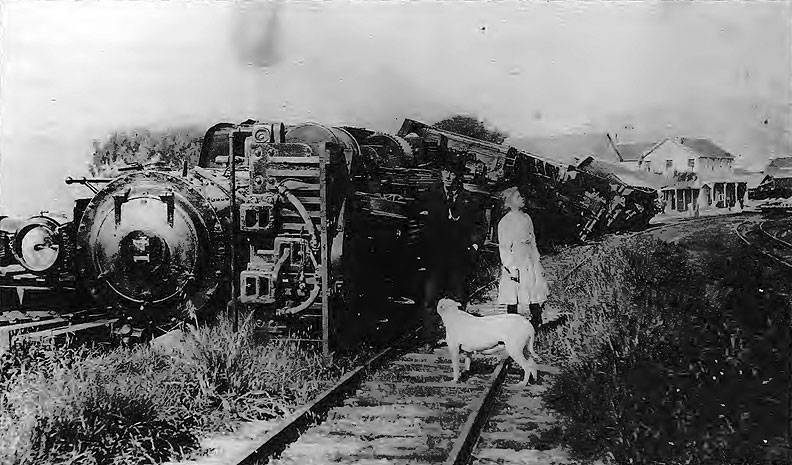

One tactic of activists against the Bodega plant was to play up the dangers that could result from an earthquake. This historic photograph, which they used during the fight, shows a locomotive that capsized at Point Reyes Station, a few miles south of Bodega, during the 1906 quake. In countering such risks, PG&E responded that the train ran on a narrow gauge and was likely to overturn at any small disturbance.

Photo: Courtesy David Pesonen

Such decentralization was the environmental movement's future at the grass-roots level. The Association to Preserve Bodega Head had drifted so far from its original aesthetic roots that some in the group wanted to shed the conservationist label. Pesonen was not unsympathetic, but he realized how much the radicals needed the liberals' respectable image. The association had attracted some communists. Pesonen admitted in private that even the association's lawyer, Benjamin Dreyfus, was "pink" and headed the leftist National Lawyers Guild. J. Edgar Hoover saw the association and student protests as efforts to "discredit [the] government [and] private enterprise," and the FBI tracked their activities.(91) The respectable facade of traditional conservation groups protected Pesonen's group from red-baiting.(92)

The association's success led to feelings of guilt among some Sierra Club members. Director Jules Eichorn found he could no longer defend the board's inaction to club chapters. "This is no longer a local affair," he wrote to Wayburn, "but a national one and we, as the supposed leaders of conservation, are backing down on the very basis for our existence."(93) Some younger men had joined the board in the early 1960s, and they were sympathetic to Brower and as radical as Pesonen. Fred Eissler, an English teacher, was one who was excited by the possibilities of citizen activism and what he considered to be "one of the model conservation campaigns of our day." With other nuclear plant controversies stirring in California, Eissler was exasperated with the club's "intermittent and generally ineffective" support for a burgeoning movement.(94)

The association managed to divide more than the Sierra Club. The issue split politicians along partisan lines throughout the spring and summer of 1963. Karl Kortum's wife Jean spearheaded the anti-plant political lobbying effort and pushed the issue into San Francisco's urban political arena.

Jean Kortum had been active in the New America Democratic Club, which had formed in 1956 to support Adlai Stevenson's presidential bid. Jean organized efforts by a number of San Francisco Democratic clubs, who picketed PG&E's offices, and drew in support from Democratic state and national politicians. Karl Kortum managed to meet personally with Lyndon Johnson's aide, Bill Moyers, and provide him with anti-Bodega literature. Especially damaging to PG&E was Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall's expression of concern for the plant's safety, and his efforts to have the U.S. Geological Survey study the suitability of the power plant's foundation. Udall even visited Bodega Head and met some of the local activists.(95)

At the state level, Jean Kortum persuaded the California Democratic Council to pass a resolution opposing the plant. Governor Edmund Brown declared his opposition, but with the PUC ruling the governor confessed he could do little. Representative Philip Burton introduced legislation asking the Department of the Interior to study the plant site.(96) The Marin Republican Association took the low ground, claiming the opposition was under the influence of Democrats and communists. Most Republicans preferred the more moderate line of California party chairman Casper Weinberger, who ostensibly claimed impartiality in contending that Bodega was "a technical matter for the Atomic Energy Commission and its experts to decide."(97)

The Association to Preserve Bodega Head added fuel to the blazing issue with attacks on PG&E advertising. The group claimed PG&E was spending rate-payer money on political lobby efforts and had shown right-wing films to its employees.

This type of political controversy was what the AEC wanted to avoid for its fledgling nuclear program. AEC Commissioner Glenn Seaberg had declared early in 1963 that the nuclear power program had "gone critical" and was on the threshold of economic competitiveness.(98) But now the program appeared to be bogging down in opposition on many fronts. Residents in Malibu who feared growth and overdevelopment fought a plant proposal there, in what appeared to be a Bodega-inspired movement. The Ravenswood reactor in Queens, just across the East River from Manhattan, had also run into insurmountable resistance because of its proximity to ten million residents.

The Bodega Head plant received its death blow in August 1963, at the hands of Pesonen's association. Pesonen hired geologist Pierre Saint-Amand to consult the organization on the suitability of the excavated site at Bodega, which lay perilously close to the San Andreas Fault system. As Doris Sloan recalls "it was one of the high points of my life" when she escorted the geologist to Bodega Head on a cold rainy day. "I couldn't believe my eyes . . . we came around the corner and the gate was open and there was no PG&E person in the little gate-house to keep you from walking in." As the two slogged through the mud toward the empty site, Saint-Amand exclaimed '"ooh' and.. . 'ah'," as his eyes came to rest on a "spectacular"earthquake fault slicing through the excavation.(99) At a press conference, Amand described the fault and the heavily fractured nature of the site, which, in his opinion, was sufficient cause to abandon the project. "A worse foundation condition," Amand concluded, "would be difficult to envision."(100)

At this juncture, Stewart Udall's influence proved crucial in affecting the AEC's decision. The Department of the Interior's U.S. Geological Survey soon followed with its own inspection results, which declared the site unsuitable because of auxiliary faults. Survey spokesman J.P. Eaton declared that "acceptance of the Bodega Head as a safe reactor site will establish a precedent that will make it exceedingly difficult to reject any proposed future site on the grounds of extreme earthquake risk."(101)

PG&E had no intention of surrendering, however. Its staff considered Eaton to be little more than Stewart Udall's "hatchet man" and brought out their own expert, who declared that the site had not been active for over forty thousand years.(102) PG&E modified its construction plan in April to accommodate any possible shifting. PG&E con cluded that "the possibility [of a site-damaging quake] is so remote that for all practical purposes it may be disregarded."(103) Pesonen retaliated that the only experts who were not concerned with the fault were on the utility payroll.(104) PG&E also sought to undermine the notion that Bodega was a scenic area. They brought pronuclear congressman Craig Hosmer to visit. He declared that Bodega Head was a barren, brown, wind swept piece of property without any charm, and will be improved if a power plant is built there."(105) But debates on aesthetics no longer mattered. The safety issue, it appeared, would now determine the plant's fate.

The end was fast approaching. PG&E suspended construction in October 1963, when the fault controversy erupted. As Pesonen's association celebrated in October 1964 its first annual "Empty Hole in the Head Day," the AEC released four separate reports from various government bureaus, three of which found the site unsuitable. Even the AEC staff recommended against construction.

The staff concluded that PG&E's new design was untried and could not provide reasonable assurance against earthquake hazards.(106) The utility took Pesonen's advice to "bow out gracefully" and cancelled construction on October 30, 1964.(107) The Sierra Club's president, Will Siri, praised the utility's "public spirited" decision and called for the establishment of a state park at the site.(108)

The political fallout from the Bodega Head controversy spread over the landscape. Legislators debated why the system had failed to act decisively in the incident, and state agencies drew up plans to consider how siting controversies could be handled in the future in a way that would consider scenic values. By revealing differences among experts, the uproar contributed to the loss of faith in technical elites and government generally. Editorialists admitted that perhaps it was not so wrong for "genuinely concerned people to question. . . [atomic power] even when given assurances that everything is 'perfectly safe."'(109) Sonoma Valley residents formed the Valley of the Moon, Inc. to "enable the citizens of the valley . . . to participate more actively in its development" and to watch with a distrustful eye over the activities of the supervisors.(110) Although he once speculated that existing institutions could not be reformed, Pesonen's activism had succeeded in making the state government somewhat more responsive to its citizens and citizens more committed to politics. In the residents' fight to maintain their way of life, the Bodega Bay community changed. A quick stroll around the village today reveals a number of real estate developments and vacation homes. Hazel Mitchell and others recognized that their political impotence and isolation had made them an easy target for development; that isolation had to end. To provide a viable alternative to industrialization, the Bodega Bay Chamber of Commerce actively promoted Bodega Head's beauty into what has become a substantial tourist trade.(111)

It was possible to think that this political transformation was spreading. On the heels of the association's victory, the Berkeley campus that David Pesonen considered impervious to social change was in the throes of the Free Speech Movement. Student and professor alike seemed ready to lead social change. Cheered by the support of the Academic Senate for the student demonstrations, Pesonen believed that the professors were shedding their fear of intimidation. In a letter, he expressed his confidence that "if the present sense of freedom and dignity in the faculty can be sustained," protection of Bodega Head was assured.(112) But the faculty and the association's leader were less radical than the heady days of 1964 might have suggested. There was an important difference between political tolerance—the central issue in the Free Speech Movement—and activism; the faculty could not unite to become the community's conscience. Similarly, Pesonen was no radical. The young "anarchist" eventually returned to school and became a lawyer, but he remained active in antinuclear battles in the 1970s.

The victory was less heartening for the Sierra Club. Militants within the organization felt vindicated, while conservatives were horrified and considered the entire episode a "tragedy."(113) Fred Eissler and Will Siri emerged as the principal antagonists in the debate over nuclear policy and safety, and would clash repeatedly on the same question in the future. Because of the split, the dub could do no more than declare its neutrality on the growing safety debate.(114) After Bodega, board member Eissler pushed the club to raise questions of safety against nuclear power. But as president, Siri represented the club as still being in favor of plants located along the Pacific Coast.(115) Members were generally unconcerned with safety issues and even favored atomic plants in highly developed locations to avoid power facilities in wilderness areas.(116)

Growth and wilderness preservation remained their central focus. But these concerns were too limited to encompass the complex nuclear issues of the 1960s and 1970s. The safety of reactors and waste would dominate the nuclear question in the decades to come.

The 1960s were a dangerous time for the Sierra Club to be a house divided. Despite its ambivalent role, the Bodega controversy had increased the Sierra Club's power. Because of the Bodega Head fiasco, PG&E had little stomach to face conservation forces a second time and later in the 1960s sought negotiations with the club on the utility's proposed Diablo Canyon nuclear plant. By then, the cleavages resulting from the Bodega debate had widened dramatically, and the position the club arrived at—not to oppose the Diablo plant—tore the organization apart. Because the internal dispute involved other issues, not the least of which were finances and David Brower's leadership, his ouster masked the long-term ideological victory of the radicals. By the 1970s, the club adopted vigorous positions on population, nuclear power, and political lobbying.(117)

The changes wrought in the 1960s were also structural, and here Bodega foreshadowed the decentralization of club authority. While some dismiss the New Left of the 1960s and its accomplishments, single-issue activism has come to dominate the political landscape. Historians consider the environmental movement to be palpable evidence of a resurgent desire for participatory democracy.(118) Bodega was a precursor of this trend.

NOTES

The author would like to thank Richard Abrams, James Gregory, and Carolyn Merchant for commenting on earlier versions of this article. The author also thanks David Pesonen, Magrita Klassen, Hazel Mitchell, Joel Hedgpeth, Karl Kortum, and Doris Sloan for providing interviews, information, and photos for this article.

1. Ralph I. Smith to Dr. Edgar Wayburn, 26 April 1958, Sierra Club San Francisco Bay Chapter Archives, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley (hereinafter cited as Bay Chapter Archives), carton 30.

2. Richard M. Leonard, "Mountaineer, Law yer, Environmentalist," interview conducted by Susan R. Schrepfer, Bancroft Library, Regional Oral History Office,1975, 161.

3. David Pesonen to Dr. Edgar Wayburn, 26 September 1963, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30.

4. Etahn M. Cohen, Ideology, Interest Group Formation, and the New Left (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1988), 3-4.

5. J. Samuel Walker, "Reactor at the Fault: The Bodega Bay Nuclear Plant Controversy, 1958-1964-A Case Study in the Politics of Technology," Pacific Historical Review 59 (1990):323-348; Dorothy Nelkin, Nuclear Power and its Critics (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1971), 9-10; Gerald H. Clarfield and William M. Wiecek, Nuclear America (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 355-56; Sheldon Novick, The Careless Atom (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1969), 34-50. For works that recognize the political aspects of the controversy, see Richard L. Meehan, The Atom and the Fault (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1984), 1-20; and Brian Balogh, Chain Reaction: Expert Debate and Public Participation in American Commercial Nuclear Power (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

6. Edgar Wayburn, interview by author, tape recording, San Francisco, 27 March 1990. For a study of Bodega Head's ecosystems see Michael G. Barbour, Coastal Ecology Bodega Head (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973).

7. David R. Brower to Joseph R. Knowland, 20 August 1958, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30.

8. J.W. Hedgpeth to R.E. Burns, 20 September 1958, Joel Hedgpeth Files, Bancroft Library (hereinafter cited as Hedgpeth Files), box 1.

9. Edgar Wayburn, interview by author, 27 March 1990; Edgar Wayburn, "Sierra Club Statesman, Leader of the Parks and Wilderness Movement," interview by Ann Lage and Susan Schrepfer, 1976-81, 59, Bancroft Library.

10. Michael Cohen, The History of the Sierra Club,1892-1970 (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1988), 89.

11. Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, California), 15 January 1960, 12 (hereinafter cited as SRPD).

12. David E. Pesonen, "A Visit to an Atomic Park," (by the author, 1962), Bancroft Library, 8.

13. Pesonen, "Atomic Park," 13.

14. This use permit authorized the construction of power lines through Doran Park. In February 1960, the supervisors issued a second use permit for installation of the power plant. Pesonen, "Atomic Park," 13-15.

15. Ibid., 9.

16. J.W. Hedgpeth to George Dusheck, 21 September 1958, Hedgpeth Files, box 1.

17. Clem Miller to Joel W. Hedgpeth, 30 April 1959, Hedgpeth Files, box 1.

18. Hazel Mitchell, interview by author, tape recording, Bodega Bay, 7 July 1991.

19. The University of California also represented a potential ally in the fight. The university expressed interest in Bodega as a marine research station. In November 1957, six months before PG&E publicly admitted its stake in Bodega, the university withdrew. Berkeley Chancellor Clark Kerr claimed that the university's desire to locate the station at Bodega was only the expressed opinion of some faculty members. Hedgpeth knew Bodega had been the prime site in the university's plans and suspected that official vacillation was due to the fact that PG&E's "tentacles go deeply into the University." San Francisco News, 12 September 1958, 1; J.W. Hedgpeth to Geo[rge] Dusheck, 21 September 1958, Hedgpeth Files, box 1.

20. Peggy and Edgar Wayburn, "Our Vanishing Wilderness," Sierra Club Bulletin (hereinafter cited as SCB) 42 (January 1957): 9.

21. Samuel H. Ordway, Jr., Resources and the American Dream (New York: Ronald Press Co.,1953); Fairfield Osborn, Our Plundered Planet (New York: Little, Brown, & Co., 1948); and Harrison Brown, The Challenge of Man's Future (New York: The Viking Press, 1954).

22. David Brower, "The Sierra Club on the National Scene," SCB 41 (January 1956).

23. David R. Brower, Diary, 15 November 1960, David Brower Papers, Bancroft Library, carton 5.

24. See graph in Sierra Club Archives, carton 203; David R. Brower, "Scenic Resources for the Future," SCB 41(December 1956):2.

25. David R. Brower, Diary, 15 March 1961, David Brower Papers, carton 5.

26. David R. Brower, "Wilderness-Conflict and Conscience," SCB 42 (June 1957):5, 4, 10.

27. "The Fifth Biennial Wilderness Conference," SCB 42 (June 1957): 82.

28. David Brower, "How Effective is the Conservation Force?" SCB46 (March 1961): 2.

29. Meeting Minutes, Board of Directors, 5 December 1959, Sierra Club Archives (hereinafter cited as Minutes).

30. David R. Brower, Diary, 15 November 1960, David Brower Papers, carton 5.

31. Phillip S. Flint to Glenn Seaborg and Edmund Brown, 3 December 1960, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30.

32. Lewis F.Clark to Edgar Wayburn, 3 February 1961, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30.

33. Everett McKeage to Edgar Wayburn, 15 June 1961, Sierra Club Archives, carton 120.

34. Gerald H. Garfield and William M.Wiecek, Nuclear America (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 276.

35. George T. Mazuzan and J. Samuel Walker, Controlling the Atom: The Beginnings of Nuclear Regulation, 1946-1962 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 147.

36. Central Surveys, Inc., Nationwide Public Opinion Survey (Shenandoah, Iowa: Central Surveys, Inc., 1967), 22.

37. Joel Hedgpeth to the Public Utilities Commission, 14 March 1962, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30.

38. David Pesonen, interview by author, tape recording, Oakland, California, 5 March 1990.

39. The Chronicle (San Francisco, hereinafter cited as SFC), 14 March 1962, 34.

40. Pesonen, "Atomic Park," 22.

41. Ibid., 27.

42. SRPD, 10 June 1962, 10.

43. Ibid., 6 June 1962, 1.

44. Berry and Pesonen believed the utility and the AEC had pressured the university to accommodate the plant and that the university was, in tum, preventing the faculty from speaking out against the plant. Their suspicions were reinforced by the fact that Chancellor Glenn Seaborg had been named commissioner of the AEC following John F. Kennedy's election as president of the United States. The university's spokesman maintained the plant would pose no harm to the marine station. This flew in the face of faculty reports that urged the university to oppose plant construction because of the hazard it posed; Phillip S. Berry to Mr. Leonard, 26 September 1962, Sierra Club Archives, carton 143.

45. Richard M. Leonard, "Mountaineer," 431.

46. David R. Brower, "Environmental Activist, Publicist and Prophet," interview by Susan Schrepfer,1974-78, Bancroft Library, 198-99.

47. Minutes, 14 October 1962, Sierra Club Archives.

48. Phillip Berry to Mr. Leonard, 26 September 1962, Sierra Club Archives, carton 143.

49. Richard M. Leonard to Phillip S. Berry, 8 October 1962, Sierra Club Archives, carton 129.

50. Minutes, 7 September 1963, Sierra Club Archives.

51. Pesonen, interview.

52. David E. Pesonen to James B. Muldoon, 24 December 1962, Hedgpeth Files, box1.

53. Dave [Pesonen] to Joel [Hedgpeth], 2 December 1962, Hedgpeth Files, box 1.

54. David E. Pesonen, "Outdoor Recreation for America," SCB 47 (May 1962): 8.

55. David Pesonen to Edgar Waybum, 26 September 1963, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30.

56. David E. Pesonen to James B. Muldoon, 24 December 1962, Hedgpeth Files, box 1.

57. Pesonen, "Atomic Park," 30, 31. 58. Ibid., 38.

59. SRPD, 19 March 1963, 7; SRPD, 21 May 1963, 6.

60. Argus-Courier (Petaluma, California), 15 May 1963.

61. James M. Miller to R.J. Stull, 15 November 1957, University of California Archives, Bancroft Library, CU-149, box 45.

62. For a complete overview, see University of California Archives, CU-149, box 45, file:8, especially J.D. Frauchy and D.L. Inman to Roger Stainer,14 June 1960; James Moulton to Glenn T. Seaborg, 1 August 1960;Thomas Cunningham to Glenn T. Seaborg, 23 August 1960.

63. Pesonen, interview.

64. David Brower to Each Member of the Executive Committee, 7 November 1962, Sierra Club Archives, carton 129.

65. Harold [Bradley] to Dave [Brower], 8 January 1963, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30.

66. David Brower to Harold Bradley, 9 January 1963, Bay Chapter Archives,carton 30.

67. Harold Bradley to David Brower, 10 January1963, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30.

68. Dave Pesonen to Joel [Hedgpeth], 25 November 1962, Hedgpeth Files, box 1.

69. Susan Schrepfer, The Fight to Save the Redwoods (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983), 174.

70. Speech by D.B. Luten, "A Geographer Looks at the Future of Sonoma County," 10 November 1962, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30, 2.

71. Speech [David Pesonen, 10 November 1962], Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30, 4.

72. Luten, "Future of Sonoma," 4.

73. Doris Sloan, interview by author, tape recording, Berkeley, California, 30 April 1990; Joel Hedgpeth to William C. Bricca, 20 November 1962, Hedgpeth Files, box 1.

74. Speech [David Pesonen, 10 November 1962], 7.

75. SFC, 10 November 1962, 1.

76. SFC, 1 December 1962, 44; SRPD, 12 December 1962, 1; SRPD,15 January 1963, 9.

77. Dave Pesonen to Joel [Hedgpeth], 25 November 1962, Hedgpeth Files, box 1.

78. SFC, 17 April 1963, 1.

79. The Times (Guerneville, CA), 22May 1963, 1.

80. Sloan, interview.

81. Argus-Courier (Petaluma ,CA), 9 April 1963.

82. Sloan, interview.

83. Northern California Association to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor, "The Problems of Industrial Fallout: A Brief Review," 3 January 1963, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30.

84. Samuel Hays, Beauty, Health and Permanence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 28, 54.

85. Index-Tribune (Sonoma County, CA), 11 April 1963, 3; New York Times (West), 28 February 1963, 3.

86. [Joel Hedgpeth] to Jack [Spencer], 26 March 1963, Hedgpeth Files, box 1. The farm community was already sensitive to any appearance of contamination of food through pesticides and radioactive fallout. See "Dairymen Take Action Against Fallout," Farm Journal 86 (October,1962):31, 64; and "You're Accused of Poisoning Food," Farm Journal 86 (September, 1962):29,52.

87. Sloan, interview.

88. Northern California Association to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor, Newsletter 9 (9 January 1964):2, 3; Magrita Klassen, interview by author, tape recording, Sonoma, California, 1 July 1991; Doris Sloan, interview; David Pesonen to John Lear, 30 September 1963, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30.

89. Brower, "Environmental Activist," 198.

90. Earlier citizen activism had focused on broad issues when organizing on a community level. See Saul Alinsky, Reveille for Radicals (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1945), 80-81.

91. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, San Francisco Division, Central Records, "Northern California Association to Preserve Bodega Head and Harbor," 1990, File no. 190-SF-91003.

92. D[avid Pesonen) to Joel [Hedgpeth), 20 December 1962, Hedgpeth Files, box 1.

93. Jules M. Eichorn to Edgar Waybum, 14 May 1963, Sierra Club Archives, carton 120.

94. Fred Eissler to David Brower, 31 July 1963, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30.

95. Jean Kortum, interview by author, transcript of telephone conversation, 17 April 1992; Walker, "Reactor at the Fault,"335; and Hazel Mitchell, interview.

96. Argus-Courier, 13 May 1963, 1;SFC,18 July 1963, 7.

97. SFC, 8 August 1963, 4; SFC, 23 August 1963.

98. NYT (West), 21 February 1963, 1.

99. West Sonoma County Paper, 1-7 October1987, 7; SRPD, 29 August 1963, 1.

100. SRPD, 29 August 1963, 1.

101. San Francisco News-Call Bulletin, 4 October 1963, 1; Walker, "Reactor at the Fault," 335, 337-41.

102. Meehan, The Atom and the Fault, 13.

103. SFC, 7 May 1964, 2.

104. Oakland Tribune, 28 January 1964; SFC, 30 January 1964.

105. SFC, 14 September 1963, 7.

106. Walker, "Reactor at the Fault," 343.

107. The Sacramento Bee, 28 October 1964, 2.

108. Sierra Club, Press Release, 31 October 1964, Bay Chapter Archives, carton 30.

109. Index-Tribune, 12 November 1964, sec. 4-2.

110. SRPD, 18 June 1964, 6.

111. Hazel Mitchell, interview.

112. David E. Pesonen to Friend of Bodega Bay, 14 December 1964, Sierra Club Archives, carton 165.

113. Doris [Leonard) to Will [Siri], 7 April 1966, Sierra Club Archives, carton 165.

114. Minutes, 7 May 1966, Sierra Club Archives.

115. William E. Siri to Hugo Fisher, 8 December 1964, Sierra Club Archives, carton 165.

116. SFC, 3 April 1965, 1.

117. For a study of the shift in the Sierra Club's position on nuclear power, see Brock Evans, "Sierra Club Involvement in Nuclear Power: An Evolution of Awareness," Oregon Law Review 54 (1975): 607-21.

118. Hays, Beauty; Cohen, History of the Sierra Club, 457.